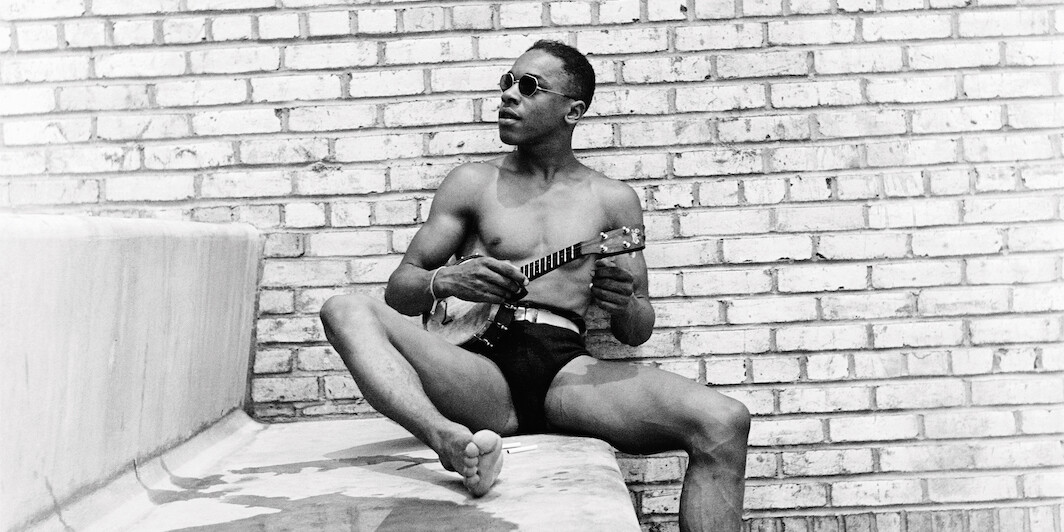

Pierre Fatumbi Verger: United States of America 1934 & 1937

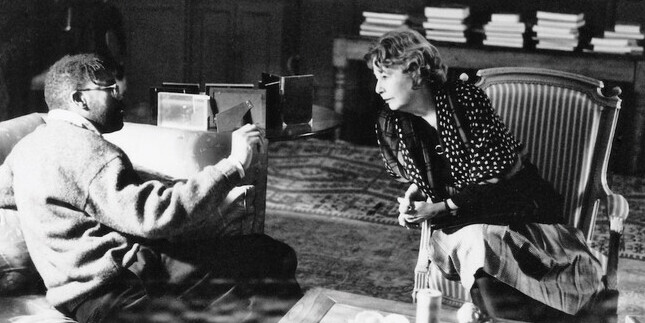

BORN IN 1902, Pierre Verger became a successful photojournalist in his native France, in 1934 cofounding an agency whose members included the likes of Robert Capa and Henri Cartier-Bresson. He lived mainly in Brazil from 1946 until his death fifty years later, and in his adopted country devoted himself to ethnography, writing many books. But he was not a disinterested observer; fascinated by the persistence of Yoruba culture in the New World, he was initiated into the Candomblé religion, and after studying in Benin, he became a Babalaô or high priest of the Ifá oracle, and was accorded the new

![Sonia Delaunay, Robes simultanées (Trois femmes, formes, couleurs) (Simultaneous Dresses [Three Women, Shapes, Colors]), 1925, oil on canvas, 57 1/2 x 44 7/8". © PRACUSA S.A./Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid](http://www.bookforum.com/uploads/upload.000/id25075/featured00_landscape.jpg)