Though these stories begin with a Kasbah gossip, sharp of eye and tongue, and end with the towering rages of an Arab patriarch, The Clash of Images feels remarkably like good news. The first American publication of Abdelfattah Kilito’s fiction presents a Muslim world in the process of transformation, in a North African seaport still under French rule; it reveals how that culture out of the North, embodied in everything from French schooling to Tintin comics, swept away habits of thought that had sustained the Arab Old City for centuries. Yet the mood would never be termed angry, but rather elegiac, even fond. It’s a Clash without clashes, its anecdotes and meditations free of outrage.

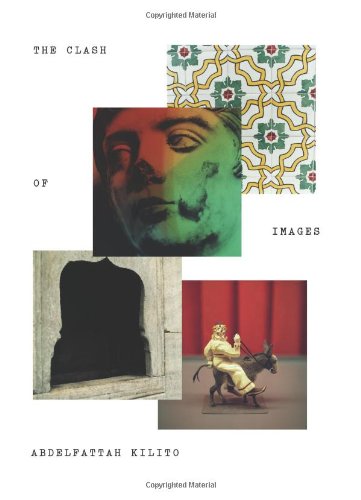

The pieces in Clash all pretend to reminiscence, and seem to have some basis in Kilito’s experience. Born in Rabat, Morocco, at the end of the last World War, Kilito had a European education and published a good deal of criticism, while teaching at places like the Sorbonne and Harvard. Thus while this new fiction (he has two previous, in French) can be read as a coming-of-age story, the book is more an investigation of ideas. The text opens with an author’s note that lays out his philosophic purpose, namely, examining a crucial distinction between the cultures south and north of the Mediterranean. Unlike in Christian Europe, the note explains, Islam had a culture “without the image,” by which Kilito means images of the human figure. He acknowledges the Arab history of painting, but insists, “it didn’t occur to anyone to have their portrait made. Our ancestors were faceless.”

This resistance to representation has roots in the Quran, but over the past centuries was vanquished by European influence, nothing if not friendly to the human image. So too, the narrator of most of these thirteen stories, a boy first seen as a child and then as an adolescent, can’t resist the “scandalous” spell of “photography, the cinema, comic strips, and illustrated books.”

The first piece is without this protagonist, named Abdallah—and the boy’s earliest memories recall a milieu that depends wholly on talk, both the gossip of the neighborhood and the words of the Prophet. But by the third story, Abdallah and his peers are ready to renounce the way of life taught in the msid, the religious school, a way defined by the Quran, which must be memorized in order “to hold it in one’s body, to make it a piece of one’s life.” This “Revolt in the Msid,” proves significant also as the first story that Abdallah narrates. In later pieces, when he details the impact of the novel Treasure Island, of comic books, camp sing-alongs, and Grade-B Westerns, the conflicts and discoveries will feel familiar to anyone ravished by Euro-American entertainment culture, as it rampaged throughout the world over the last fifty years or so.

What distinguishes Kilito’s rendering of old ways yielding to new is its humanity, forever forging links between a faith-based childhood and a skeptical European adulthood. Thus the longest, funniest story, “Cinédays,” at the book’s climax, ends with a resonant image depicting how it feels to have a movie break down in mid-reel:

The spectators . . . wanted to go back to sleep and rejoin the sweet dream that was now going up in smoke. In the cave whose lights had just come on they were freed of their chains, yet they wanted nothing more than to put the chains back on, to . . . let their gazes glide over those fleeting, illusory, and deceitful images.

So Plato’s Cave comes to the medina’s grind house. That this volume makes the relocation work is, among other things, a testimony to Robyn Creswell’s translation; the three English adjectives that close the passage above, for instance, collaborate without overlapping. The collaboration that matters most, however, takes place in Kilito’s imagination, where the divergent cultures of the South and North construct a unique variation of the Bildungsroman, one more open than most to myth and parable. That openness has its risks; it can weigh down the smallest detail with implication, as in the story “A Season in the Hammam,” which clogs a public bathhouse with signifiers. But then again, “A Season” is one of the last of these stories, and so its myth-mongering is perhaps indicative of the hero’s last stage of growth: a return to his home ground.

In the closing story, “The Blooming Garden,” Abdallah comes back to the Kasbah as an adult and can no longer find his way around. Formerly his whole world, this urban jumble now seems “the remnants of a campsite abandoned in the middle of the desert.” Yet rather than leaving him crushed, this vision of lost childhood sets him thinking of the poetry that used be sung around such campfires, a poetry of heroes and adventures, ignoring religion in favor of what the Prophet called “lying.” After that, with fitting perversity, the book ends by combining image and lie in an act of love. The returning prodigal recalls how his grandmother used to sew up broken flower-stems in the family garden, in order to fool his grandfather, who loved his roses so fiercely he would fly into a rage whenever one was lost. Kilito at his best makes the Image welcome even in the timeless homeland of the Word.

John Domini’s most recent novel is A Tomb on the Periphery (Gival Press, 2008). A selection of his essays, fiction, and poetry are at johndomini.com.