Frances Richard

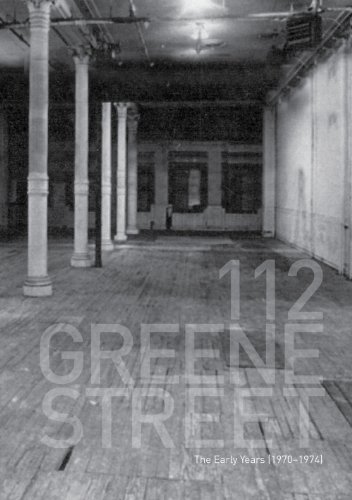

“It is rather inspiring,” writes Peter Schjeldahl in the New York Times, “that in an hour of political crisis this art (despite its makers’ eschewal of revolutionary postures) has arisen to make possible a project like 112 Greene Street.” The year is 1970. The place is Soho, until recently known as the South Houston Industrial District. Here an unemployed artist can buy a six-story cast-iron ex-rag-picking warehouse, and huge chunks of sheet-zinc cornice can lie abandoned on the sidewalk at a demolition site until another artist bribes the garbage men to drive them to his studio. Sculptor Jeffrey Lew owns “Many people answer with ‘Yes, but . . .’” wrote Marcel Duchamp in 1954, in a tribute to his great friend Picabia, who had died the year before. “With Francis it was always: ‘No, because . . .’” Inventor of the “machinist painting” and carrier of the Dada virus to New York and Paris, Picabia was editor of the journal 391 and author of numerous books of poetry and prose, along with manifestos, aphorisms, and scenarios for ballets and films. He impressed everyone who met him with a cocksure nihilism. “Anybody called Francis is elegant, unbalanced, and intelligent,” Gertrude Stein The intergenre artist Theresa Hak Kyung Cha made her reputation with the experimental novel Dictée, published in 1982, a few days after she was murdered by a stranger in New York. A speculative history of Korea as it intersects with the life of Cha’s mother, Dictée intercuts oneiric prose with family photographs and political documents. English, French, and Korean shape the book’s voices.