Brendan Boyle

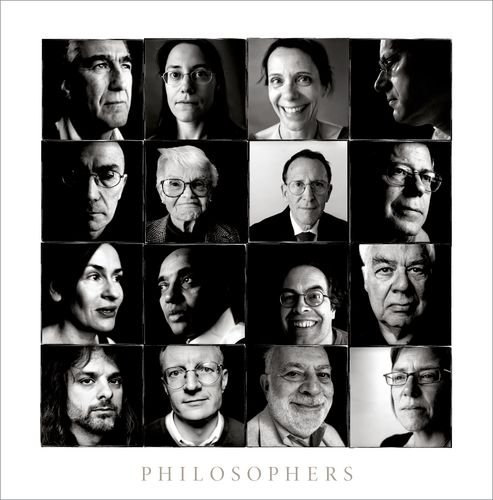

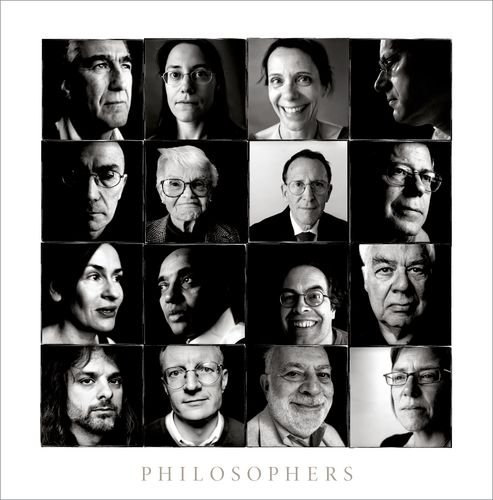

While Steve Pyke’s early photographs of philosophers featured white backgrounds, this latest collection favors a black backdrop, a decision that sets Arthur C. Danto, in an otherwise fine introduction, astir: “I prefer the black. The faces and figures are shown against the white but emerge from the black. . . . It heightens the sense that the philosophers here make an appearance from another space and luminously hover in the viewer’s space.” What fun would Richard Rorty have had with that gaseous bombast, which hails the philosopher as if from some supernatural realm. In Rorty’s absence, however, Pyke’s fine volume “Comes over one an absolute necessity to move.” And yet most times one does not. I was myself not moving—though the desire was there—when I met this sentence, the first in D. H. Lawrence’s Sea and Sardinia. In my case, moving meant reviewing The Thief of Time, not moving meant reading Geoff Dyer’s Out of Sheer Rage, a book about the “serious business of putting off writing my study of [D.H. Lawrence].” And so it began, putting off writing by reading about putting off writing, all with a familiar irritation and indignation. Upon accepting the Georg-Büchner-Prize for German literature in 1960, the poet Paul Celan gave a speech titled “The Meridian.” Celan was not given to clarity in his verse, and “The Meridian” is no different. It is, however, the best account we have of what Celan was up to in his art. An essay about the speech sits at the center of Raymond Geuss’s terrific collection Politics and the Imagination and might well hint at what Geuss, professor of philosophy at Cambridge, is himself up to.