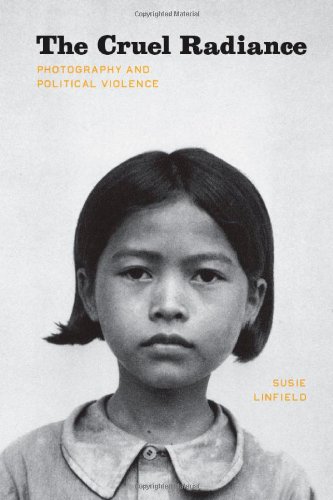

The girl in the photograph wears her black hair tucked behind her ears. Her part is slightly crooked, and there is a small mole low on her throat, right above the top button of her blouse. She might be anywhere between five and ten years old. She’s been posed against a wall or a screen. Stripped of its context, this is a lovely but unremarkable portrait of a small, serious looking girl, an image that's easy to look at and easy to forget.

But let’s restore the context and look again. Pol Pot liked to have his prisoners photographed. Like the fourteen thousand or so others imprisoned at Tuol Sleng, the Khmer Rouge’s “torture center,” this girl slept shackled to the floor or wall, was likely tortured, photographed, and eventually shot—or bludgeoned to death, if the price of ammunition was high that year.

Is there a “right” way to respond—intellectually, emotionally, aesthetically—to such an image? Do we honor her by looking at her photograph or by refusing to? If we look, can we learn anything about how she lived and why she died? What if we can’t help but notice her beauty—or worse, the inadvertent beauty of the snapshot itself? What does that say about us—or photography? Are these considerations offensive: Do we have a right to make sophistries out of real suffering?

Susie Linfield has written a brave and unsettling book about these questions, and she creates a calculus for a new kind of photography criticism—one that respects photography rather than distrusts it, derives its power from intellect and feeling.

Standing in her way, however, is a tradition of photography critics who have found inherent problems with the medium. Photography has been accused of, briefly, celebrating the status quo and serving as capitalism’s lackey (Bertolt Brecht); creating an “aesthetized” society (Walter Benjamin); appealing to our emotions not our intellect and thus eliciting base reactions (Siegfried Kracauer); manipulating us to produce a desired response (Roland Barthes); inuring us to suffering and deadening the conscience (Susan Sontag); promoting paralysis instead of outrage and action (John Berger); presenting scenes sans context and chronology (Brecht, Sontag) and thus, breeding distortions (Philip Gourevitch, Errol Morris, all of the above).

Into this fray marches Linfield at full tilt, seeking for photography critics “the same freedom of response” enjoyed by critics of film, dance, theater, and music. She defangs the denunciations, neatly explaining that the Frankfurt School’s distrust of photography came out of their particular context: Grossly distorted propaganda photos were used to stoke political hysteria in the already hysterical Weimer Germany—hence Brecht, Benjamin, and Kracauer developed a healthy skepticism. But above all, the book addresses Susan Sontag, for it was Sontag’s On Photography, Linfield writes, that was “responsible for establishing a tone of suspicion and distrust in photography criticism, and for teaching us that to be smart about photographs means to disparage them.”

Where On Photography is blunt, bold, and epigrammatic (recall those lines that land like jabs: “The act of taking pictures is a semblance of appropriation, a semblance of rape”), The Cruel Radiance is on a larger and messier mission. Linfield, who possesses none of Sontag’s theatricality on the page, is earnest and her engagement with the photographs is raw, her belief in photography’s power is absolute. She argues that photographs, more than any other kind of journalism, bring us close to suffering and allow us to feel it quickly and keenly. They make atrocities specific. It’s not enough for us to know that out of the Cambodian genocide, fourteen thousand people were exterminated at one of the Khmer Rouge’s countless camps—it’s the girl with the crooked part in her hair, whose singularity we noticed, whom we will remember, whom we might choose to mourn.

Taking the film critic Pauline Kael as a model of the kind of critical sensibility photography demands, Linfield allows her enthusiasms and prejudices to suffuse the book. The effect can be intimate and instructive—her readings of the images themselves are small miracles of sensitivity and austere beauty—but it can be equally embarrassing, especially when Linfield stoops to ethnocentrism: “The burqa is a grotesque, indeed totalitarian garment.” Capa’s photos of demonstrations “are a pleasure to look at, for the marchers carry portraits of Zola, Voltaire, Diderot, and Gorky rather than of brooding old ayatollahs or teenaged suicides.”

She takes the reader through four historical moments—the Holocaust, the Cultural Revolution, the civil war in Sierra Leone, and the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq—revealing how these different conflicts produced different styles of depiction (Abu Ghraib, for example, seems to have summoned a new era where violence is performed for the camera). She introduces us to three masters—Robert Capa, chronicler of the Spanish Civil War, and contemporary photojournalists James Nachtwey and Gilles Peress—to examine how photographic technique can transmit political philosophy.

Witness the humanist Capa, whose narrative-rich photos feature hardships, certainly, but side by side with nobility, endurance, and dignity. Linfield writes, “Capa gave us pictures of a broken world but he never suggested that destruction is our natural state.” Compare him with Nachtwey, the lugubrious, latter-day Goya, in whose painfully explicit pictures, victims of famine, AIDS, or the machete are so brutalized that they’re barely recognizably human. His photographs don’t invite compassion, solidarity, or recognition: “In showing us the many ways that the human body can be destroyed, Nachtwey can inspire revulsion more easily than empathy.” His images are meant to shock, but at the same time, their formal compositions and classical allusions make them stately lamentations.

Despite its canny organization, the book wants greater internal clarity and consistency. Linfield defends graphic images (such as Nachtwey’s), writing, “Why is the teller, rather than the tale, considered obscene—and in any case, aren’t some of the world’s obscenities worthy of our attention?” But in another part of the book, she lambastes the “Arab press” for showing pictures of people maimed and murdered at the hands of terrorists or American and Israeli soldiers. She turns priggish and excoriates Al-Jazeera for televising “wanton loops of violence.” Describing the images of dying children printed in the Palestinian newspaper Al-Ayyam, she is almost cruel: “These images seem to hail rather than protest the agony of victimization: It’s hard to imagine that they deepened anyone’s thinking.”

Why are these depictions of deaths, as Linfield describes them, “lurid” not “tragic”? How can a newspaper photo “hail” the death of children? Why aren’t these the “right” kinds of photographs, the way, say, Peress’s portraits are? If the distinctions are apparent to Linfield, she doesn’t make them sufficiently clear to the reader, who might be left supposing the author believes that some photographs—or victims—seem more deserving of our attention or compassion than others, an unfortunate prospect for such a bighearted book.

Still, Linfield’s quest is heroic, and if she stumbles, it’s in the pursuit of a powerful—and personal—vision of photography’s necessity and potential. Like Robert Capa, she wants to connect the viewer to causes “out of respect, solidarity, and self-interest rather than pity or guilt.” Like Gilles Peress, she proceeds with a lack of sentimentality and a sensualist’s pleasure in the surprising detail. And like James Nachtwey, she accepts that there is no logic that can explain, no redemption that awaits so much suffering—but still, she bears unflinching witness.

Parul Sehgal is a nonfiction editor at Publishers Weekly.