For centuries, writers have sat on benches and made up stories about passersby. Vasily Grossman, Andrei Platonov, and Semyon Lipkin would do this while sitting opposite Platonov’s apartment building in Moscow in the 1930s. Lipkin, the least known of the trio, recounts that the stories Grossman invented were matter-of-fact, journalistic, whereas Platonov’s, rarely grounded in the practical, were more concerned with a character’s interiority, which was “both unusual and simple, like the life of a plant.” This distinction also applies to their prose: Platonov created worlds, and Grossman, the more traditional writer, adamantly stuck to the World. But while Platonov eschewed the factual, and Grossman the notional, what’s strange is that these two almost opposite approaches ended up yielding closely related results. There might not be any of Platonov’s talking Communist bears or cigarette-smoking skydivers in Grossman’s oeuvre. But Grossman did write about a cosmonaut dog howling in orbit, elderly folks sitting on benches overlooking a human grill pit where flesh smolders, and a burly commissar abandoning her newborn to triumphantly march off to her death; after all, these peculiar scenarios were Grossman’s reality.

Born in 1905 in Berdichev, Ukraine, it might be simpler to list the important historical events of the first half of the twentieth century that Grossman didn’t witness. At the outset of World War II, this overweight, bespectacled, generally weak writer became a correspondent for Krasnaya Zvezda, a Red Army newspaper, and his acclaimed firsthand accounts of the major battles of that war made him famous throughout the Soviet Union. His elaborate reports of Nazi death camps were among the earliest, and were delivered with an urgent, shifting, rarely frantic but often sublimated tone. “The Hell of Treblinka”—which appears in The Road, a new edition of Grossman’s writings, many of them never before translated into English—appeared in the fall of 1944, just a little over a year after the last of Treblinka’s corpses were burned. Of course, his success as a journalist didn’t prevent him from experiencing the brunt of Stalin’s disfavor. Though Grossman himself narrowly escaped arrest, his major literary work, the novel Life and Fate, was “arrested” in February 1961; at the time of his death in 1964, Grossman had no reason to hope for its publication.

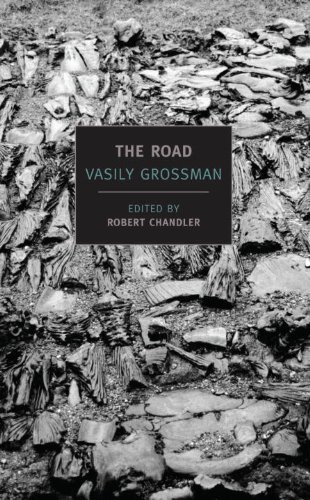

Recently, New York Review Books has been steadily providing indispensable translations of Grossman’s work, notably Life and Fate (2006) and Everything Flows (2009). Now they’re releasing The Road, an assortment of Grossman’s short fiction, essays, journalism, and even two letters he wrote to his dead mother, Yekaterina Savelievna, who shared the fate of the entire Jewish population of Berdichev—in September 1941, all thirty-thousand were killed in an airfield outside the town in the first Einsatzgruppen massacre perpetrated in the Ukraine. Grossman learned of her death upon returning to Berdichev in 1943, by which time no trace was left of those for whom he had returned.

The last piece included in The Road is “Eternal Rest,” a loosely assembled essay (a rough draft made presentable posthumously by his daughter) about the life of a cemetery: “It’s Sunday. Where can you go? To the zoo? To Sokolniki Park? No, the cemetery’s more enjoyable. You can do a little leisurely work, and you can get some fresh air at the same time.” These visitors are the lucky ones, those who were able to secure a spot for their relatives in the lush and prestigious Vagankovo cemetery. Most weren’t so fortunate. “There is very little space. The deceased—in the words of one of the cemetery workers—‘just keep piling in.’ And not one of them wants to go to Vostryakovo [a lesser cemetery].” Indeed, Grossman spent much time in Vagankovo cemetery after his father was buried there in 1956 (ironically, the author himself wasn’t granted a plot in the overcrowded graveyard when he died eight years later). Though his father inspired the piece, it is even more haunted by his mother. She, after all, was deprived of a grave altogether. But the essay’s conclusion argues against the significance of memorial flowers, tidy tombstones, and even mourning, because, in the end, “the sanctity of the soul’s holy mystery makes everything else seem contemptible.” Grossman’s meditation ultimately isn’t about what his mother and millions of others were denied, but the opposite—what one cannot be denied.

Then there are the works of short fiction—harder to remark upon only because they are even more suffused with “the soul’s holy mystery.” Grossman always wrote within the margins of historical truth, and many of his later stories respond directly to contemporary events. “Living Space” is about an elderly woman who returns to Moscow after 19 years in the camps, inspired by the release of hundreds of thousands of prisoners from the Gulag between 1953 and 1956; “Mama,” one of the collection’s gems, is based on the true story of Natalya Yezhova, an orphaned girl who was adopted by Nikolai Yezhov, the head of the NKVD between 1936 and 1938, at the height of the Great Terror.

Throughout The Road—in both the fiction and nonfiction—the facts serve as a mere skeleton to a highly personal drama. But Grossman’s talent is that of subtlety and evenness, of not overburdening. He can inflate a scene with one quick, easy breath, and then allow it to rise on its own. By treating momentous, grave occurrences with lightness, Grossman manages to add to their startling effect.

Yelena Akhtiorskaya is a writer in New York City.