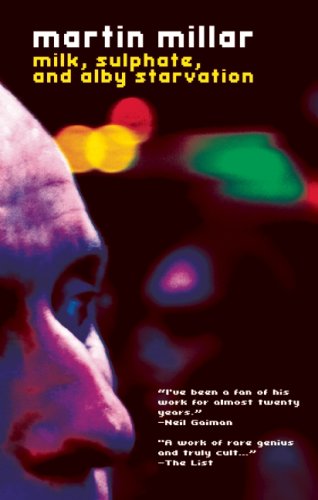

An air of comical amphetamine dependence pervades Martin Millar’s debut novel, Milk, Sulphate, and Alby Starvation. The protagonist, Alby, is a twenty-six-year-old paranoiac and small-time sulphate (i.e., speed) dealer convinced that both Chinese gangsters and the Milk Marketing Board have contracts out on his life. The book’s plot is chopped into raucous little sections that seem to reflect the characters’ short attention spans, while its sentences, in their haste to catalog the chaos, often forgo punctuation entirely. Indeed, one comes to feel thoroughly under the influence of Millar’s lively, hurtling prose.

Milk was first published in 1987, when Millar was thirty and living in Brixton, in South London. A center of urban decay, gang violence, and ethnic conflict, the area was nonetheless an exciting place to be. The narrator describes the streets as rife with “punks and rastas and communists and any other filthy degenerate you care to name, all of them wearing appalling old ripped up second-hand clothing with their hair in bizarre cuts and colours.” Alby is almost willfully destitute, as any display of ambition risks upsetting the slacker equilibrium, wherein spending one’s unemployment checks at the pub is de rigueur, and he retreats at the least sign of pretension: “She puts on the Gymslips who are a sort of female punk band well not exactly punk but sort of well fuck it I’m not a music critic she puts on the Gymslips.”

Millar paints Alby as a kind of punk-rock Bertie Wooster, who, abandoned by Jeeves, has been left to fend off the assault of daily life on his own. He finds such tasks as drying lettuce overwhelming—further evidence of life’s impossibilities. Mirrors, he thinks, are “malicious objects that are out to make me feel bad.” To deal with the stress of it all, he and his only friends, a pair of anarchic lesbians named Fran and Julie, routinely take “enough sulphate to levitate a rhinoceros.” The novel’s humor stems both from the copious drug consumption and from the reader’s suspicion that Alby’s troubles are self-inflicted. Yet his ostensibly speed-induced paranoia turns out to be well founded: A Brazilian-trained, female assassin is trying to kill him, and a Chinese drug financier is tracking him down. Brixton, we’re reminded, is a legitimately, though often hilariously, dangerous place to live.

Millar has written many novels since Milk’s original publication, including Lux the Poet (1988) and Suzy, Led Zeppelin, and Me (2002). He is frequently labeled a cult author and would be unlikely to claim Milk as a work of high literature. Yet the story consistently impresses. It is told alternately in the first and third persons—the former reserved for Alby, the better to explore his strange, afflicted consciousness; we see him both as a fully developed human and as a comic-book caricature of young, urban degeneracy. The novel is similarly fractured: Blunt portrayals of squalor and loneliness coexist with fanciful depictions of psychic nurses, magic crowns, and Zen-master video-gamers. A low-life fairy tale, Milk preserves a strong sense of hard-earned realism, excusing the reader for any guilty pleasure he or she might take in reading it.

Jed Lipinski writes for the Village Voice and the Brooklyn Rail.