Hannah Zeavin

DURING THE SECOND WORLD WAR, D. W. Winnicott worked on the adolescent unit of the Paddington Green Children’s Hospital. There, just beyond Hyde Park in the center of London—under threat of constant bombing—Winnicott would make his rounds, asking all his patients the same question: “What do you want to be when you grow up?” Asking […] AARON BUSHNELL WAS a twenty-five-year-old active Air Force member, employed as a cybersecurity expert. After growing up in a conservative religious sect on Cape Cod, he joined the US military a few years after Donald Trump was elected. Soon after George Floyd was murdered, Bushnell had a political awakening, became critical of the military, and started participating in mutual-aid projects. An autodidact who eventually identified as an anarchist, Bushnell moved from San Antonio to Ohio, where he prepared to transition out of the military. You likely know how his story ended: on Sunday, February 25, 2024, he died by self-immolation outside

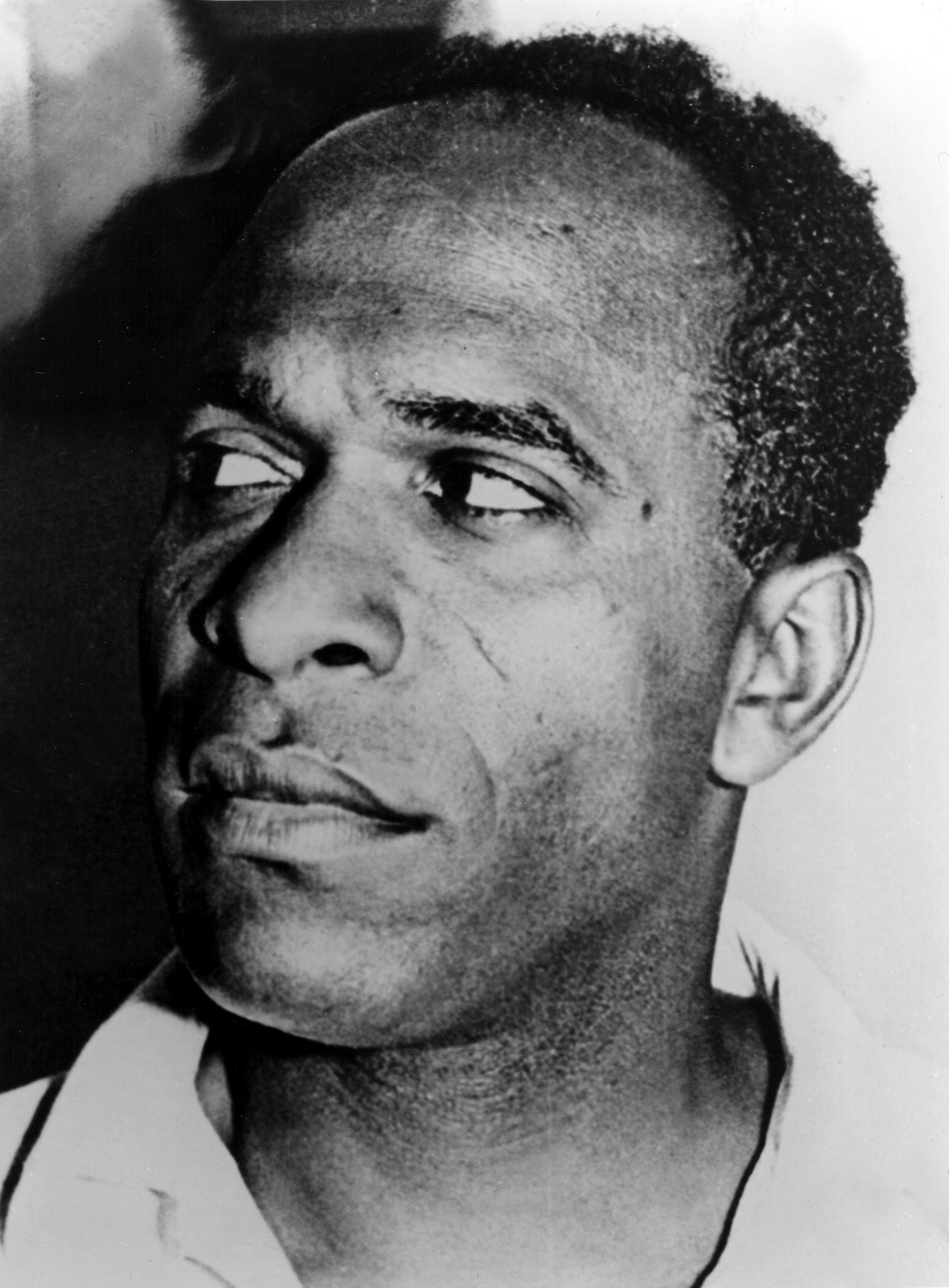

Adam Shatz and I met recently to speak about his latest book, The Rebel’s Clinic: The Revolutionary Lives of Frantz Fanon (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, $32). Fanon was a psychiatrist and anti-colonial theorist. Born in Martinique in 1925, he trained as a psychiatrist in France before he became the director of a psychiatric hospital in