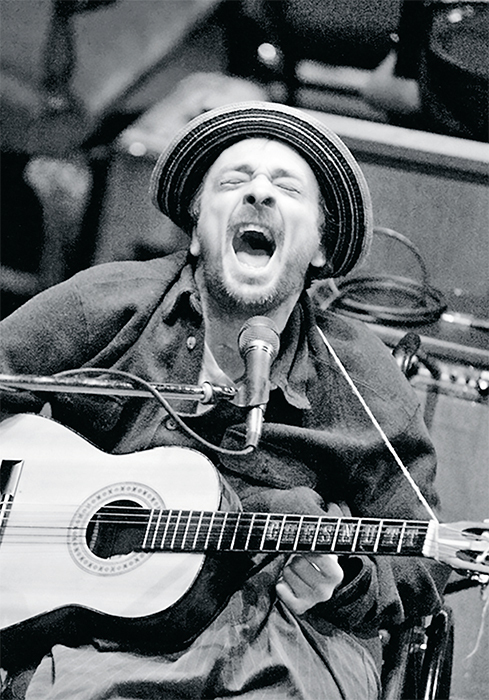

When he was eighteen, southern singer-songwriter Vic Chesnutt was in a car accident that partially paralyzed him from the neck down. He had been drinking and flipped his car into a ditch; no one else was hurt. Chesnutt would never walk again, but about a year after the crash he regained limited use of his arms and hands—just enough to play a few simple chords on the guitar. “My fingers don’t move too good at all,” he told Terry Gross in a 2009 NPR interview. “I realized that all I could play were . . . G, F, C—those kinds of chords. And so . . . that’s what I was going to do.” Working within these limitations, and, in a way, finding his aesthetic through them, Chesnutt began a prolific career, making barbed, plainspoken, and darkly lovely folk music for two decades. He recorded sixteen albums, all of which undercut tales of pain and suffering with a macabre humor and a certain kind of hard-won pride. “I’m not a victim,” he hollers on his great, Michael Stipe–produced debut album, Little (1990), “I am an a-the-ist.”

Both before and after the accident, Chesnutt struggled with addiction and depression, and he attempted suicide several times. He had always been candid about this in his lyrics, but in September 2009, he released an album with one of the most affecting odes to melancholy he’d ever written, “Flirted With You All My Life.” At the start, the song seems like a simple tale of unrequited love (“When you touched a friend of mine / I thought I would lose my mind”), but about halfway through he reveals that the person he’s addressing in the song is, actually, Death. (This is Chesnutt’s idea of a punch line.) “I’ve flirted with you all my life,” he rasps over a bed of incongruously pastoral strings, “ / Even kissed you once or twice / And to this day I swear it was nice / But clearly I was not ready.” “It’s kind of, you know, it’s a breakup song,” he told Gross that day in December 2009. “It’s a suicide’s breakup song with Death.” He said it with convincing optimism, as if maybe he’d finally driven the demons out for good. Then, a few weeks later, Chesnutt overdosed on muscle relaxants. He died on Christmas Day, at the age of forty-five.

Especially when it comes to beloved musicians, these are precisely the kinds of stories—a tragic, self-damning injury; years of chronic pain; an atheist’s death on Christ’s birthday—that lend themselves to lazy posthumous romanticization. And as anyone who has listened to Chesnutt’s music or read a single interview with him can attest, he hated few things more than lazy romanticization. As his friend Kristin Hersh points out in her new memoir, Don’t Suck, Don’t Die: Giving Up Vic Chesnutt, misfortune had turned him caustic and prickly. The man she describes made fun of strangers loudly, and always within their earshot. He proudly self-identified as a “dickhead.” The outgoing message on his voice mail instructed the caller, who more often than not was a loved one, to “fuck off.”

How do we eulogize the difficult dead? How do we pay tribute to artists who struggled with addiction and depression without fetishizing their pain? These questions seem to be in the air right now, and two recent much-talked-about films have failed to provide satisfying answers. One is Brett Morgen’s HBO-produced Kurt Cobain documentary, Montage of Heck (2015), an impressively edited but overwhelmingly dour bit of grief porn that will single-handedly keep the Cobain-Industrial Complex humming for the immediate future—at least until someone discovers another volume of his journals to publish. Slightly better is Amy (2015), Asif Kapadia’s poignant film about Amy Winehouse, which blames the tabloid press for her downfall—but in the end feels a little too eager to use, for narrative purposes, the very sensationalized images it purports to critique. Although he had a cult following, Chesnutt wasn’t, of course, a household name like Cobain or Winehouse. But Don’t Suck, Don’t Die feels particularly refreshing compared to those films in the rare way it resists the urge to simplify, mythologize, or luxuriate in its subject’s struggles.

