Legend has it that Eugenia Wilder nicknamed her second son “Billie” after Buffalo Bill, whose Wild West touring show she had seen as a young girl in New York City. By calling him Billie, she may have given him the idea of making his life in show business in America. Her husband, Max, an upwardly mobile restauranteur and hotelier, clearly had other plans when he moved the family from the Galician village of Sucha to Kraków before moving on to Vienna when Billie was a child. Like many Jewish fathers before and after him, it was that his son should be a lawyer. No doubt he was less than pleased when Billie, a recent graduate of a Vienna gymnasium, which had prepared him for university studies en route to his eventual legal career, became a reporter instead, hoping to make it to the United States as a foreign correspondent.

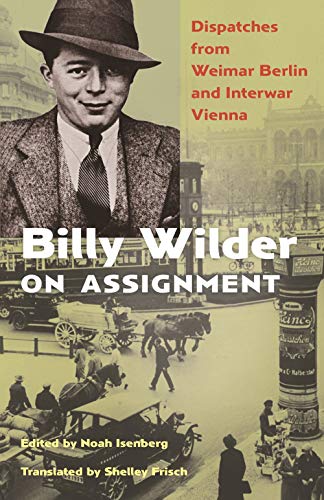

For the next decade, however, Wilder’s travels would take him primarily into the gray economies and topsy-turvy value-systems created by the new forms of capitalist mass production. In Vienna and later in Berlin, Wilder was the stringer at half a dozen publications that ran the gamut of journalistic respectability: his byline appeared in tabloids, teen magazines, daily newspapers, and highbrow journals. Billy Wilder on Assignment: Dispatches from Weimar Berlin and Interwar Vienna, a selection of these pieces, edited by Noah Isenberg and translated by Shelley Frisch, is now available in English from Princeton University Press.

Wilder’s beat was urban modernity, with its fads and dance crazes, its new gadgets and experiences, and the new kinds of people it made. He wrote capsule reviews of movies and plays, slice-of-life pieces, travel pieces, celebrity profiles, profiles of people surviving on the fringes of society, personal essays, and—most successfully, from a literary standpoint at least—the kind of informal cultural commentary known in Mitteleuropa as the feuilleton. He did everything, in short, except for serious reporting. Forty years before American New Journalism made it regular practice, Wilder placed himself—or rather, his persona “Billie”—at the center of his stories. Billie is a man on the move: a hustler, in both senses of the term, filing dispatches, in both senses of the term. His dialogue and descriptive prose are chatty and clipped, as though the accelerated pace of life in the modern metropolis (or his editor’s tight deadlines) did not permit him to linger in a conversation or a scene. He once claimed to have interviewed Sigmund Freud, but, in his writing at least, he eschews the iceberg model of the psyche in favor of the principle that clothes make the man.

In “Waiter, A Dancer, Please!” his longest piece in the collection and his best-known work of journalism, Wilder writes about his experiences working as a dancer for hire or “taxi dancer” in Berlin, a job that toed the narrow line between entertainment and sex work. This is how he describes his workplace: “In the ballroom. Packed. Cigarette haze. Perfume and brilliantine. Preened ladies from twenty to fifty. Bald heads. Mamas with prepubescent daughters. Young men with garish neckties and brightly colored spats. Whole families.” And this is how he describes the work: “I make my living honestly, honestly and with difficulty, because I dance honestly and conscientiously. No wishes, no desires, no thoughts, no opinions, no heart, no brain. All that matters here are my legs, which belong to this treadmill and on which they have to stomp, in rhythm, tirelessly, endlessly one-two, one-two, one-two.”

As for making his living honestly, the remark was surely tongue-in-cheek. After all, in writing about working as a taxi dancer, Wilder was doing double duty as a journalist. Wilder was not above being untruthful (in “Little Economics Lesson,” written when he was twenty-one, he claims to have received a “children’s chocolate vending machine” “thirty-five years ago”) or indiscreet (“Getting Books to Readers,” about the Berlin book trade, opens with: “A close acquaintance recently shot himself to death”) for the sake of a story. If a story can’t be reported, it can at least be manufactured: Edward III may not be available to be interviewed, but since all Wilder is interested in is the celebrity monarch’s fashion sense, he picks a local Englishman off the street and interviews “My ‘Prince of Wales’” instead. In his capacity as a reporter, he accepted money for “Here We Are at Film Studio 1929” and “How We Shot Our Studio Film,” which were really puff pieces for People on Sunday, the silent film that was based on a screenplay by none other than . . . Billie Wilder.

Phrases like “fact checking” and “full disclosure” were not in his vocabulary, and if you had pointed out that, aside from the movie reviews and feuilleton pieces, nearly every one of his articles involved some violation of journalistic ethics, he probably would have laughed in your face. The lesson of “Little Economics Lesson” is “each his own middleman.” The chocolate vending machine is “business personified” and when you put money into Billie Wilder you got words that were sweet, not wholesome. The best piece in the collection, “The Art of Little Ruses,” is a modest proposal for making lying “a mandatory school subject” on the reasonable grounds that school should teach children practical skills for success in life. At the end of the course, students will be prepared to master the most “difficult but vital” form of lying there is, namely, self-promotion.

Readers who come to Billy Wilder on Assignment to find the seeds of the films for which he is famous—nearly all of them, one assumes—will not be disappointed. But more than any particular correspondence between a reported event and a filmed plot point, it is the “voice” Wilder adopted as a reporter in Vienna and Berlin that found a home in the mouths of the unsentimental, fast-talking, image-obsessed characters that populate Double Indemnity (1944), Sunset Boulevard (1950), The Apartment (1960), and Some Like It Hot (1959). In the end, Wilder made it to America not as a foreign correspondent, as he once hoped, but as a refugee from the Nazis, traveling via Paris to Hollywood, where he established himself in the film industry in part thanks to the connections he had made through his reporting. Many of his family members perished in the Holocaust; by taking up journalism rather than law, the life he saved may very well have been his own. In Hollywood, the world capital of self-promotion, he completed the transformation begun by his mother years earlier and Americanized the name that had served as his byline. He was now Billy Wilder.

Ryan Ruby is the author of The Zero and the One: A Novel (Twelve Books, 2017) and Context Collapse (Statorec, 2020), a Finalist for the 2020 National Poetry Series Competition. Recent writing has appeared in Sidecar, 3:AM Magazine, VQR, and POETRY. He lives in Berlin.