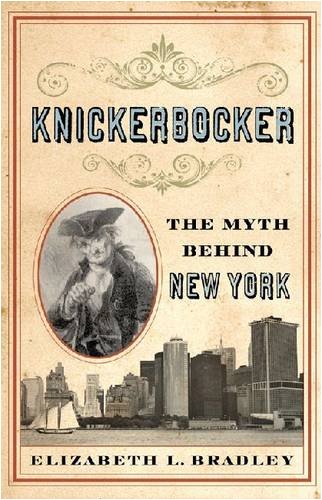

New Yorkers encounter the peculiar, comic-sounding word knickerbocker all over the city: on street signs and at subway stops, in the names of condominiums, restaurants, and bars, and—shortened to the catchier Knicks—on basketball jerseys. When consummate man-about-town George Plimpton died in 2003, the New York Observer called him “the last Knickerbocker.” But what is a knickerbocker? Is being called one praise or a curse? According to historian Elizabeth L. Bradley’s new study, the term has been “used alternately with reverence or disdain” over its two-hundred-year history, quickly slipping its original meaning to become a “link between a strange, sometimes unholy assemblage of New Yorkers.”

The story begins with Washington Irving’s 1809 A History of New York, from the Beginning of the World to the End of the Dutch Dynasty, a long-winded mock history, narrated by a fictional curmudgeon named Diedrich Knickerbocker. Looking to boost the credibility of the book’s incredible narrator, Irving included an introduction by Knickerbocker’s landlord (a literary device later exploited memorably in Hesse’s Steppenwolf) and placed hoax ads in city newspapers. Knickerbocker’s first public appearance was in the Evening Post, in which the landlord described his tenant as “a small elderly gentleman, dressed in an old black coat and cocked hat,” who had left the hotel without paying. The landlord, anxious to receive the rent he was owed, placed the notice, which continued, “As there are some reasons for believing [Knickerbocker] is not entirely in his right mind . . . any information concerning him . . . will be thankfully received.” Similar notices appeared in the following weeks, until the landlord finally announced that he would be forced to publish the manuscript found in Knickerbocker’s room “in order to discharge certain debts he has left behind.”

Like his creator, Knickerbocker was sly, wise, and prone to fibbing. Indeed, part of the book’s charm is its whimsical blend of fact and fiction. But Knickerbocker’s most endearing trait is his charismatic mix of “enthusiasm, self-aggrandizement, and irony,” a “combination of wonder and weariness” that is “the ideal register in which to write and talk about” New York. Though intended as a humorous character, Knickerbocker was adopted in earnest by the city’s denizens and was the amiable originator of the “New York Story” genre, “the first to awaken New Yorkers to a consciousness of their trademark exceptionalism.”

Bradley creates an engaging account of the city through the fictional Knickerbocker, who was a steady presence “over two centuries of wrenching urban transformation, from the post-colonial to the postmodern.” Knickerbocker’s name, likeness, and, most important, his attitude quickly became ubiquitous and were enlisted to serve “a host of political, commercial, and social agendas.” Throughout the nineteenth century, especially during the Gilded Age in New York City, Knickerbocker was “shorthand for ‘elite and white,’” an invocation of old money and an aristocratic ideal meant to further class- and race-based distinctions. By the dawn of the twentieth century, he was an all-purpose icon that signified New York in general, especially “its inimitable, cosmopolitan allure,” granting whoever drafted Knickerbocker to their cause an “authentic” New York City pedigree: glamorous, wry, and a bit self-important.

Bradley is a perceptive and lively writer and does a superb job of tracing the many strands of the Knickerbocker myth. She provides the historical context necessary to illustrate the ways the Knickerbocker brand was invoked and provides deft analysis of the cultural meanings it accrued. “The image of the Knickerbocker—shabby and superior, ironic and intellectual” is still relevant and descriptive of contemporary New York, she argues, and “taking Irving’s creation as their inspiration [New Yorkers] should seek out and celebrate their city’s patchwork, ambivalent, multiethnic heritage, with all the risk and freedom for the future that it implies.”

The abruptly clipped word Knicks is the most widely known reference to the myth today (the team’s owners shortened the name and retired its old logo, a cartoonish drawing of Deidrich dribbling a basketball, in 1964). Bradley writes that, during the Knicks’ heyday in the ’60s, “the Knickerbocker name was once again shorthand for world-class style and for success.” And today? Knicks has become synonymous with egregious losing. Perhaps the team’s luck would change if they ditched their bland basketball logo and revived the image of their sassy namesake.

David O’Neill is Bookforum's editorial assistant.