WHEN THE WRITER MAYUMI INABA meets Mii, the kitten who will become “the center of her life,” the animal is stuck in a school fence, screaming for rescue in the night air: a “little white dot” deposited there “out of malice or mischief” by a culprit long departed. There is no sign of her mother or littermates, no evidence that she is owned or loved or named. She is flea-bitten, only a few days old, exhausted, and of obscure origin. “All I knew,” Inaba writes of the moment she collected this defenseless being into her hands, “was that she must have felt utterly desperate.” Any cat person worth their fur-covered clothes can guess what happens next; Inaba is subsumed in devotion to this creature, with its face “the size of a coin.” Her life will be ruled by Mii until Mii’s own life ends, and that is right and good.

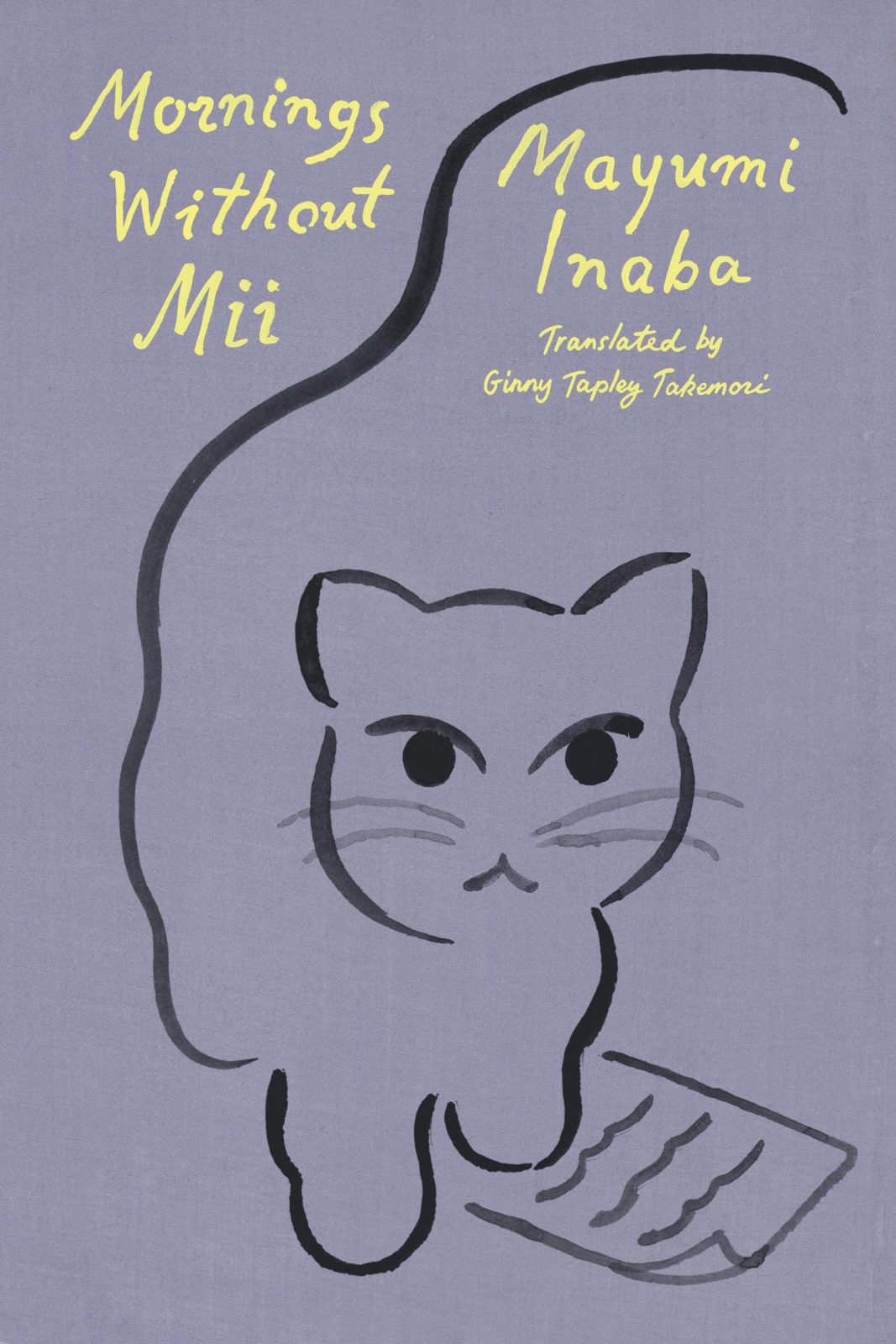

Cat people are the only conceivable audience for Mornings Without Mii, an uneventful memoir in which a Japanese woman—married at the beginning of the book, later divorced—loves and lives with a cat who succumbs to old age. Who else would be entertained by meticulous descriptions of Mii sleeping, playing in newspapers, sniffing everything she comes across, lapping up milk? Much of the book is devoted to Mii’s habits and tastes, her comings and goings, the style in which she arranges her body, and Inaba’s passion for documenting every detail. “Whenever I saw a new expression on her face, I wanted to keep gazing at it until I tired of it,” Inaba writes, well aware that this boredom will never come. “I could gaze at her forever,” she says. “I never tired of watching her.” That the fascination is not always reciprocated is no impediment. In an early poem for Mii, Inaba writes, “I call to you but you don’t come. / You don’t come, so I go to you.”

Nothing here will surprise a cat lover, not the engrossed study and indefatigable solicitousness or the stressful relocations and the health scares. The terminus of this relationship is a forgone conclusion—with or without the giveaway of the book’s title. Mornings with Mii will inexorably give way to mornings without, which means the people most likely to appreciate the book will also find it excruciating. “I could barely get through it,” says Sloane Crosley in a blurb. A friend of mine teared up upon simply hearing the title. Humans die, too, of course, we all know that. And the loss is terrible. But I would not have psychically braced myself to pick up a book called Mornings Without My Sister/Husband/Friend. Nor would I have felt so raw throughout. Love is always the Trojan horse of grief, but companion animals make this unusually clear, probably because their lifespans are so short.

Though Mornings Without Mii opens with an illustration of how vulnerable cats are to the whims of human beings—orphaned baby Mii is confused and frightened, fighting against almost certain death, “puffing her body up as much as she could to keep from falling”—the book is primarily a testament to how vulnerable we are to theirs. Inaba’s allegiance to Mii is immediate and uncompromising. “The moment I got home, the first thing I did was search for Mii,” she writes of her new routine. “Her development as the seasons passed became the