Victoria Baena

In his 2016 book, The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable, Amitav Ghosh argued that contemporary fiction—at least the literary, realist kind—has failed to imagine and represent our “deranged” relationship with the natural world. Science fiction, he maintains, has done a better job of critiquing our world and imagining it differently. The realist novel’s preoccupation with individual morality and everyday normalcy has left it ill-equipped for a world in which the improbable is the norm.

The novels of acclaimed French writer Marie NDiaye are set in familiar spaces: domestic worlds, often within cities. Her protagonists are usually determined, upwardly mobile women in pursuit of stability. But NDiaye’s stories also press against the boundaries of realism. If, in the nineteenth-century realist novel, family and origin provide clues about the self, here, they show the point at which the self can unravel. The strangeness, pain, and horror of relationships are indexed by odd, fantastic events in NDiaye’s otherwise lifelike storylines. In her 2016 novel Ladivine, for instance, a family arrives at an unnamed tropical country for a

In his native Argentina, César Aira no longer shocks audiences with his genre-bending works, surrealist plot twists, or the sheer pace of his output (he’s written more than eighty books as part of his fuga hacia adelante, a “flight forward”). New Directions began translating his work into English about a decade ago, and since then, most Anglophone critics have focused on on Aira’s formal inventiveness: How I Became a Nun (translated in 2007), for instance, gleefully unravels a traditional bildungsroman plot, beginning with the narrator’s faux-somber recollection of her revulsion, as a six-year-old, at the taste of strawberry ice cream.

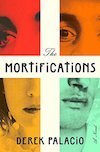

Author Derek Palacio describes his relationship to Cuba, his father’s homeland, as one of “abstraction.” Since he’s never visited the island himself, he told the Kenyon Review, “the people, culture and landscape of [my stories] are not Cuban, then, but are the offspring of my Cuban impressions.” The same might be said for the characters of Palacio’s debut novel, The Mortifications. Its protagonist, Ulises Encarnación, his twin sister, Isabel, and their mother, Soledad, flee Cuba in 1980 and return six years later. But while the island is described with vivid sensory detail, the characters’ relationships to Cuba have perhaps more