Blida, Algeria. There, he began to work with the National Liberation Front (FLN) and later went into exile in Tunisia. Fanon died at the age of thirty-six in Bethesda, Maryland, after receiving delayed treatment for leukemia at the National Institutes of Health—arranged for by the CIA.

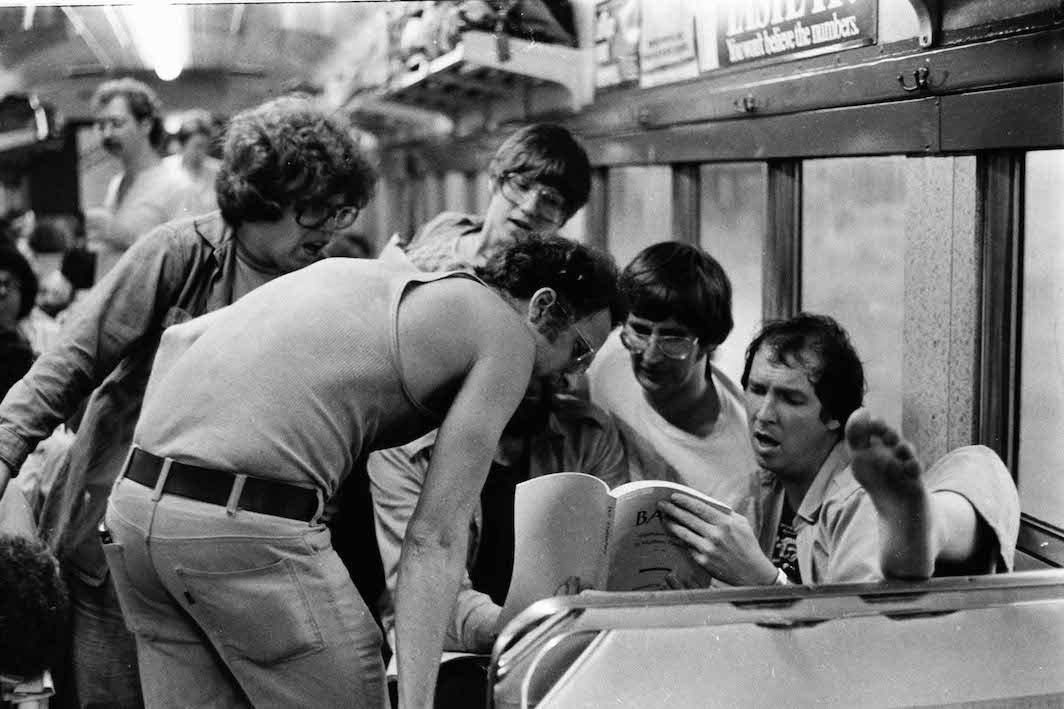

IN THE SULLIVANIANS: SEX, PSYCHOTHERAPY, AND THE WILD LIFE OF AN AMERICAN COMMUNE, journalist Alexander Stille follows whispers of a psychoanalytic cult and breaks open the story of how psychotherapy escaped the consulting room and became the total environment of its patients. The book centers on Saul Newton, a therapist turned charismatic leader who directed a collective search for liberation through analysis and communal living. Needless to say, it all went horribly wrong.

THE PUNCH LINE OF ACADEMIC THEORY IS A REDESCRIPTION OF THE THING WE ALREADY KNOW, so that we might know it once more, with feeling. In Lauren Berlant’s words, heuristics don’t start revolutions, but “they do spark blocks that are inconvenient to a thing’s reproduction.” Berlant’s new book, On the Inconvenience of Other People, arriving just a little over a year after their death, is a study in just that. Inconvenience serves as a sequel of sorts to Cruel Optimism (2011), the work that guaranteed Berlant’s fame beyond the academy. Berlant, the literary scholar of national sentiment, affect, the ordinary