Nathan Goldman

LAST DECEMBER, nestled amid the second and final COVID-19 stimulus package of Donald Trump’s presidency was a strange provision: within 180 days, the Secretary of Defense and the Office of the Director of National Intelligence were to release an unclassified report detailing the agencies’ knowledge about unidentified flying objects. Between the law’s passage and the release of the report, American interest in UFOs—or, as government officials have euphemistically dubbed them, “unidentified aerial phenomena” (UAP)—soared. In May, 60 Minutes ran a segment featuring witnesses, including two Navy pilots, who had observed these mysterious entities. Barack Obama confirmed their existence. The report,

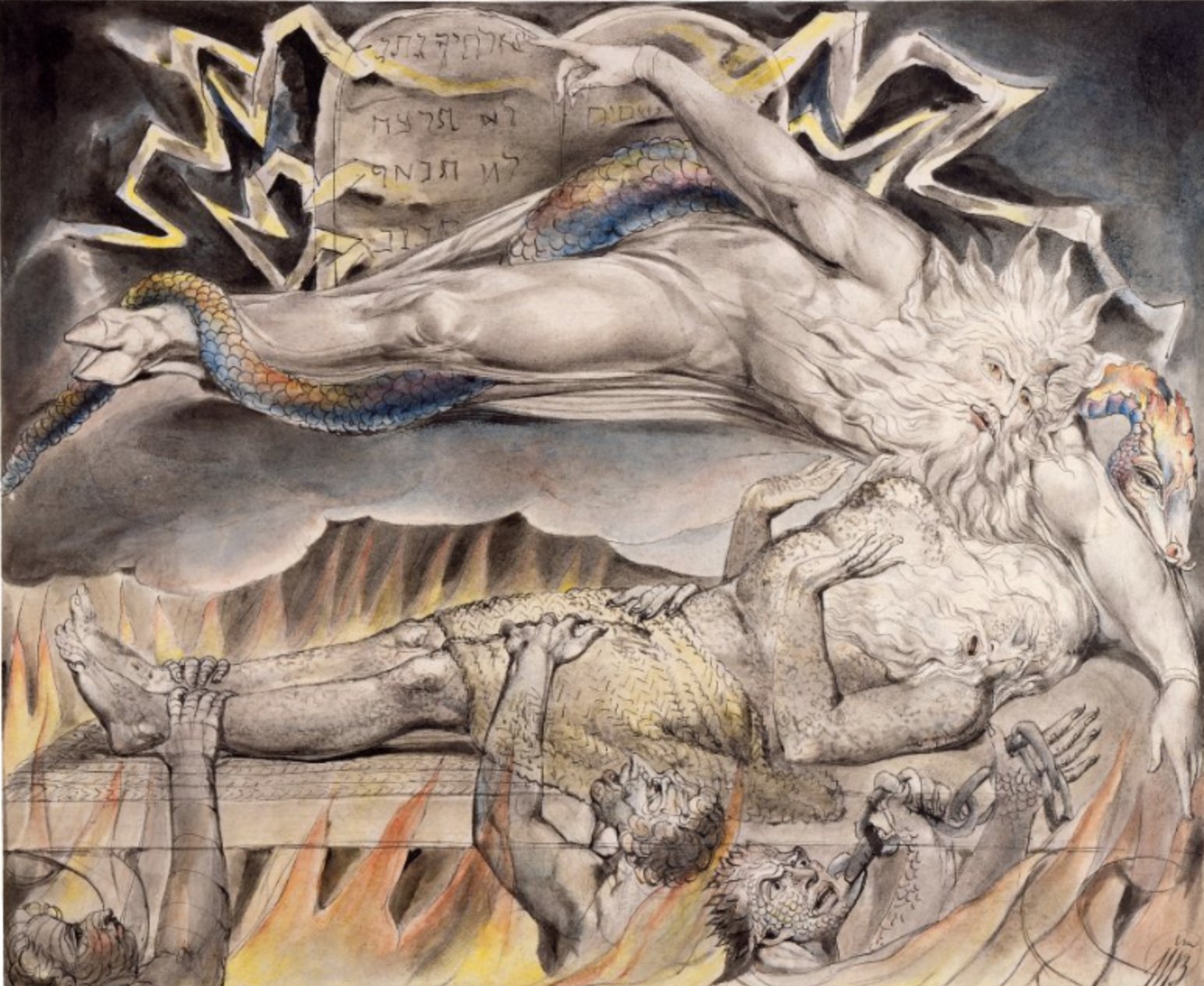

The pivotal moment of the book of Job occurs in its final chapter. Job, the paradigm of piety—God-fearing and evil-shunning, as he’s introduced in the book’s first lines—has, despite his moral uprightness, suffered profoundly. He has endured the deaths of his ten children; an excruciating, all-consuming skin disease; and haranguing by four friends who have insisted, relentlessly, that God wouldn’t torture Job without just cause, despite his repeated insistence that he has done nothing to deserve his fate. In response to Job’s pleas for answers, God himself has spoken to him from a whirlwind. Job’s anguish, the text’s prose frame

What is color to literature? For one thing, a problem. Language deals in delineation. This makes it an odd match to account for color—an abstract, pure vividness—which, on its own, has no differentiating power at all. At the same time, without color, visual differentiation becomes difficult. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, in the introduction to his 1810 Theory of Colours, wrote that “the eye sees no form, inasmuch as light, shade, and colour together constitute that which to our vision distinguishes object from object.”