Who can resist a diary? They promise intimate revelations—the confidences that let us glimpse the human condition, which we turn to literature for but don’t always find—alongside the rhythms and texture of life as we live it, day by day. And each diary is unique; each represents a specific set of circumstances met by a specific mind. It’s fun to dip into John Cheever’s and then Franz Kafka’s, like moving between an icy pool and a hot tub—a pleasant shock.

- review • July 28, 2022

- review • February 16, 2021

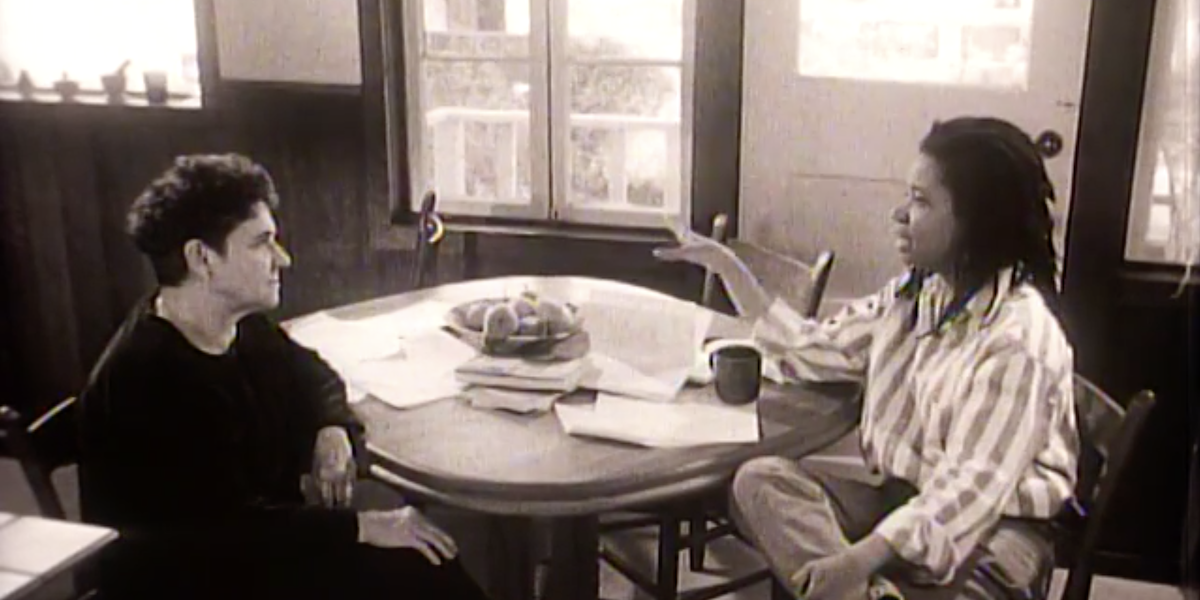

Towards the end of the 1996 documentary, Listening for Something…, Dionne Brand gently corrects Adrienne Rich, specifying that Brand does not write “for” Black people, but “to them.” The differences between these two approaches are both subtle and profound. “For” implies a gifting, something that can be accepted—or put on a shelf and ignored. “To” implies a momentary communion, and asks for engagement and togetherness. While the entire conversation between these two brilliant poets gives the audience plenty to think through some twenty years later, it is Brand’s remark that I’ve carried with me and thought most intensely about in

- review • October 13, 2020

There is an admonition James Baldwin made somewhere that sticks with me. It moved me enough to make a note on a scrap of paper—too hastily to cite title, text, page number. “Baldwin does not say that systems of power are unimportant,” I scratched out. “He insists that liberation is also a mandate on individuality: how one separates oneself from the ‘habits of thought [that] reinforce and sustain the habits of power.’”

