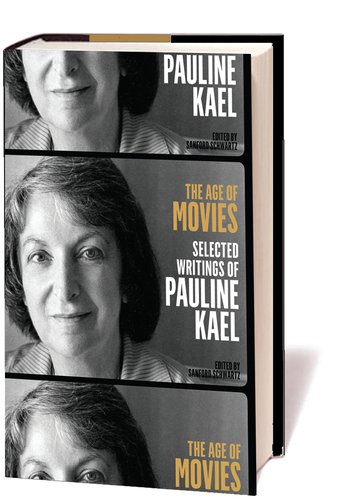

Nathan Heller

In the fall of 1965, a season that brought movies as distinct as “Alphaville” and “Thunderball” to the screen, Pauline Kael came to dinner at Sidney Lumet’s apartment, in New York. Lumet was then a prolific young director, having just finished shooting his tenth feature, “The Group,” for United Artists. Kael was a small-time movie critic who had recently arrived from Northern California. Her hardcover début, “I Lost It at the Movies,” had appeared that spring, to critical and popular acclaim, but she had never been on staff at any publication, and had only recently begun to write for major The French iconoclast Guy Debord tends to be known in America—if he is known at all—for two things, both of which peaked in the student movements of 1968, when he was thirty-six. Debord was a founder of the Situationist International, an underground organization whose roots lay in Dada and cultural Marxism and whose whimsical slogans, creative defiance, and cryptic prose attracted dreamers on both sides of the pond. He was also a curmudgeon. His 1967 book, The Society of the Spectacle (the other thing he’s known for), was the high point in a lifetime of faultfinding, paranoia, and alienation. In Cahiers du cinéma—the magazine that launched the New Wave, made heroes of Hitchcock and Joseph L. Mankiewicz, and grew into a sort of beau ideal for movie criticism—rose from the belief that mainstream moviemaking was a modern art. This wasn’t an especially new idea. The magazine’s founding editors, including André Bazin and Joseph-Marie Lo Duca, were critics known already for their Hollywood affinities; Cahiers took its example from the journals they had written for. An avid cinephile who saw the first issue in 1951 would have been caught off guard less by its viewpoints (which squared nicely with those of