Fiona Maazel

IT’S NEVER BEEN A GOOD TIME to be anything other than a white cis male in this country. From there, we might debate which identities and preferences are the most persecuted but can probably agree that now is an especially terrible time for anything that’s not the muscled, racist, and American brand of, say, Joe […]

NOT TO MAKE THIS review about me or anything, but about ten years ago I published a big book with multiple characters and story lines. My dad, then in his seventies, said I should have included a character list and roadmap because he had trouble following it all. I remember thinking, in response, that he’d obviously gotten old and slow and that his tastes were conservative and fuddy duddy. Today, I’m willing to concede I might have turned into this same fuddy-duddy, which I offer up as context for my thoughts on Ed Park’s—what is the right adjective here? discursive? fascinating?

REMEMBER WHEN THE worst thing was death? AIDS, cancer, COVID—a horror for the people who died (are still dying) and a massive source of anxiety for the rest of us. And yet as my daughter and I waited out lockdown—fwiw, my daughter in this context represents the zeitgeist—she never once worried about us dying from COVID. Nope, she’d already assimilated death anxiety into her shelf of bedtime reading, the old standards. Instead, her fear had stepped up and out on a ledge overlooking apocalypse. Climate change. The end of everything. Extinction.

Fifty pages into this novel—Susan Choi’s fifth—I was ready to write about it. I understood its design and I admired its execution. So let’s just start there—with what I knew. Two fifteen-year-olds, Sarah and David, attend a prestigious arts school, the Citywide Academy for the Performing Arts (CAPA). Neither can drive, but both can have sex. They fall in love, though this is probably not the right word for what they experience. Their love is colossal. Monstrous. Steamy and feral. They are kids entrained by desire into appearing older and more savvy than they are.

I’ve heard it argued—and I agree—that fiction that builds a universe whose rules depart from our own allows for the contemplation of ethical dilemmas that cannot be addressed in or by the world as we know it. This kind of fiction—what my toddler might call “same but different”—tends to disrupt our go-to feelings. In an alternate universe, you are moved to relitigate the basics because you cannot take anything for granted. The sun is black; the moon is pink; everything we know needs to be reevaluated—the facts of our lives and, by extension, the principles we hold dear. Similarly, fiction

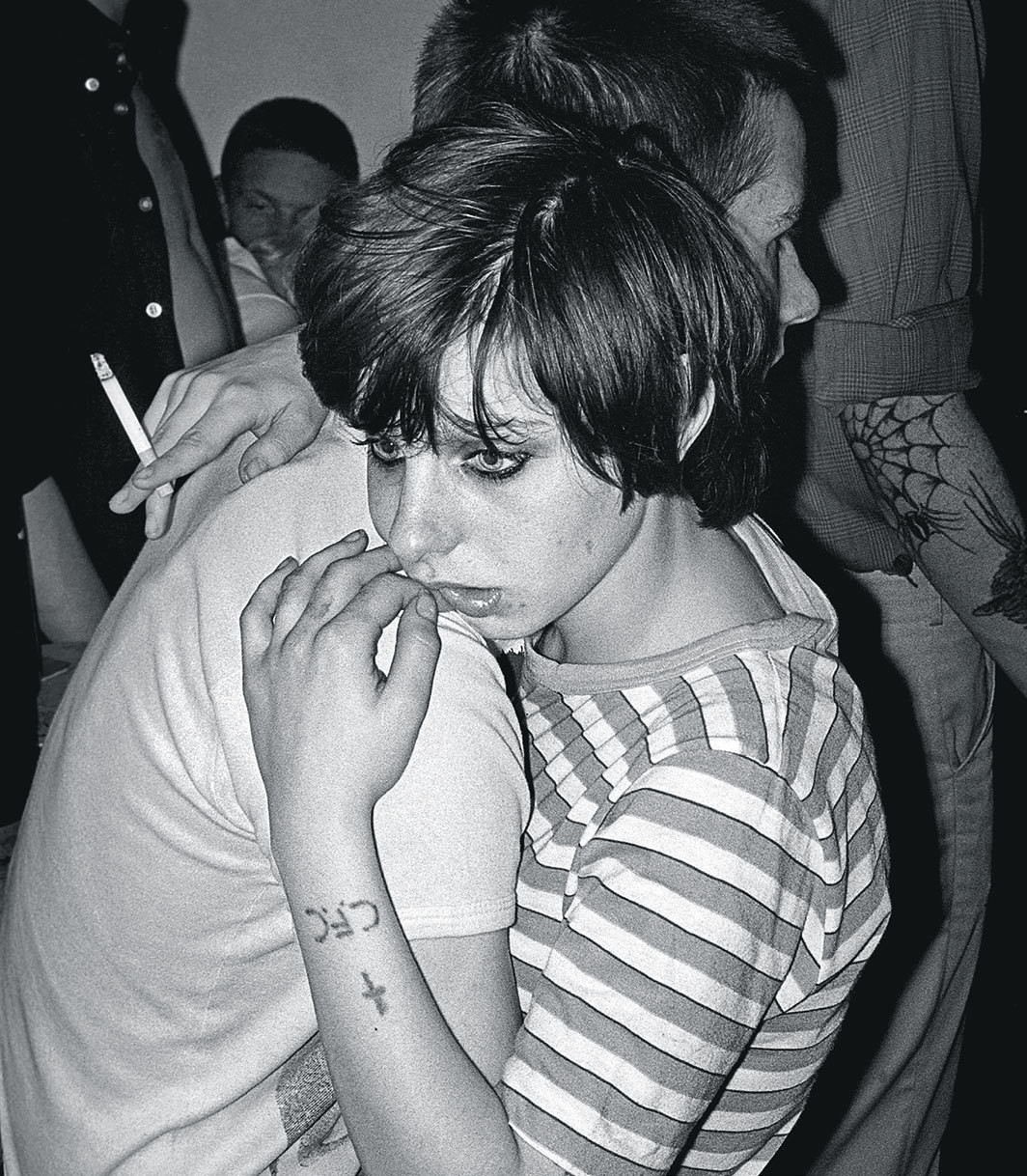

The writer Barry Hannah used to say that even though Bob Dylan can’t sing, he has the desperation of not being able to sing, which is better than being Glen Campbell, who can sing. Of course, there’s something patronizing here: Even if Dylan can’t sing, he can do a lot of other things well. And anyway, he can sing. Just not like your average crooner. In False Positives and False Negatives (8), 2012, artists Jane and Louise Wilson show one way to maintain anonymity in a surveillance state: by using face paint. By now, chances are good you’ve read a thing or two about Dave Eggers’s The Circle. There’s been some controversy about plagiarism (as if there’s no way two […]