When the 13-year-old protagonist of Alberto Moravia’s Agostino learns about sex for the first time, the aha-moment does not last long. He listens to a peer matter-of-factly explain the anatomical workings of intercourse, and what used to be a hunch, tucked away in a corner of Agostino’s awareness, bursts into view and demands to be reckoned with. The new knowledge is like “a bright shiny object whose splendor makes it hard to look at directly and whose shape can thus barely be detected”—a simile of typical Moravian ingenuity. Light, that well-worn symbol of enlightenment, might reveal what’s hidden, but it can also be blinding. Knowledge has thrown Agostino into deeper darkness.

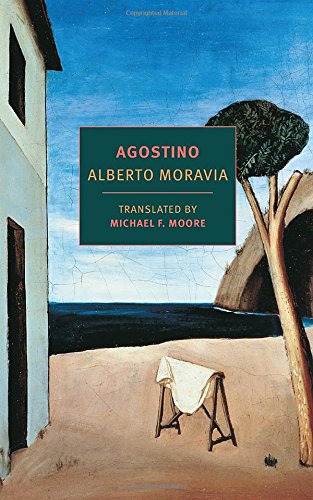

The reader revisiting or making a first-time trip through Moravia’s works will find a useful primer in Agostino, which was published in 1944 (after being banned by Fascist censors) and is now available in a new translation from the original Italian by Michael F. Moore. The novel’s slimness concentrates rather than curbs the power of Moravia’s chill and controlled prose, his stark and confident imagination, his unblinking existential preoccupations. All muscle, no fat. Adolescence becomes the stage on which two Moravian themes—a frustrated desire for knowledge, and the persistent mystery of sex—perform a synergistic dance.

Agostino, coddled and virginal, adores his widowed mother and her “beloved body” with the shamelessness of a child who has yet to recognize people as sexual beings. But his reverence is shaken when a young boatman joins the pair on their rides out to sea. The physical world, once so dependable, now bristles with an unfamiliar energy. His mother emits an “animal warmth” that disgusts him, and when her wet belly briefly brushes against his cheek, he feels it “beating strangely, as if it had a life that didn’t belong to her or had slipped past her control.” In the adults’ “insinuating, insistent, spiteful” conversations, a reproachful comment seems to be “a cover for an affection he could not grasp.” The air is electric with flirtation that Agostino can’t fully decode.

So begins the corruption of the boy’s pure filial love with sensuality. Determined to lose his innocence entirely, Agostino embarks on a self-mortifying spectatorship: He looks for signs of kisses or caresses on his mother’s body; he furtively watches the partly undressed woman unclasp her jewelry before the bedroom mirror. It’s a cruel education. Instead of achieving the “virile, serene condition” that he hopes for, he learns the extent of his ignorance.

Defined one way, adolescence—with its mood swings and blindsiding first loves—is a period of hyper-feeling without catharsis. Many of Moravia’s protagonists, young and old, share this adolescent quality, trying relentlessly to understand what they cannot. It is a quiet wonder to watch Moravia create this discordance on the page. He positions the blade of his characters’ psychological investigations—incisive, ruthless, dogged—against cosmic unknowing—obscure, shiftless, bloated. How does he do it? At first glance, the writing seems transparent in its intentions, almost crudely so. Protagonists rarely leave the implications or meaning of an event unexamined, going so far as to extract themes that a reader could reasonably intuit on her own. Agostino, for example, not only likens his mother’s negligee to the gown worn by a woman he glimpses through the window of a local whorehouse, but also explains why this observation—so loaded, it seems in need of no further explanation—should bother him.

But there’s something beneath the physical and psychological specifics that Moravia so attentively describes. When a strange man named Saro tries to seduce him, the boy observes a host of unnerving details: Saro’s grabby behavior, his “inflamed flared nostrils,” “the hairs, gray and dirty, rustling on his chest.” Agostino can’t put his finger on what’s going on, can’t excavate the meaning from the facts. That his eyes are wide open makes the experience all the more frustrating. Total ignorance would have been preferable.

Moravia recreates for the reader this frustration of unknowing-in-the-midst-of-knowing through a strategy that might be called selective muting. During the outings to sea, we hear almost no words directly from the boatman’s mouth, and his conversations with Agostino’s mother are described, not transcribed. The boy is listening to every word, but he understands—in the true sense of the term—little. The muting occurs most notably during his critical moments of discovery. Consider, again, the scene in which Agostino learns, from a more experienced boy named Sandro, what his mother and the boatman are doing behind closed doors:

Agostino noticed [Sandro’s] strong tanned legs, which seemed enveloped in a cloud of gold dust. More blond hairs escaped from his groin, poking through the holes in his red swimming trunks. “It’s very simple,” he said in a strong clear voice. And speaking slowly and illustrating his points with gestures that were effective but not what might be considered vulgar, he explained to Agostino something he seemed to have always known and, as if in a deep sleep, forgotten. His explanation was followed by other less sober descriptions.

The description of Sandro and his pubic hair feels more sexual than any of the lines that follow, in which, we’re to assume, graphic explanations are underway. Afterward, Agostino decides with an “almost desperate resolution” that he must sleep with a woman, to be released from the anxieties of his incomplete knowledge. But two bodies do not make an answer. He doesn’t know it yet, but what moves the boy to such tortured extents is not the sexual act itself, but the mystery for which even the sophisticate has no name. Moravia may not know its name either, but he does know how to summon it.

Esther Yi is a writer in Berlin.