Marco Roth

AMONG THE MANY ENTRIES in Edwin Frank’s increasingly encyclopedic New York Review Books Classics series is a genre of postwar European memoir: informed by psychoanalysis, ironic in tone or form, and of subject matter that’s both bourgeois and aristocratic—or at the intersections where upwardly moving middle classes and downwardly mobile inherited scions most resemble each other. Gregor von Rezzori’s Memoirs of an Anti-Semite, J. R. Ackerley’s My Father and Myself, Jessica Mitford’s Hons and Rebels: these books record their authors’ efforts to collect the pieces and resolve mysteries of their childhoods and adolescence—a task often complicated by the shattering impact

A few months ago, the thirtieth-anniversary republication of a book written at the peak of the HIV epidemic and chronicling the impact of the virus on an intimate social circle of French writers, artists, medical professionals, and intellectuals—Michel Foucault among them—might have been a boutique or scholarly curiosity. AIDS, after all, has become one of the few medical and socio-biological “success” stories of recent decades. Testing plus an effective cocktail of antiretroviral drugs, alongside newer prophylactic treatments like Truvada, has reduced the illness to a chronic condition rather than a death sentence. In so-called advanced nations, the disease is mostly

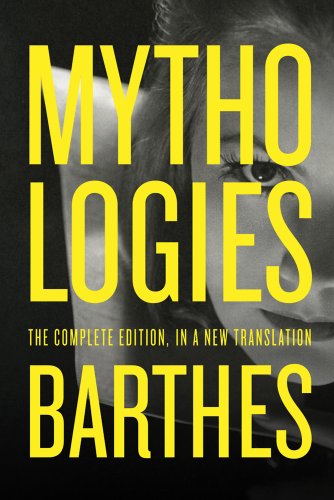

Perhaps the best way to understand what drove Roland Barthes, then a thirty-nine-year-old professor of literature, to begin writing the series of short essays later published as “Mythologies” is to take a brief glance at the myth of the supposedly decadent influence of French theory on American intellectual life.