To say that Minae Mizumura’s A True Novel is a remake of Wuthering Heights set in postwar Japan is not inaccurate, but this only begins to crack open the book. Like the Emily Brontë classic, Mizumura’s novel follows an impoverished boy who is haunted by his impossible love for a wealthy but wild girl, and who tries to heal himself by amassing a suspect fortune. But while Brontë wrote at a time when the novel was still a relatively new art form—young enough to be shimmering invention—Mizumura is writing in the dying light. This book, oddly compelling in its confluence of intellect and emotion, is her attempt to deal with the loose ends.

Born in Tokyo, Mizumura grew up in Great Neck, New York, and studied French at Yale. Her essay “Renunciation,” on Paul de Man, published soon after the literary critic’s death, is considered one of the first comprehensive treatments of de Man’s writing. It was adapted from an oral examination presented in place of one she had originally prepared for professor de Man before his death. In “Renunciation,” Mizumura, looking at the frequency and sudden disappearance of the word renunciation in de Man, concludes that he had, at the halfway point in his life’s work, renounced the possibility of renunciation.

In Mizumura’s subsequent, ambitious career, the idea of renunciation would take on new forms through her interest in rejecting, advancing, or otherwise artificially determining the course of language and culture. In Light and Darkness Continued (1990), Mizumura’s first novel, she had her fearless way with modern master Natsume Soseki’s Light and Darkness, an unfinished classic whose intentions have long been the subject of debate in Japan. (Soseki, for his part, had gone to London in 1900 to study English literature and became an ardent admirer of Jane Austen.) Mizumura’s second novel, An I-Novel From Left to Right (1995), was, by her accounting, the earliest instance of Japanese literature, with English intrusions, being printed as a horizontal text. A nonfiction book, The Fall of the Japanese Language in the Age of English (2008), argued that written Japanese should be preserved against the onslaught of English, an act she has been devoted to. From these bare facts, Mizumura begins to take shape as a writer for whom renunciation is immensely meaningful, giving almost physical dimension to writing through one’s choices on the page. (In “Renunciation,” she wrote, “If a death of a writer makes a difference in the way we read him, one manifestation of such a difference may be the sudden urge we feel toward grasping what we read as having its own history.”)

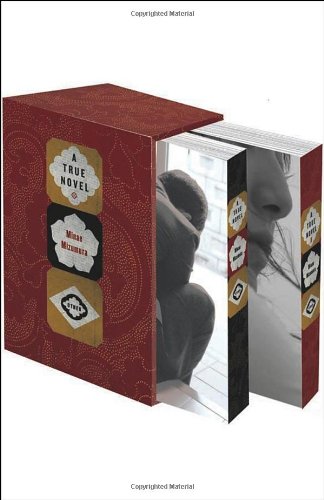

In A True Novel (2002), Mizumura’s first book to be translated into English (by Juliet Winters Carpenter and Ann Sherif), schoolgirl Minae, blasé and blurry in ’60s Long Island, finds her way into the life of tragic, rags-to-riches Japanese immigrant Taro Azuma through overheard, mesmerizingly foreign terms like breakfast nook, private chauffeur, and freighter. Minae grows up to become a writer, and she is handed, once again, the story of Taro on a dark and stormy night. An inkling of the plot, “a story just like a novel,” can be pieced together through further trails of words like rickshaw man, traitor, Sunday dinner, and rhubarb, which Mizumura often sets off in quotes or italics to denote the change in the air when a strange concept, a new direction, surface. Her sensory, outsider’s fanaticism with the experience of language makes A True Novel a book-as-book that self-consciously calls up the sum of books read. Certain readers, nostalgic for Brontë’s source material, will abruptly remember the patterns of the room in which they first saw the words moor and Heathcliff, the claimless boy whose single, overpowering name dooms him to be more of an idea than a man. Mizumura invokes Wuthering Heights, but a half-dozen other novels could reasonably be brought up instead: Great Expectations, Jane Eyre, The Great Gatsby.

What kind of story is this, anyway? Mizumura’s Minae comes of age on Anna Karenina as reworked into Arishima’s A Certain Woman. Three sisters debate whether their life is more like Chekhov’s The Three Sisters (itself a loose take on the Brontë girls) or The Cherry Orchard. Mizumura’s slow, dreamlike book world asks ancient questions (is it “impossible for a really good person to get rich”?) and counters Brontë with some progressive, briefly blissful, answers.

But there’s another novel in A True Novel: one about the history of the modern novel in Japan. Its Japanese title, Honkaku Shosetsu, derives from the “true novel” that came to be seen as the ideal type in Japan after 1868, when the country was opened to the West—the complete fictional worlds of Flaubert, Tolstoy, Dickens, Brontë. Against the honkaku shosetsu was the shi-shosetsu, or autobiographical “I-novel,” perhaps a more purely Japanese form in a land where the diary had been a respected genre for a thousand years. By the 1920s, critics were claiming that no successful honkaku shosetsu had been written in Japanese, opening a new round of challenge. Mizumura gives various linguistic theories to explain the form’s problematic practice in Japan while stating that the controversy is no longer relevant—by acquiring a “history,” the novel has been broken.

Yet Mizumura’s lack of ease with the true novel is, for her, troubling enough to become its own narrative. (This is compounded by the fact that her true novel is based on actual lives and events that happened to match the Brontë bones, unlike the strictly fictional space of the somewhat confusingly named honkasu shosetsu.) Was the author trying to do too much with too little, or was she taking the I-novel way out—and doing too little with too much? It probably doesn’t matter. Brontë’s teeth-grinding, outrageous characters have not much to do with Mizumura’s—who are, of course, unhappy in their own way. But the passive-aggressive, generative heart of storytelling hasn’t changed since Brontë’s Mr Lockwood entered his own obsession with the thought: “I felt interested in a man who seemed more exaggeratedly reserved than myself.”

Phyllis Fong is a writer based in Austin, Texas.