A friend of mine recently came to me with the breathless news that he had just slept with a famous porn star. The performer had contacted him out of the blue on an online hook-up site. (My friend was supposed to be spending his day looking for jobs. Frailty, thy name is Manhunt.net). Excited and a little jealous, I asked the obvious question.

"Actually, it was kind of boring," he said. Then he laughed. "Come to think of it, that means it was a little like the sex in a porn movie."

Of course it was—I don’t know why either of us expected otherwise. It’s unfair to expect someone who has sex for a living to give it his all on his days off; you’d never see Novak Djokavic rallying with a stranger on a public court just for the hell of it. But the problem goes deeper than just weary professionalism: the problem is pornography itself. As much as sitcoms and soap ads, skin flicks have mediocrity in their DNA. With porn, there’s not a high barrier to arousing viewers’ interest: sex, no matter how banal, is always going to get some kind of reaction. This makes the field particularly fertile for uncreative work, which chokes out any really innovative filmmaking.

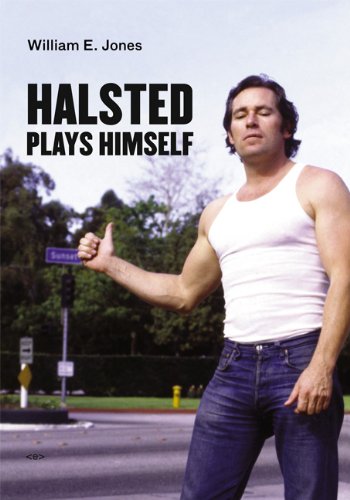

That’s what makes Fred Halsted, the subject of William E. Jones’s new book-length essay Halsted Plays Himself (Semitoext(e)), such a standout character. Active in the early ’70s through the mid ’80s, Halsted broke through with his self-directed 1972 film LA Plays Itself, a charmingly weird triptych of sex scenes. Or mostly sex scenes. The film’s arresting centerpiece in fact has no actual sex at all. Overlaid on images of West Hollywood traffic, Halsted runs audio of a conversation between an older man (voiced by Halsted) and a hayseed (Halsted’s boyfriend Joey Yale). The exchange, the transcript of which Jones reprints in the book, is heavy with erotic potential but the images on screen keep the scene from going overboard. Halsted bucks convention and asks the viewer to do the imaginative work. In the space between the mismatched audio and visuals, the viewer’s erotic imagination stretches to complete the story’s arc, so that when the section ends and the traffic scene gives way to a brief image of Joey Yale undressing, it’s far more satisfying than any number of money shots.

In Halsted Plays Himself Jones offers a passionate appreciation of Halsted’s work in an attempt to resurrect his reputation. At the time of their release, Halsted’s films—disjointed, impressionistic and sometimes violent—stood out from the story-driven porn of the time. While contemporaneous gay porn dealt in clichés of jocks and leathermen. LA Plays Itself was non-narrative, non-linear, and ended with a scene of a penetrative act so violent, it was called perverse even in the porn community. The attention Halsted’s work earned him was equally outsized. His films were screened not only in porn theaters and skid rows, but at MOMA. They were embraced and argued about by intellectuals and artists. Upon exiting a viewing of LA Plays Itself, Salvador Dali was heard muttering to himself, “New information for me.”

Halsted became a major underground figure, but since his suicide in 1989, he’s mostly faded from memory.

Jones is at his strongest investigating Halsted the man. He was a knotty figure, at once innocent and debased, artistically innovative and intellectually shallow. And he was in love, by turns sweet and abusive towards Yale (who, for the record, gave as good as he got). Jones dives deep, investigating even the fringe religious background of the filmmaker’s mother who was born into a radical Christian sect called the Doukhobors. He interviews a number of old lovers whose conflicting accounts present a flighty, passionate Halsted. An old boyfriend revealingly tells Jones that the idea for LA Plays Itself was almost a lark, that it “was made from random footage that we took. There was no plan to it… he had the genius, I suppose, of being able to sort it all out and put it together into some sort of sequence.”

Can that be considered a sort of genius or just dumb luck? In his ardent insistence that Halsted was an inspired auteur, Jones tends to loose sight of Halsted’s weaknesses, which leads to some questionable leaps in his analysis. In a close reading of a boxing-themed S&M scene from Halsted’s Sextool, he writes, “During the sex, Fred is impatient and unpredictable in his violence… Fred’s performance has a carelessness and anger that the film cannot quite explain away.” How, I wonder, might any film “explain away” the anger of a sadistic top towards a willing bottom? What distinguishes the scene from being incomplete, or just fine?

