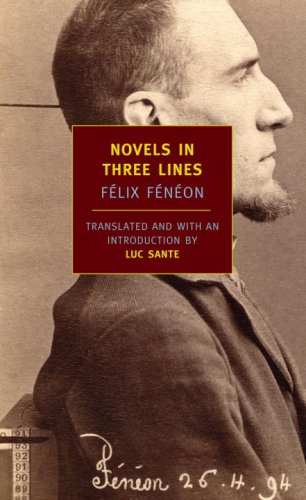

Anarchist and aesthete, Félix Fénéon was a pivotal, if not unavoidable, figure in fin de siècle Paris. He promoted the careers of Seurat, Bonnard, and Toulouse-Lautrec; a regular at Mallarmé’s salon, he edited Rimbaud’s Illuminations and published the first public edition of Lautréamont’s Chants de Maldoror. Failure to publish a book of his own (at least during his lifetime) didn’t inhibit his reputation as an elegant stylist, though much of what he wrote appeared anonymously. Such was the case when, in 1906, he began producing three-line items for the Parisian daily Le Matin. The results of this six-month occupation have been handily translated by Luc Sante and collected in a pocket-size volume that’s ideal for filling unemployed moments on train platforms or your doctor’s examination table.

These fillers, or faits divers, which were originally published under the headline “Nouvelles en trois lignes,” recount all manner of assault, graft, accident, labor strife, and murder in spare, factually tidy detail. While the title given by the newspaper was surely somewhat in jest, in fact Fénéon’s high-density précis do feel spring-loaded, as though much longer tales might burst forth if even one more sentence were permitted: “Sixty-year-old M. Bone, of Andigné, Sarthe, had, when drunk, so badly beaten his maid that he was to be arrested. Irked, he hanged himself.” Bone’s entire backstory—a lifetime of angry truculence and spiked resentment— is compressed into irked.

One especially entertaining strategy for reading this compendium is to organize the entries into genres of mayhem and then to delight in the variations of method and motive within, say, reports of suicide: “In Le Havre, a sailor, Scouarnec, threw himself under a locomotive. His intestines were gathered up in a cloth”; “Charles Delièvre, a consumptive potter of Choisy-le-Roi, lit two burners and died amid the flowers he had strewn on his bed”; “‘If my candidate loses, I will kill myself,’ M. Bellavoine, of Fresquienne, Seine-Inférieure, had declared. He killed himself”; “Married for three months, the Audouys of Nantes committed suicide with laudanum, arsenic, and a revolver”; “The Englishman James, a suburban celebrity (athletic feats, rowing), cut his throat at Courbevoie; he feared becoming insane.” For his microtales, Fénéon supplies— in an elliptical prose that anticipates noirish deadpan—the often comic, sometimes riddling, but always piercing particulars: the Audouys’ overkill, the potter’s strewn flowers, the violent spasm that confirms the Englishman’s fear.

These epigrammatic plots invite being read aloud, as well as other diversions. One can speculate which novelist might best take up a breviary and run with it: “The bones found on Île Verte in Grenoble comprised not two but four children’s skeletons, minus two skulls.” Cormac McCarthy or Joyce Carol Oates? Such arrestingly grotesque images proliferate as Fénéon winnows down the sprawling human tale to an assemblage of final things—ropes and razors, collisions and incisions. Each of us may believe that his or her own life is a novel, but when it comes to what others—over their morning coffee—want to know about us, it’s a very, very short book, indeed.