It is a favorite ploy of conservative aggregator Matt Drudge to invoke “Chicagoland” when he wants to imply that the Obama White House, rife with Second City political operatives, has taken a page from the playbook of the Chicago Democratic Machine, which established its fiefdom on the shores of Lake Michigan.

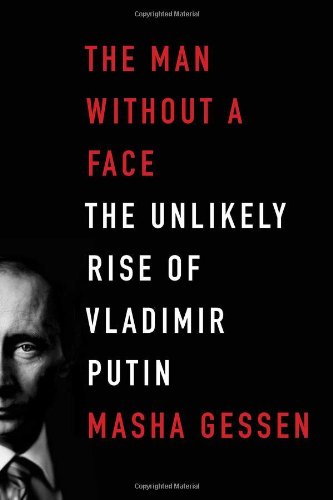

For many Russians, St. Petersburg has the same crooked connotations. On the edge of Russia and on the cusp of Europe, it has never really been part of either. And as Moscow-based journalist Masha Gessen writes in The Man Without a Face: The Unlikely Rise of Vladimir Putin, Petersburg’s reputation is much more deserved than Chicago’s. She calls the city that survived a nine-hundred-day Nazi siege “a mean, hungry, impoverished place that bred mean, hungry, ferocious children.”

One of those nurtured in its frigid womb was Putin, who earlier this month was handed—"elected" is far too charitable a word—his third term as Russia’s president. In this book, written in English but with Russian heart, Gessen focuses on the places and institutions that bred the nation’s most resolute leader since Stalin, whose reputation Putin has tried to rehabilitate.

“All of Russian history happens in St. Petersburg,” Gessen writes in a pleasurably bold pronouncement. Gessen makes a strong case for Putin being a creature of Petersburg’s corrupt political culture, detailing how Putin managed to stock the Kremlin with cronies whose fealty was first to him, then to their own bank accounts (foreign, to be sure), and somewhere farther down on that list, to the Motherland itself.

Yet despite Putin’s ties to Petersburg, no one could have predicted that a self-described “thug” would become one of the country’s leaders. In fact, there is little remarkable about him. He was a product of the middle class: His mother was a factory worker and his father served in the war and was seriously wounded. Having already lost two sons, the Putins must have felt the need to nurture their first child to maturity. Even in the lean postwar years, young and not-especially-exceptional Volodya was given a car, and generally lived better than those around him.

To exist comfortably during this period might have made others grateful, but it seems to have turned Putin into a pathologically entitled bully. In her book’s most remarkable claim, Gessen posits that Putin suffers from pleonexia, “the insatiable desire to have what rightfully belongs to others,” which has driven him to plunder the nation’s coffers and amass a wealth that was estimated at $40 billion in 2007 and may be much greater today.

Before he assumed power, Putin took up the rigorous martial-arts practice of Sambo, studied law at the Leningrad State University, and joined the KGB in 1975, where he rose through the ranks, specializing in foreign intelligence. In 1985, the promising young spy was assigned to the East German city of Dresden (a backwater for a promising young agent) where he “drank beer and got fat,” in an abdication of self-discipline he has yet to repeat.

It was just before the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991 that Putin returned to his homeland. Many others were going into business; Putin decided to enter government, where he earned a reputation for incorruptibility in the office of Petersburg governor Anatoly Sobchak, who presided over a city that resembled Jazz Age Chicago, except with unpaved roads and worse music. Putin’s unlikely reputation persisted long after Sobchak’s downfall, though Gessen reveals that many of the $92 million worth of municipal contracts Putin oversaw may have been illegal.

But these were the Yeltsin years, so who could say what was or wasn’t illegal? In 1991, Yeltsin took office on promises of ushering in democracy. But that very quickly turned into chaos: Men who had been paupers were made titans of industry overnight. War simmered in Chechnya; the recrudescence of Communism haunted the land. If there was law, it was only the most primal kind. By the mid-90s, it was common in Russia to refer to democrats as dermocrats, which translates, more or less, to “shitheads.”