- review • July 2, 2020

Several years ago at a friend’s wedding reception, the mother of the groom said to me, “I hope someday you get to experience the joy of a child.” She paused for a moment, then followed up: “Or perhaps you don’t need to, since you’re a writer.” Though many might object to the idea that a book and a child are interchangeable, there’s a long history of comparing—and conflating—these two creations. (After all, what was Ulysses if not Joyce’s attempt to rival parturition in linguistic form?) Writers, both those who are mothers and those who aren’t, have long sought to demonstrate

- review • February 13, 2020

Of the fifteen women who have received the Nobel Prize in Literature, six are from Eastern or Central Europe. Born between 1891 and 1962, in the stretch of land from East Germany to Belarus, these Nobel women differ wildly in the way they write—especially about power and hopelessness, two subjects they all share. There’s Elfriede Jelinek, whose 1983 novel The Piano Teacher uses BDSM as a way of talking about abuse and deviance. Then there’s Svetlana Alexievich, whose renderings of Chernobyl testimony are as spare and haunting as the exclusion zone itself. And, of course, there’s Olga Tokarczuk, whose dialogue

- review • February 6, 2020

In books on the borderlands, the white gaze abounds: Latinx authors are told there’s just no budget for our stories, while seven-figure advances are granted to establishment writers who consider the border from a distance. Jeanine Cummins’s American Dirt, a book about a woman and her son fleeing Mexico for the United States, was quickly anointed by Oprah Winfrey as a must-read. The fact that it was written by a white, nonmigrant novelist at first failed to register. (Soon after, nearly one hundred authors asked Winfrey to reconsider.) The controversy was the latest illustration of how literature suffers when writers

- print • Feb/Mar 2020

Unlike television—where every profession is indicated through props, like a cup from Starbucks—novels often let their characters do the work. Work is a fount of material, what with the complaining, cheating, procrastinating, backbiting, tedium. Not working too. Being unemployed is taxing! Every novel about a rich person who doesn’t work could be marketed with the tagline Everybody works. And who can argue with that? Not a writer.

- review • December 6, 2019

In a review of Ian Penman’s excellent essay collection It Gets Me Home, This Curving Track, I talk about the chaotic, bossless froth of pop-music criticism. I conclude that the practice is healthy. In support, I offer this bowl of noodles, an undisciplined syllabus designed to index the variety and vitality of critical writing tethered to pop. I didn’t look for anything—they came to mind, unbidden. First, some pieces that have been on my counter for a year or so, and, after that, older essays that still guide me.

- review • September 30, 2019

The musician and producer Annie Clark (aka St. Vincent) recently posted to her Instagram a snapshot of a book review by George Packer in The Atlantic which sparked a minor political scuffle among her followers. The review, ostensibly of Dorian Lynskey’s The Ministry of Truth: The Biography of George Orwell’s 1984, was framed as highlighting the novel’s enduring importance while also exhorting readers to remember that the Thought Police are coming for us from both sides of the aisle. It’s the kind of rote, moral didacticism you might expect from a writer like Packer, but the excerpt that Clark posted

- review • July 23, 2019

Because whiteness is a social and historical and imaginary phenomenon, not a visible, verifiable set of qualities, those of us who live in a profoundly racialized society like the United States acquire a racial awareness largely through stories, indirectly, through implication and absorption, long before we start naming names. Whiteness stands at the center of our power structure, associated with control, authority, and violence, and thus this automatic, almost autonomic recognition is often a matter of survival. So many American stories about whiteness begin here: I am safe, or I am in danger.

- review • March 28, 2019

Beyoncé Knowles-Carter makes perfect pop songs that also lend themselves to nuanced discussion of race, gender, sexuality, class, feminism, social justice, and so much more. For the past decade, I have incorporated her music into my women and gender studies curriculum. In class, I pair her songs and music videos with writing by black women from throughout US history, honoring and centering their voices. This often leads to fun, memorable, and academically rigorous conversations about Queen Bey that also celebrate the history of black feminism—and challenge the overrepresentation of white male perspectives. (This includes my own: as a white male

- review • February 10, 2019

I’m not the first, and certainly won’t be the last, person to unhelpfully ask, “Why doesn’t anyone write letters anymore?” Some of the best and most interesting writing has been done for an audience of one, without pretension. Letters are intentional but rarely contain the guile of the novel or tact of a published essay. Nobody’s posing or at least not very well.

