Describing Joshua Cohen’s wonderful and elliptical novel A Heaven of Others is a bit like attempting to rehash an acid trip—no analysis can quite do justice to the feel of the experience. The premise: Jonathan Schwarzstein, a young Israeli boy, is blown up by a suicide bomber, and accidentally martyred into Muslim heaven. The setting: Paradise, the one that rings with the warm cries of infinite deflowerings and runs red with rivers of virgin blood. The prose: an incantatory dream speak—rhapsodic, uber-allusive—that gives the illusion of syntactical chaos, even as it’s stealthily held aloft by an elaborate structural architecture. The plot: Jonathan ignores his ill-begotten rewards (he’s only ten, after all, and the virgins—“Ostrich eggs burst fat filled fat with white grapes”—aren’t particularly appealing) in favor of a pilgrimage to the Valley Between Two Mountains, where it’s rumored that a man named Mohammed may be able to fix the clerical error, and whisk Jonathan across state lines to the correct afterlife.

The novel, first released in 2008 and recently reprinted by Starcherone Books, begins like a literary cover of the Talking Heads’ “Once in a Lifetime”—“How did I get here, if I am still an I? If how and where is here? Can still be asked and why?” The speaker is either God, an angel, Jonathan Schwarzstein, or Joshua Cohen, or so it can be surmised from the book’s full title, A Heaven of Others Being the True Account of a Jewish Boy Jonathan Scwarzstein of Tchernichovsky Street Jerusalem and his Post-Mortem Adventures in & Reflections on the Muslim Heaven as Said to Me and Said Through Me by an Angel of the One True God Revealed to Me at Night as if in a Dream. No matter, the story is Jonathan’s, and we soon learn the logistics of his accidental ascent into the wrong afterlife.

On Jonathan’s tenth birthday his parents take their son to a shoe store. Jonathan is standing outside the store when a boy with “maybe the earliest dew of a moustache” approaches and engages Jonathan in what at first seemed to be a deep embrace. Sweetly naïve, Jonathan feels the tickle of the boy’s moustache, and laughs as they hug tightly and almost seem to kiss. Then they explode.

It’s a powerful opening, enlivened by the grotesque physicality of Cohen’s descriptions. The street is an “asphalt birthday cake rising the candle of me,” and the bomber has “skin the milk of pigeons.”

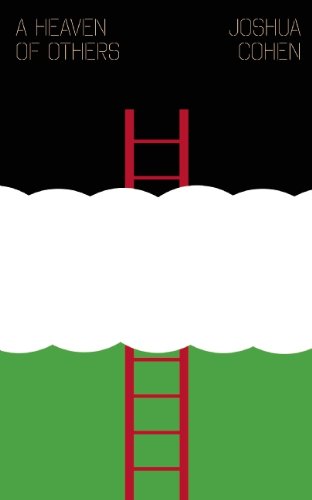

Next thing he knows, Jonathan is rising above Jerusalem among a mass exodus of pigs, “a huge pink hurling, oink-mad shuttling.” Jonathan climbs a ladder to heaven as if “walking a necklace of jingjangling bracelets.” Upon arrival he is greeted by “First Responders, archangelic professionals uniformed all in white, with their protective masks and their sanitary gloves…their flightless wings mere flutters of tape…” These equally lovely and terrifying images assault the reader, creating a mimesis of Jonathan’s experience; like Jonathan we’re thrown into a scary and unfamiliar world without even the comforting confines of grammar to hold on to.

Thus begins Jonathan’s journey. Along the way Jonathan encounters interesting strangers, wonders whether people pray in heaven (and if so why?), undergoes various metamorphoses, and remembers his short time on earth via Henry Roth-ish flashbacks. Through these child’s-eye observational moments we learn the specifics of Jonathan’s childhood: his piano-tuner father who walked, “himself like a tuned string… loosening, slackening throughout the day”; his mother’s battle with breast cancer, “A big black bumpishness that just grew larger or rather filled you largely despite what the doctors would empty…” These flashback serve to ground this inescapably ethereal novel and tint Jonathan’s journey with an even deeper pathos. In the process, he becomes much more than Cohen’s creation, much more than a prop for epistemological poetry (“existence before Creation was naked…Creation was a covering of this nakedness”). He becomes, for the reader, an actual child, flesh and blood, brutally sacrificed for political ends he will never have the chance to understand.

Granted, this is a difficult book, and not for the faint of heart. Potential readers might do well to come armed with an encyclopedia (or at least Wikipedia), a few dictionaries, a copy of the Qu’ran, and a breadth of both literary and religious knowledge (Paul Celan, S.Y. Agnon, Nelly Sachs, Saul Tchernichovsky, and Marco Polo are just a few of authors who Cohen has woven into the text). But comprehension seems antithetical to a book that so stringently makes the case for the incomprehensible nature of existence. Cohen’s after transcendence, not illumination, and in this he succeeds. In this book, all roads, even the horrifying ones, lead to Paradise.

Adam Wilson’s debut novel, Flat Screen, will be published by HarperPerennial in 2012.