Kaitlin Phillips

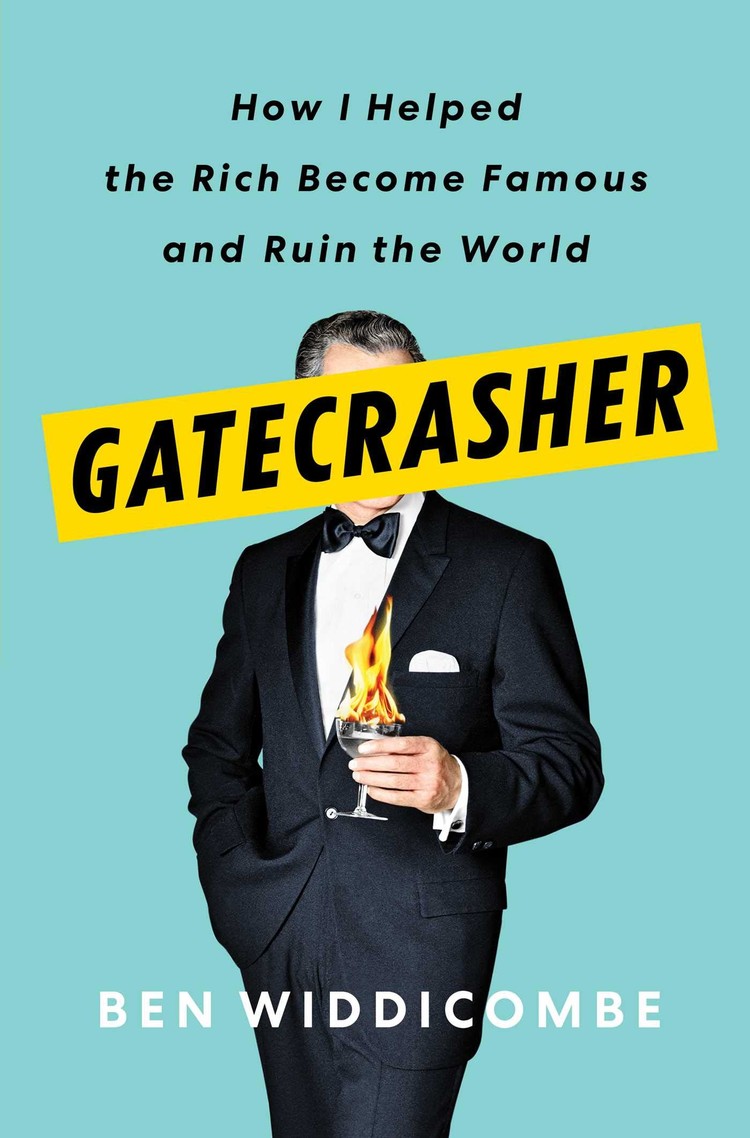

IF CRAFTING THE PERFECT seating arrangements is a delicate art for blue bloods—and vandalism is the opposite of art, as well as a pastime for talented poor people—then it follows that party reporting, at its most refined, is a form of controlled demolition on private property. In their heyday, party reporters were a bit like graffiti artists on the Upper East Side, tagging the marble walls (“Slut!” “Bankrupt!”) as fast as they can be cleaned up. What is a personal publicist but an overpaid janitor with a pressurized hose?

The best pieces of long-form journalism are those where you get the sinking feeling the subject has no idea what the point of journalism is. No inkling that a salacious story is better than a puff piece. No fundamental understanding that a writer, at the end of the day, is only going to make her career if she exploits her subjects, even if it’s just to expose their bad personalities or unkempt apartments. It thrills to read a story that no one wants written about themselves. Whether you are party reporting or writing profiles, you can always find something unethical

Unlike television—where every profession is indicated through props, like a cup from Starbucks—novels often let their characters do the work. Work is a fount of material, what with the complaining, cheating, procrastinating, backbiting, tedium. Not working too. Being unemployed is taxing! Every novel about a rich person who doesn’t work could be marketed with the tagline Everybody works. And who can argue with that? Not a writer.

The concept of “literary lions” seems antiquated in a world that doesn’t want writers as public intellectuals. We don’t turn on the TV to learn anything, certainly not from a writer on national news. Even less plausible is an ecosystem that allows a magazine editor to “reign” at a publication, entwining her identity with its output to the extent that the brands are interchangeable. Upon the deaths of George Plimpton, Barbara Epstein, and Bob Silvers, the identities of the Paris Review and the New York Review of Books were naturally diluted somewhat, like a glass of whiskey served only after

When Jenny Offill’s Dept. of Speculation came out in 2014, I couldn’t elbow my way to the bar without having a conversation with a woman writer about whether or not we knew any art monsters. Ottessa Moshfegh? Even Kate Zambreno and Joy Williams have children. . . . It seemed fitting we were all suddenly preoccupied with this question, as if we’d found a way to talk about whether or not we wanted to be geniuses, like the men.

The index card pinned to an unassuming bulletin board is catnip for lonely women with bad day jobs—the types who spend late nights at AA meetings in church basements and do their own wash-and-fold in sticky, twenty-four-hour laundromats. Listless and desperate for change, bored in depressing, utilitarian cityspaces, they try contacting a stranger.