- review • November 14, 2018

With Amélie Nothomb’s latest, Strike Your Heart, the Francophone author of twenty-five books seems to have finally found some of the American attention she deserves. (I’m basing this assessment in part on the displays of almost every New York City bookstore’s front table.) Europeans have long been wild about Nothomb: The king of Belgium named her a baroness, she’s won several of the continent’s most respected literary prizes, and articles from overseas claim that fellow Parisians treat her like a celebrity whenever she ventures out in public. She is prolific, with a precise and distinctive voice that never fails to

- review • June 1, 2018

During the last presidential election cycle, you may have read reports describing the alt-right—a loosely organized group of anti-PC, anti-feminist, race-obsessed online warriors—as a strange, newly created beast. But in many ways, the movement is simply a continuation of dark trends that have long been present in American society.

- review • February 6, 2018

It is easy to view the vast and varied landscape of marriage in the present day as a radical departure from a more conservative past. But many of these marriage alternatives—including polyamory, open relationships, and the rejection of marriage altogether—have existed for as long as marriage has. In some cases, we appear downright quaint when compared to our predecessors. Models for non-traditional coupling have long been found in fiction and nonfiction alike. Ultimately, the question of who to marry and how—or if at all—is a question of how to live. We’ve been tinkering with the answer for ages, with no

- review • December 1, 2017

During the last election cycle, the American working class got a lot of airplay. Donald Trump’s rhetoric was a throwback to a different era of politics and a different economy. Talk of American workers often included overt and coded criticism of China, which was portrayed as a villainous and devious nation that had stolen jobs from deserving Americans. Of course, the Asian workers (many of whom are not Chinese) who were supposedly responsible for America’s declining fortunes were never mentioned.

- review • November 20, 2017

[Editor’s note: This article originally appeared in 2009.] The Manson Family has been plumbed and probed inside out and upside down—there’s Joan Didion’s The White Album, Jerzy Kosinski’s Blind Date (Kosinski narrowly missed becoming a sixth victim at the Tate-Polanski residence), and more recently Zachary Lazar’s Bobby Beausoleil–driven Sway. These books compliment Helter Skelter, Vincent Bugliosi and Curt Gentry’s best-selling classic of true crime. You’ve no doubt read these, but here are a few other titles that any Manson syllabus should contain. Will You Die for Me? by Tex Watson (as told to Chaplain Ray), Child of Satan, Child of

- review • September 8, 2017

Rock criticism has long been kind to a certain species of (male) character: wannabe experts who are prone to ranting and/or raving and proudly displaying their knowledge of niche subjects. It’s hard to think of an analogous stereotype for women critics, a fact that points to the historical lack of opportunity for women in this area as well as the diversity of hard-to-pin-down work that standout writers like Ellen Willis, Ann Powers, Daphne Brooks, and Jessica Hopper have produced.

- review • June 29, 2017

In the Chinese literary world, speculative fiction has long been a necessary means of critique and protest against an overbearing regime. Science fiction authors create new (often dystopian) universes as one of the few ways to criticize the government and contend with the legacy of the cultural revolution. In China, the state presides over most of the publishing houses, so when writers want to explore forbidden ideas about progress, humanity, and the balance between individuality and the greater good, it’s often safer to package them in the guise of speculative fiction. Still, the authors’ critiques of contemporary Chinese society are

- review • June 7, 2017

Whether or not you consider yourself a gamer, video games have probably found their way into your life. Maybe you spend hours lining up gemstones, hypnotized on your daily commute. Or perhaps you roam the streets, scanning the landscape with your phone and searching for pocket-sized monsters; or live a second life, work a second job, and loyally tend your Facebook farm. Players love these games, but critics have struggled with how best to examine them, partially because video games defy categorization. They often have filmic elements such as mise en scene, a soundtrack, and a classic narrative arc. But