Indeed, throughout Jones is too eager to celebrate Halsted’s films at the cost of giving them an honest critique:

The first time I saw the scene between Fred Halsted and Joey Yale in LA Plays Itself, I was astonished. I consider it one of the greatest in gay porn, if not all of cinema. The continuity is bad, the insert shots intended to comment on the action are heavy handed, and there are needless repetitions in the sound editing. The film is not a masterpiece, as various arbiters have reminded me, and I couldn’t care less.

I understand how the scene described might be novel, but Jones loses me at the greatest scene in all of cinema. It’s hard to trust a critic who’s given to such rapturous hyperbole—and this passage is in the introduction.

Whether or not you agree with his reading, Jones does allow readers to look to the source: the final section of the book consists of primary source documentation of Halsted the porn star. Jones has collected pages of interviews Halsted gave at the height of his career, reviews of his work, and the filmmaker’s own erotic writing and sketches. It’s a fascinating glimpse of a bygone gay culture whose aesthetic was far less polished, more earthy, and more dangerous than our current one, defined as it is by dollars and digital media.

While Jones does a great service to the reader in collecting and including these primary source materials, he does it at the cost of undermining his own Halsted-as-genius thesis. They present an image of a provocateur and dilettante who seems to have stumbled on LA Plays Itself by mistake. In a 1978 interview with Mikhail Itkin, Halsted rambles about how his own belief in gay superiority makes him a fascist (“Gay supremecy is fascistic! What’s the difference between gay supremacy and Nazism?”). Itkin nobly struggles to take him seriously:

MIKHAIL: Well, even agreeing with a large part of that, I remain anti-fascist and still fail to see the analogy to fascism which you’ve drawn.

FRED: Well, fascism maintains that something is better than something else.

Jones contextualizes this kind of statement as a symptom of an identifiable right-wing leaning: “Itkin’s interview reveals that while Halsted’s credentials as a provocateur and sex radical were beyond question, his politics could be more conservative than his public image suggested.” I find it difficult to take seriously Halsted’s thoughts about any kind of political system when he voices such bargain basement, crackpot opinions. His films might express political thoughts—LA Plays Itself contrasts individual desires against urban sprawl, a party in Sextool invites an exploration of race and class—but his speech says very little. Further underscoring this point are Halsted’s own writings. For the magazine Drummer, he produced some sloppy fantasies of truck drivers, cops, and leathermen that are as creatively erotic as an episode of The Red Shoe Diaries.

Halsted just doesn’t seem to have had the informed political ideas or true artistic genius that Jones would understandably like to see in him. But Jones’s overall point is well taken: here is a man who did something novel with a genre that was already tired forty years ago.

——

Did that novel artistry have any lasting influence? It seems unlikely. After all, the cultural importance of Halsted’s work might fail to reverberate now that digital media has upended pornography, making it at once more private (we can see all we need to at our desks) and more public (c.f., Anthony Weiner).

The digital age has de-professionalized porn: those who are so inclined can even star in their own dirty pictures. There are now countless websites that specialize in “amateur” pornography. The clips—and they’re really just clips, never more than a few minutes long—are hazy, single-angle affairs, shot from a video camera trained on the bed. These amateur videos can be seen as rejections of the unreality of slick, corporate porn.

Unfortunately, these home movies are just not very good; they’re as boring and impersonal as any other skin flick, as banal as my friend’s rendez-vous with the porn star. But in their ineptitude and odd popularity, the amateur clips shows how hungry people are for someone like Fred Halsted, someone who can blur the distinction between porn and art. For all Halsted’s uneven edits and blowhard interviews, there is an art and an immediacy to his work that’s evident neither in slick corporate films or quick-and-dirty user-generated clips.

Desire is too complicated and delicate to capture on film in a moment of unthinking passion or unfeeling business. It takes an artist to do it right. Halsted might not have understood fascism, writing, or sound editing, but he was uniquely fluent in the visual language of lust. That’s a legacy worth preserving.

Sam Biederman's essays and criticism have appeared in publications including N+1, Idiom Magazine, and Contemporary Theater Review.