Atossa Araxia Abrahamian

In 2011, Muammar Gaddafi addressed world leaders with a prescient threat. If they intervened to end his shaky rule in Libya, he told a French journalist, they would be inviting “chaos, Bin Laden, armed factions . . . You will have immigration, thousands of people will invade Europe from Libya. And there will no longer be anyone to stop them.” The idea of buying citizenship tends to invoke Bond villains or the louche drifters in Graham Greene’s novels. But it’s also a very real practice that offends nationalists, rankles politicians, and incites populist rage. It hints at a breakdown of the social contract, a “marketization” of everyday life that was practically unimaginable just ten years ago, and perhaps even the creeping obsolescence of the nation-state itself.

When Daniel Levin Becker was sixteen, he made a mixtape that included only songs and artists whose names did not contain the letter e. Soon after, he read Georges Perec’s La Disparition, a novel written entirely without the offending vowel. Levin Becker spent a good part of his formative years “making the numbers and letters on license plates into mathematically true statements,” so he was heartened to discover that he was “not alone in appreciating naturally occurring palindromes, or knowing a shorter sentence with all the letters in the alphabet than The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog, At a time when unions are floundering and popular sentiment toward organized labor is at an all-time low of 45 percent, one workers’ organization is thriving. The Freelancers’ Union, a nonprofit organization based in a trendy Brooklyn neighborhood, has more than 80,000 members in New York and 150,000 members in other states. In the seven years it has existed, the Freelancers’ Union has opened its own fully owned, for-profit insurance company, The Freelancers’ Insurance Company, and has put in place a retirement plan for independent workers. The organization hosts networking events and political canvassing; raises money for politicians who advocate

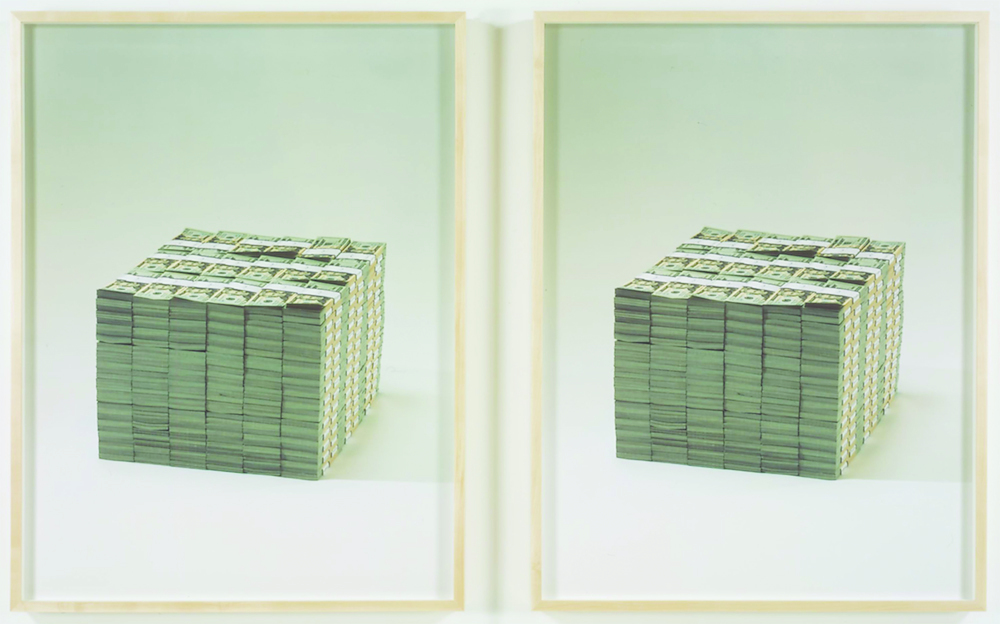

For most of us, money seems like the realest thing there is. It dictates what we eat, where we live, and how long we stay alive at all. Worse still, it seems there’s never enough of it to go around. But what is money, exactly? Where does it come from, and who controls how it’s made, spent, lent, disbursed, and denominated?

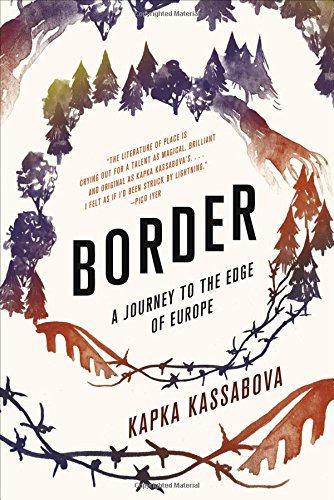

There is an essential arbitrariness to borders. Whether enforced by walls and fences or through less material means—visa requirements, travel bans—they are always at least partly abstract: imaginary lines. Kapka Kassabova’s travelogue Border: A Journey to the Edge of Europe explores the spiritual, psychological, and emotional qualities of the area around the shared frontiers of Turkey, Greece, and Bulgaria, roaming this “back door to Europe” in an effort to find out, up close, what borders do to people, and vice versa. Her book is a deconstruction of the looming, nonspecific anxiety that comes from continually having to justify your right

THE ORIGIN STORY of the 2008 financial crisis is now well known: An American real estate bubble inflated by a risky mortgage business burst. Wall Street got clobbered, spooking lenders, constricting credit, and pushing even low-risk money market funds to register losses. Banks failed; insurers ran out of cash; people—especially minorities and the poor—lost their homes, their jobs, and their money, while the architects of the system suffered few consequences.