Lincoln Michel

Around the turn of the millennium, Sam Lipsyte was an almost secret writer who inspired obsessive admiration. I had started to write fiction then, and my fellow aspiring writers and I would share Lipsyte rarities—a story in a back issue of Open City or NOON, a well-worn copy of his debut story collection Venus Drive (2000) or The Subject Steve (2001)—like pre-internet punk rockers trading tape dubs of out-of-print 7-inches. He’s not so secret anymore, particularly since his critically acclaimed novel The Ask (2010), but his work continues to generate a rare sense of excitement among the writers and

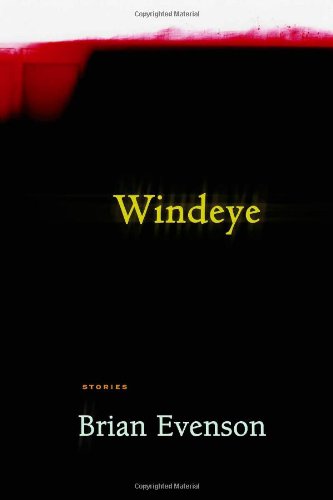

Bookstores, libraries, and in some cases writers themselves have long treated “genre” and “literary” fiction as separate categories that belong on separate shelves. Brian Evenson, whose dark and masterful fiction has been published by both literary and genre presses, is a writer who exposes the limitations of this distinction. Genres are important to the degree that they offer frameworks for writers to participate in and draw strength from. They are, however, only one way of grouping literature. Another way is to think about the effects that a work produces. If there is one thing that unites Evenson’s work in Windeye—his The Bush administration sold us a war based on phony intelligence; Bernie Madoff sold investors invisible stocks. The art of peddling snake oil may be age-old, but something about the deceit of recent years makes Clancy Martin’s debut novel, How to Sell, feel very timely. Set amid the Fort Worth jewelry trade, this drug-fueled coming-of-age tale knowingly explores our culture of greed and excess.