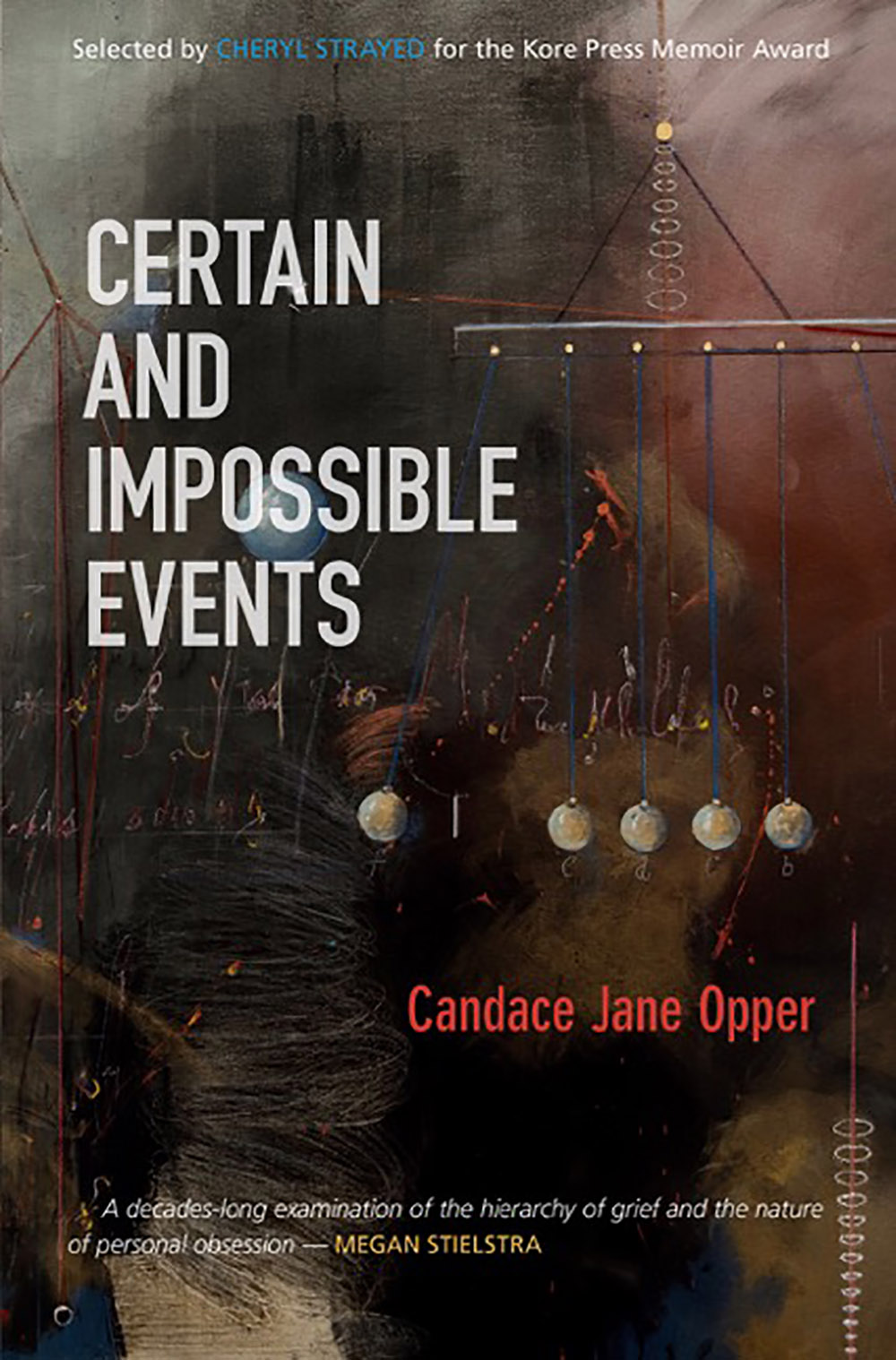

Grief memoirs typically meditate on the loss of someone so close to the author that they could have listed the deceased as an emergency contact. Candace Jane Opper’s Certain and Impossible Events is not that kind of memoir. The book revolves around the death of a boy Opper wasn’t exactly close with—a crush whose phone number she memorized when she was thirteen. He died by suicide, at age fourteen, in 1994, eight days after Kurt Cobain’s body was found. More than twenty-five years later, Certain and Impossible Events is Opper’s attempt to map her ongoing obsession with the boy’s death.