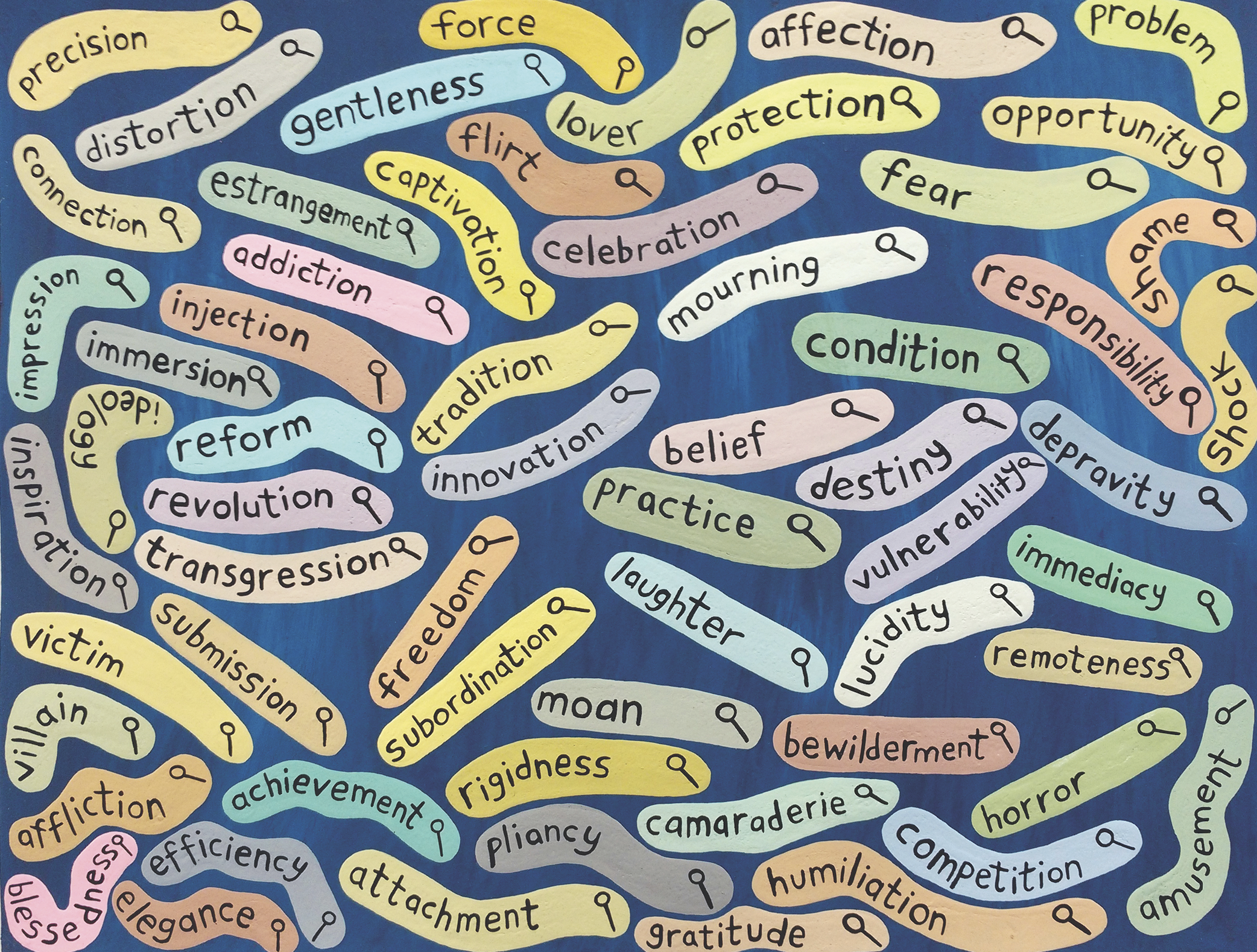

Cat Marnell—the popular drug-addicted beauty editor and blogger—has written the kind of ’90s-era junkie memoir that lends itself to the morbid curiosity we reserve for anyone who dies before we discover their work. Like Anna Kavan, a lifelong imbiber of heroin, Marnell published her first piece of writing as an addict. (When Kavan died, her friends found forty different shades of lipstick in her apartment.) Marnell’s story does not veer into the kind of self-mythologizing that occasions armchair fact-checking. In fact, it’s a departure from a career spent transmogrifying her troubles for an eager audience.

I know three people microdosing LSD or mushrooms: a very young, pearly-cheeked web editor from California; a wealthy, jarringly enthusiastic computer programmer I met at a warehouse party; and a catalogue model with a demure husband. Like everyone, they appear happier and more productive than me. They work in midtown. They live in better neighborhoods in Brooklyn. Their existence does not, however, propel me to alter my consciousness, much as a low-level aversion to scientific nonfiction from independent publishers will forever keep me from reading the book that “popularized” microdosing: The Psychedelic Explorer’s Guide: Safe, Therapeutic, and Sacred Journeys (2011), Tama Janowitz’s Slaves of New York (1986)—the occasionally brilliant but ultimately uneven collection of twenty-two stories she wrote between the ages of twenty-three and twenty-eight—sowed her literary reputation as the lone woman in the “literary Brat Pack.” In fact she shared little with McInerney and Ellis that wasn’t cosmetic: youth, the 1980s, and a tendency to write about conspicuous consumerism in a way that made realism read like satire and vice versa (this wasn’t a trait unique to the Brat Pack—The Bonfire of the Vanities was published in 1987). The book party for Slaves spawned a New York magazine cover

“I had a prescription for a low-milligram antianxiety medication, as well as a mild beta blocker,” a man explains in Amie Barrodale’s icy, masterful first short-story collection, You Are Having a Good Time (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, $14), “and I kept going into the bathroom to take more—I wanted to get the mixture right. After I took a pill, I’d check myself in the mirror, and I’d always be surprised at what I found. I kept expecting to find a monster.” It’s almost uncivilized how precisely Barrodale renders life as a banal grotesquerie in which you have the wherewithal to