Christopher Sorrentino

As an occupation perceived to be perpetually on the brink of obsolescence, reading has to have one of the most esteemed reputations of any human activity. We are encouraged to think of it as a virtue in itself: Entire cities are urged to simultaneously read the same book; the demise of a single bookstore inspires heartfelt tributes from those inclined to conflate poorly conceived small-business models with intellectual nobility; it is said to bind communities at the same time as it is said to free the mind. Reading has been pondered by writers from Francis Bacon to Maurice Blanchot; the

When I was asked to review Jonathan Franzen’s new novel, Purity, I happened to be in the middle of Timothy Aubry’s Reading as Therapy: What Contemporary Fiction Does for Middle-Class Americans (2011). Aubry argues that middle-class readers “choose books that will offer strategies for . . . understanding, and managing their personal problems,” explore “the psychological interior,” and present familiar characters and conflicts that validate and confirm “their sense of themselves as deep, complicated . . . human beings.” Above all, they avoid “difficult” books that compel them “to question either the value of the book or their own intelligence.” Beatles enthusiasts, like Dylan fans, seem especially susceptible to what could be called Mystical Completism—the belief that each newly discovered document, each unpublished photo, each additional outtake, represents another step along the path to ultimate enlightenment. As a pursuit, it acknowledges the forest—the variety of approaches from which the band’s chroniclers have come at their boundless subject—but much prefers the trees, those excavated documents and outtakes, over the critical or purely metaphysical.

Looming in the background of Hari Kunzru’s novel Gods Without Men are the Pinnacle Rocks, presumably modeled on California’s Trona Pinnacles, stone formations climbing from the bed of a dry lake in Death Valley and familiar to both hikers and couch potatoes (the spires regularly appear in television programs and car commercials). From its encampment near the site, Gods Without Men sweeps back and forth through time—from the deliberately anachronistic “time when the animals were men” to the present day, coming to rest at several points in the eighteenth, nineteenth, and twentieth centuries.

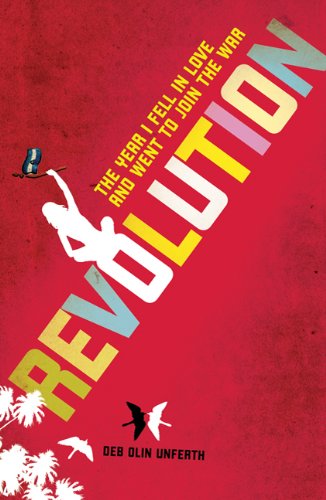

Deb Olin Unferth’s new memoir of travel and political unrest doesn’t make you wait long to discover how her sojourn works out. Revolution, which tells how in 1987 she and her boyfriend George left college and the United States to travel to Central America and “join the revolution” (actually, any revolution), begins with a brief chapter entitled “McDonald’s,” the restaurant for which Unferth makes a beeline upon returning to the US. “I was thinking about how I already knew what the food I ordered would look like,” she writes. “I knew what the French fries would look like, what the Among the aftereffects of 9/11 has been the institutionalization of a new and radically different kind of fear, far more encompassing in its reach than the old fears (of drugs, gangs, black parolees, feminists) cynically evoked by politicians and the media. In its fluent persuasiveness—you have to accept at least the possibility of another attack—fear of terrorism puts otherwise quite rational people at odds with their long-held convictions and better judgment, and it justifies the distrust and hatred of foreigners and immigration, unfamiliar religious beliefs, due process, and, generally, liberalism. John Barth once likened postmodernism to tying a necktie simultaneous with providing a detailed explanation of the procedure while also discussing the history of neckties and still ending up with a perfect Windsor knot. It’s an entirely credible definition of the concept—some days I’d happily accept it in exchange for the whole of my small library on the subject—and charming, too. Barth’s always been a charmer, although at nearly eighty years old he’s more like the lovable old uncle who’s been entertaining the kids with that necktie routine for about fifty years than the onetime vigorous advocate for “passionate virtuosity.”