Normally, I would be allergic to writing that centers the experience of someone on the periphery of grief. Both of my parents died when I was a young teen, and the intensity of my loss has made me cynical about the possibility that someone could use the death of an acquaintance as a way of talking about themselves. But in pushing back against the hierarchies of grief that prescribe whose pain deserves to be aired, Opper illuminates the ripple effects of suicide—“a bizarre kind of loss, full of answers and empty of ways to access them”—and how the violence of a life ended early can leave even casual acquaintances reeling.

Opper hasn’t even earned the right to use the boy’s real name (she calls him “Brett”), but the all-consuming crush she had on him felt intimate, turning her from a schoolgirl to a private investigator. Opper writes, “I knew you as the sum of details an infatuated teenage girl picks up on: the contents and rotation of your wardrobe, the path of hallways you navigated between classes, the license plate number on your mother’s minivan.” After his death, her obsession turned toward reconstructing his suicide, looking for “the error in an equation whose faultiness I’m still bent on proving.”

Opper transports us to the churn of her Connecticut junior high, where the news of Brett’s death spread through games of telephone: “That a boy we knew had killed himself steamed with novelty for a while, moving from mouths to ears over lunch or sandwiched between faded green seats on a school bus, lingering finally inside loud whispers in the smoky bathroom before slowly dissipating into the collective past.” Opper wasn’t done talking, and Certain and Impossible Events is the culmination of a nearly three-decades-long conversation with herself.

Opper began the project in graduate school, where she started researching the cultural and scientific understanding of suicide, giving her fixation the gloss of academic rigor. Of course, despite hours in libraries and at conferences, she doesn’t find definitive answers. Certain and Impossible Events reminds us that it is the living who make sense of the dead. And as “culture, religion, zeitgeist” shift, so too does the meaning we ascribe to teen suicides like Brett’s.

The moral panic du jour searches for easy answers, and it would have been easy to say that Brett’s suicide was explained by Cobain’s. Brett was found with a copy of Entertainment Weekly, with Cobain’s face on the cover, in his back pocket and a Nirvana CD at his feet. Interestingly, Opper doesn’t mention the Cobain connection until halfway through the slim memoir, after immersing us in the worlds of junior high and suicidology. I was surprised to learn that researchers didn’t see a demonstrable contagion following the singer’s suicide. In a paper titled “The Kurt Cobain Suicide Crisis” sociologists wrote, “Cobain’s suicide may have significantly and positively increased the public awareness about suicide, crisis services, and available treatment.” Ultimately, Opper does believe that Cobain’s death played a part in Brett’s suicide, but the copycat theory doesn’t satisfy her. She feels such a theory risks “oversimplifying your motivations.”

Opper’s use of the second person to address Brett here, as she does throughout the book, emphasizes that her writing is one way to keep the conversation—one that never really started—going. What was missing from Certain and Impossible Events for me was a sustained effort to answer why she has found herself stuck in the groove of Brett’s story. It’s clear that his suicide shaped her life, but we get very little of that life outside of her obsession. At one point, Opper identifies herself as an Adult Child of Suicide—a demographic made up of people who “experience[d] suicide loss at a young developmental stage and [were] not offered adequate grief support.” But the original trauma alone doesn’t explain a fixation that led her to get Brett’s real name tattooed between her shoulders on the thirteenth anniversary of his death. Toward the end of the book, she writes, “So why do some of us remain unhinged? Perhaps I’d find the answer if I looked closer at the sum of my own experiences, instead of yours.” Yes.

Kristen Martin’s essays and criticism have appeared in The Baffler, Literary Hub, The Cut, Hazlitt, Real Life, and elsewhere.