A celebrated musician herself, Hersh has had a fruitful career as a solo artist, but she’s perhaps best known as the warbling-voiced front woman of ’80s art-rock exorcists Throwing Muses. In 2010, Hersh published Rat Girl, a vivid and rightly acclaimed memoir about one eventful year in her life, during which she was diagnosed as bipolar, got pregnant, and recorded her band’s self-titled breakthrough debut album. The year was 1985; Hersh was nineteen. Rat Girl has verve and a voice that combines teenage punk-rock enthusiasm with a cracked, Southern Gothic sensibility; at times it reads like a zine written by Flannery O’Connor. Like Chesnutt’s, Hersh’s muse was awoken by, of all things, a car accident: “I’ve heard music that no one else hears since I got hit by a car a couple years ago and sustained a double concussion,” she writes in Rat Girl. “I didn’t know what to make of this at first, but eventually I came to feel lucky, special, as if I’d tapped into an intelligence. Songs played of their own accord, making themselves up; I listened and copied them down.”

Hersh and Chesnutt met very briefly before his accident, but they became fast friends many years later, in 1994, when they embarked on a joint European tour. The bulk of Don’t Suck, Don’t Die recounts this time, especially the banal moments between transcendent performances: They argue at truck stops over lukewarm instant coffee, joke during sound checks, philosophize at crappy motel after crappy motel. Hersh is at once a kindred spirit and a foil to Chesnutt, enduring her own inner turbulence while also beckoning her more troubled friend toward the light. Early in the book, she tries to force him out of a sour mood by foisting a bag of Jolly Ranchers on him and—much to Chesnutt’s disgust—attempting to draw some kind of moral from the scene. “Grab sugar wherever it falls,” she says, dropping a fistful of candies into his lap. Chesnutt, meanwhile, maintains a different worldview: “What touring ‘affords’ you is a fresh opportunity to be a DICKHEAD, every-fuckin’-where you go!”

Don’t Suck, Don’t Die is written entirely in the first person, with Hersh directly addressing her absent friend—and seeming aware that he would probably object to many of her pronouncements. (This imagined interplay can be very affecting: “I’m sorry,” Hersh writes. “Even though you hated sorry, I’m still sorry.”) The subject of the book is neither Chesnutt nor Hersh but the space between them, a platonic friendship so charged that people sometimes mistook it for something else. After one of their joint shows, a fan thanks them for helping him win a fifty-dollar bet. “My friends didn’t believe that Kristin Hersh and Vic Chesnutt were married,” he says, triumphant. “You mean to each other?” Hersh asks him. Chesnutt clarifies the matter in his self-deprecating way: “Naw, we ain’t married. She’s married to a real man.”

This focus on Hersh and Chesnutt’s relationship gives the book a heightened intimacy—but as the sole work about this unsung songwriter, it also makes it feel slight and limited in its scope. Hersh knew Chesnutt well for only the last fifteen years of his life, and beyond a scattering of facts he obliquely reveals in their conversations, the basic story of his early life and career goes entirely untold here. The book left me eager to know more about the major events of his life—how he started playing music; how he met his wife, Tina; why he made a conscious retreat from alt-rock fame when, thanks to famous fans like Stipe, he had the opportunity to pursue it in the mid-’90s. (In 1996, Chesnutt released one of the most wryly titled major-label debuts in music history: About to Choke.) As much as we learn about Chesnutt from his interactions with Hersh, the book would have benefited from a few well-placed zoom-outs.

Fittingly, the book’s most poignant moments come when Hersh is not afraid to tease or even insult Chesnutt; by the end of it, the reader knows him well enough to realize this is exactly how he’d have liked to be eulogized. (She sometimes calls him “Bitch Chesnutt,” a term of endearment.) In one of the memoir’s final scenes, she sits alone in his room after his funeral, near his vacant wheelchair and silent guitar. “When it came to you,” she writes, “I was empty and emptiness was perfect. Doesn’t sound like me to be that Zen, but there it is. I used to know you and that’s all. Dying makes people seem important, and that’s too much responsibility for a soul that’s no more or less than any other.” Here, at last, she’s arrived at the perfect epitaph—an unsentimental elegy for an unsentimental man.

Lindsay Zoladz is New York magazine’s pop-music critic.