Kera Bolonik

John Irving always starts his stories at the end, which is why it has taken him nearly twenty years to write his twelfth novel, Last Night in Twisted River (Random House, $28). “The ending just eluded me,” he said in late September, when he spoke to me by phone from his Vermont home. “I knew only that there was a cook and his son, in a rough kind of place, and something happens to make them fugitives.” The protagonists in this exquisitely crafted, elliptically structured novel—a gripping story that spans five decades and extends across northern New England and

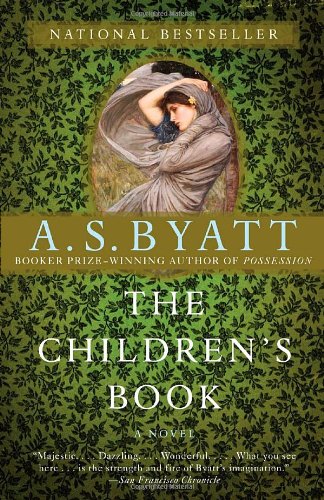

The prolific A. S. Byatt has been publishing novels since the mid-’60s (her first, The Shadow of the Sun, came out in 1964), but it wasn’t until 1990, when she won the Booker Prize for Possession—the story of a pair of contemporary scholars whose research on two Victorian poets reveals an extramarital affair between them—that she became an international (literary) household name. But Dame Byatt, who was awarded the DBE ten years ago (and the CBE nine years earlier), credits not the Booker Prize but the Web with her considerably raised profile: “Everything I say or write is now John Irving always starts his stories at the end, which is why it has taken him nearly twenty years to write his twelfth novel, Last Night in Twisted River (Random House, $28). “The ending just eluded me,” he said in late September, when he spoke to me by phone from his Vermont home. “I knew only that there was a cook and his son, in a rough kind of place, and something happens to make them fugitives.” The protagonists in this exquisitely crafted, elliptically structured novel—a gripping story that spans five decades and extends across northern New England and Ontario—are The prolific A. S. Byatt has been publishing novels since the mid-’60s (her first, The Shadow of the Sun, came out in 1964), but it wasn’t until 1990, when she won the Booker Prize for Possession—the story of a pair of contemporary scholars whose research on two Victorian poets reveals an extramarital affair between them—that she became an international (literary) household name. But Dame Byatt, who was awarded the DBE ten years ago (and the CBE nine years earlier), credits not the Booker Prize but the Web with her considerably raised profile: “Everything I say or write is now perpetuated Aleksandar Hemon does not write for, in his words, “therapeutic reasons.” But as the virtuosic author told me over a southern-fried lunch in Chicago one cold, damp March afternoon, writing has unexpectedly helped him fuse his two lives: At twenty-eight, in the spring of 1992, he became stranded in Chicago during a month-long journalism program, when his home, Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, fell under siege and was ravaged by civil war. In just a few years, Hemon was publishing stories written in English, which he perfected by reading Nabokov and canvassing door-to-door for Greenpeace. Hemon, a MacArthur “genius,” has since F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Tender Is the Night served as a muse for Geoff Dyer’s last work of fiction, Paris, Trance (1998), but the author admits that Thomas Mann’s Death in Venice, the inspiration for his latest effort, Jeff in Venice, Death in Varanasi (Pantheon, $24), never held much meaning for him. “It’s one of those books that’s part of the mythic template,” the award-winning essayist and consummate enthusiast, who has written on such wide-ranging subjects as photography, D. H. Lawrence, and World War I, explained to me on the phone while he was snowbound in London one February morning. Dyer Mary Gaitskill defies definition. In fact, during our conversations about her extraordinary story collection Don’t Cry (Pantheon, $24)—her fifth book, following her multi-award-nominated 2005 novel, Veronica—she told me so. Gaitskill’s candor is just one of the virtues I find beguiling about her and her fiction. How else but with honesty and an unflinching eye could she portray the often-disturbing interior and exterior lives of the people who appear in her pages, like the grief-stricken Texas nurse haunted by a dream of two men locked in murderous battle following a game of pickup basketball, and the Iraq-war veteran bearing witness to David Rhodes was still a student at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop in 1971 when Atlantic–Little, Brown editor Joseph Kanon bought his first novel, The Last Fair Deal Going Down, a fantastical, dark tale of two Iowa cities, launching a prolific literary career. Two more novels appeared in quick succession: The Easter House (1974), which earned Rhodes comparisons to Sherwood Anderson, and Rock Island Line (1975), which John Gardner cited as an exemplar of the form in On Becoming a Novelist. In 1972, the writer settled into a quiet life in a century-old farmhouse in the southern Wisconsin town of Wonewoc Irish writer Anne Enright has won literary awards for nearly every book she’s published since her debut in 1991, the short-story collection The Portable Virgin (which earned her the Rooney Prize for Irish Literature). But for over a decade, the onetime television producer, who studied creative writing with Angela Carter and Malcolm Bradbury, lurked under readers’ radars. She prolifically published fiction that sometimes veers into the fantastic realm of her mentors—The Wig My Father Wore (2001), for example, features the angel of a man who killed himself many years earlier. Then, last year, she was awarded the Man Booker Prize