Suzy Hansen

In 2009 Mohamed Nasheed, the president of the Maldives, the island nation sinking into the sea, put on a wet suit and an air tank and, along with several of his ministers, held a cabinet meeting underwater. Nasheed hoped to give the world a sense of its collective future. At an event at Columbia Law School he later said: “You can drastically reduce your greenhouse gas emissions so that the seas do not rise so much. Or when we show up on your shores in our boats, you can let us in. Or when we show up on your shores

In the weeks before my departure, I spent hours explaining Turkey’s international relevance to my bored loved ones, no doubt deploying the cliché that Istanbul was the bridge between East and West. At first, my family was not exactly thrilled for me; New York had been vile enough in their minds. My brother’s reaction to the news that I won this generous fellowship was something like, “See? I told you she was going to get it,” as if it had been a threat he’d been warning the home front about. My mother asked whether this meant I didn’t want the

While reading Trita Parsi’s history of the US-Iran nuclear negotiations, it’s hard not to wonder with horror—at every complicated twist and turn of the proceedings—how Donald Trump would manage a similar ordeal. The sometimes excruciating detail of Parsi’s book reminds us of all the tiny acts of diplomacy—and anti-diplomacy—happening right this very second behind closed doors, ones that could, in the case of Iran, be leading to unnecessary war.

The wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, unique in their sophisticated weaponry and surreal nation-building aspirations, surely demand their own brand of literature, a mode of writing that will capture, somehow, the careless brutality that the world’s most powerful country wrought on two fragile populations. The striking difference between the wars of the past and those of the present is the scale of the imbalance. As one Iraqi in Anthony Shadid’s Night Draws Near told him just before the invasion, “What is Iraq? This is crazy! The United States is so powerful. It should respect itself. It should use its power

Americans who have lived abroad know that the rest of the world is mildly obsessed with the CIA. I live in Istanbul, and early on I learned that many Turks believe CIA agents can pull off everything from September 11 to the election of Islamists; what’s more, they suspect I might be a spy, too. In this view of the world, some foreign influence is always responsible for something, some outside group is always “fomenting chaos” somewhere, some lethal CIA squad is always making it look like the leftists bombed the rightists by bombing the rightists themselves. At first, to

On April 5, 1946, the USS Missouri, “the world’s most famous battleship,” sailed up the Bosporus and docked in Istanbul. President Harry Truman had dispatched his triumphant vessel to deliver the body of Turkish diplomat Münir Ertegün (the father, as it happens, of Atlantic Records founder Ahmet)—and, more important, to secure an alliance with Turkey at the beginning of the cold war. At the time, the Turks had few friends in the world. Only thirty years earlier, the British prime minister, David Lloyd George, had called the Ottomans “a human cancer.” When the victorious Americans appeared on Istanbul’s shores, the

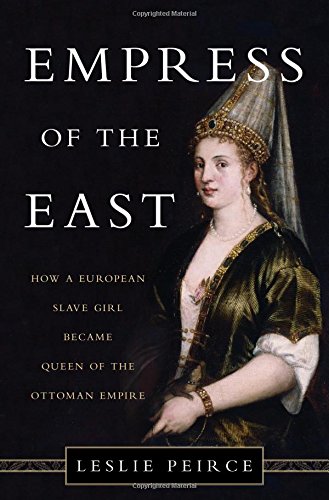

Six years ago, a soap opera set off an angry debate among historians, politicians, and viewers in Turkey. It was called Muhtes¸em Yüzyil (The Magnificent Century) and depicted the inner workings and often-violent intrigues of the sixteenth-century Ottoman palace—particularly the fraught relationships between Sultan Süleyman and his harem, viziers, and eunuchs. The show was wildly popular, but politicians from the AKP, the party of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, protested the portrayal of the holy sultan as a lush and a womanizer. They claimed it was clearly inaccurate, as if they were unaware of the Ottomans’ reputation as decadent and lusty. Erdoğan,