It was through Yeltsin’s increasingly dissolute Kremlin that Putin made his determined ascent. Gessen charts his path deftly, with sorrow over a rise that could have been prevented had more courage and less cash flowed through the veins of the Kremlin.

“Possibly the most bizarre fact about Putin’s ascent to power is that the people who lifted him to the throne knew little more about him than you do,” Gessen writes of the oligarchs who Yeltsin made wealthy. But by the late-90s they had wearied of his lurching leadership. They deemed Putin to be “a friend,” elevated him first to prime minister and then handed him the presidency on New Year’s Day of 2000—all without his ever having been elected to office.

He learned quickly, though. Gessen analyzes (and ultimately agrees with) a long-standing charge that the Federal Security Services engineered a series of apartment bombings that killed 293 people across Russia in late 1999, giving Putin an excuse to return forces to Chechnya. He was still prime minister at the time, but cleared to assume the presidency.

One imagines, while reading passages in which Gessen has ex-cons smuggling explosives into basements at the KGB’s behest, that 9/11 “truthers” would find fertile ground in Russia. Gessen notes that of the first eleven edicts Putin made during his first two months in office, six dealt with the military. In the wake of the 1999 attacks, Putin made his hardline stance towards terror clear: “We will hunt them down. Wherever we find them, we will destroy them. Even if we find them in the toilet. We will rub them out in the outhouse.”

But as Putin would learn, that military was as rotten as the rest of Russia. When the submarine Kursk sank in August 2000 and 118 people on board were killed, it was partly because Putin had refused international help. At this point, Gessen writes, it finally dawned on him that “he now bore responsibility for the entire crumbling edifice of a former superpower.”

Like his cowboy counterpart in Washington, Putin learned to use the threat of terrorism as a means of expanding his own power while hiding the serious failings of his administration. But while Bush was incompetent, Gessen argues that Putin was not—instead, he was cold-blooded in his estimation that even if the bloody Chechen campaign reached the heart of Russia, the consequent terror would serve his political ends.

From the 2002 Nord-Ost theater attack in Moscow (129 dead) to the 2004 Beslan school siege in the Caucasus (344 dead), Gessen shows how Putin’s Chechen war became the bloody centerpiece of his administration, allowing him to project toughness while the Russian people suffered. Meanwhile, by jailing the oil oligarch Mikhail Khodorkovsky and making sure that media kingpins Boris Berezovsky (exiled in England) and Vladimir Gusinksy (exiled in Israel) were stripped of their holdings, Putin consolidated state control of the economy as well as of newspapers and television channels.

Some might say that Gessen’s interpretation is political. Of course it is; for an apolitical account, one is advised to find a textbook. But more importantly, it is thorough. She has seen fellow journalists killed, has been harassed herself, and yet continues to write from Russia, not the safety of a Washington think-tank or London townhouse. Her urgency is felt on nearly every page.

A similar urgency pervaded the reporting of Anna Politkovskaya, who was gunned down in 2006 in a grim message—though its ultimate sender remains unknown—about what happens when you meddle with the affairs of the Kremlin. Today, Russia is one of the least safe places in the world for journalists. That is, unless they are willing to serve as shills for the Kremlin, which Gessen certainly is not.

The book ends during last December’s protests, after it was clear that Putin’s political party, United Russia, had brazenly rigged parliamentary elections in its favor. Though the demonstrations against him were inspiring, they did not prevent Putin from earning a third presidential term three months later. In a sentence as simple as it is damning, Gessen concludes, “Putin changed the country fast, the changes were profound, and they took easily.” As fine as The Man Without A Face is, it betrays a certain hopelessness about Russia, a futility that recalls the writing of dissidents during the Soviet era. It also shares a particularly Russian flair for the tragic. As a museum curator tells Gessen: “What a shitty time we’ve lived to see.”

Alexander Nazaryan is the editor of the Page Views book blog at the New York Daily News and is on the paper’s editorial board. He is at work on his first novel.