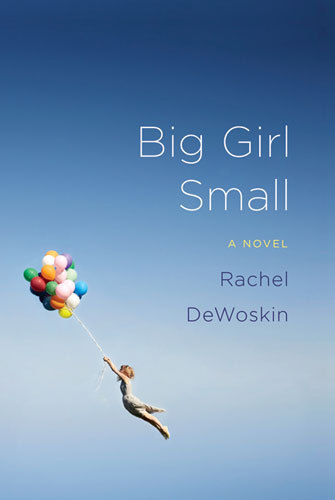

At the start of Big Girl Small, the sixteen-year-old narrator, Judy Lohden, makes an appealing first impression as a wry, snarky translator of teenage mores. Judy is an outsider at her school, and not only by virtue of being the new girl in class: She’s a little person, three-foot-nine-inches tall with “disproportionate” limbs, and her marginal status seems at first to impart the critical distance that gives rise to insight.

This promise, however, is short-lived. “What good is there in seeing your situation clearly if there’s no escape from it?” she asks rhetorically at the end of the first chapter. Of course, seeing clearly is often one’s best hope of escape; by dismissing this power, she is asking for trouble. Judy turns out to be wrong about most things and wise about precious little, which does not necessarily have to be a flaw: The best limited- or compromised-viewpoint narrators manage to occasion new languages, as the five-year-old storyteller of Emma Donoghue’s novel Room did so memorably. But as Judy’s quest for popularity progresses, her story turns into a close-in monologue of boy-crazy adolescence, rendered in a voice that is all too well known to anybody who has read a Judy Blume novel. Why do we hear so little about contemporary literary novels that feature tough and knowing teenage girls? Quirky-smart boys clog the pages of top-shelf fiction, from Skippy Dies to The Selected Works of T. S. Spivet, from The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao to Someday This Pain Will Be Useful to You. But order up a thoroughly modern teenage girl these days and you usually get a diminutive mirror gazer whose powers of social observation dissolve instantly when faced with a cute boy’s smile, or the book is branded Young Adult and relegated to the school library.

Rachel DeWoskin subjects Big Girl Small’s young heroine to a gripping and original chain of events that dramatizes timely questions about sex, social maneuvering, and the evergreen topic of teen cruelty; and Judy’s trials unfold as the fulfillment of relentless foreshadowing, imparting a chronicle-of-a-death-foretold pleasure. Yet it’s difficult to muster much sympathy for a tragic heroine who is such middling company.

As the book begins, Judy is starting eleventh grade. Or, rather, she is telling us about the beginning of eleventh grade, from a fleabag motel in Ypsilanti where she is holed up, dodging the ravenous cameras of the nightly news and wishing she were dead, so we know right away that things have somehow gone hideously, spectacularly wrong. Shortly after entering Darcy Arts Academy on scholarship (she is a gifted singer), Judy accrued a small gang of outsider friends, whom she hoped to social-climb past before too long: Molly, a whip-smart black poet who wears clashing colors; Goth Sarah, who wears ripped fishnets and acts as a one-girl feminist Greek chorus at first, only to slide into an undistinguished loyal-best-friend role when things get heavy, her once promising political analysis shocked into muteness.

Aside from her short stature and vocal talent, Judy is a rather average sixteen-year-old. She swims through her weeks suffused in interpersonal drama, that gloppy, murky medium of adolescent girls. She traffics in trumped-up hyperbole, but there is seldom any poetry in her overstatements. Most of her metaphors and turns of phrase miss their mark, although she occasionally nails one, as when she feels a boy watching her “like in a Planet Earth, Life, National Geographic way—like, I don’t know, I was a scrumptious baby alpaca and could feel some groggy but hungry wolf eyes on my back.” Scrumptious baby alpaca! This sort of keen observation, which adeptly synthesizes a gum-cracking vernacular and pop cultural knowingness with a limpid, unscabrous tenderness, is what Judy does best, but she does it too rarely.

More frequently she attaches rapture and super-romantic adoration to certain people, locations, and experiences just because, insisting that this romanticism serves as its own justification:

There’s no way I’ll ever feel this way again. And I’m glad. I think maybe the very not-realness of teenage love makes it the only real thing. Say what you will if you’re a grown-up, that it’s puppy love when you’re young, that we aren’t going to marry our teenage loves anyway, so they’re just crushes. . . . But none of that matters. . . . And the reason I know that is because I still feel like I’m actually going to die.

The passion of this monologue makes us think we’ll find some wisdom in its profusions. But there is none to be found, only intensity for its own sake, spinning in a tautological reel.

Judy is a narcissist, preternaturally certain of her good looks, her talent, her intelligence, and the popularity and success that are surely just around the corner. She is, in fact, a twenty-first-century achondroplastic bundle of classical hubris, her tale sharpened by one of the oldest dramatic devices in history:

Isn’t that what irony is, when everyone else knows something horrible that’s going on with you but you don’t know it? Like Oedipus killing his dad and about to fuck his mom and the whole audience like, “Oh my god,” and him like, “Life’s too good to be true”?

Her pride will, accordingly, bring her to grief, but the real culprit here is the obsession with the visual that characterizes her generation, who have always played out their lives on screens. The popular boys at Darcy (the academy’s name hinting at a long history of arrogant heartthrobs) all want to go to film school, and the alpha male’s desk at home is piled high with mini-DVDs he has shot of his life: This boy, Kyle Malanack, consumes everyone around him by filming them and luring the girls to bed, and the distinction between these two activities eventually all but disappears. In Big Girl Small, as in Hollywood, the camera is always in a boy’s hands. With the odds thus stacked against girls, to hobble a heroine by denying her powers of real insight is decidedly unfair. Of course, the retort could be that life, for girls both big and small, is often unfair. But where’s the satisfaction in reading another book about that?

Sara Marcus is the author of Girls to the Front: The True Story of the Riot Grrrl Revolution (Harper Perennial, 2010).