main topic of conversation between me and my husband.” When the author and her husband must move and cat-friendly accommodations prove impossible to find, they keep Mii a secret from their new landlords. When Inaba and her husband separate, and she must again secure housing, she panic-buys instead of rents, to ensure that Mii will never lose a home again. “Our intimacy was spun without words and in time formed into an unbreakable bond,” she writes. “We slept in the same bed . . . and in the morning the first thing we saw was each other.”

Inaba’s prose, as translated by Ginny Tapley Takemori, is deliberate and plain, a strong conduit for the emotional potency of her connection with Mii. She resists sentimentality even in moments of sorrow. “I had already lost all sense of reason,” she writes of repeatedly searching the same corners of her modest apartment, sobbing, when Mii goes missing. After Mii is returned by the upstairs neighbor who briefly took her in, Mii pees on Inaba profusely, a moment Inaba regards as proof of how “we mutually supported each other”: Mii was afraid to go in the stranger’s home. Inaba’s precision is particularly effective when Mii starts losing the ability to evacuate on her own. “I had never been so happy with the work of my own hands,” she writes of her discovery that she can manually express Mii’s poop as well as her urine. “I wanted to spend every day using my hands to help her.”

But Inaba’s writing, as accomplished as it may be, is affecting to me because it draws on a broad and exquisite sensitivity that Amy Hempel, in her short story “At the Gates of the Animal Kingdom,” aptly named “the tender vittles emotion.” It is a protective, even worshipful fellow feeling for the animals of the world, especially the domesticated and dependent ones, regardless of whether they are unknown to us or personally beloved, and it’s an impulse easily belittled by those who’ve either never felt it or refused to tolerate it in themselves. (The main character in Hempel’s short story, babysitter Mrs. Carlin, is careful to protect it in her younger ward when the boy’s older brother threatens to shame it out of him.)

When allowed to flourish, the tender vittles emotion engenders a cherishing usually directed at babies or sleeping loved ones, and it diffuses itself into the world like a mist. I’ve cried over strangers’ social-media tributes to their departed cats after reading several words, and I’ve felt anticipatory pangs of loss for acquaintances and friends who are simply sharing photos of their cat looking cute. Mrs. Carlin cries during a cat food commercial, then, a little later, addresses her dog and cat in her mind: “You have made my happiness for thirteen years.” Inaba evinces a similar degree of attachment when she refers to the dying Mii as “her partner” and writes, “I felt an intimacy we had never had when she was young running from her body to mine, and from my body to hers, supporting each other.” There is an intensity here that, being widespread but not universal, borders on the deranged, yet it is one of the most precious, vital sensations I know. To adore without reservation—which is, essentially, a religious experience—is to feel that one’s own life has meaning and purpose.

Inaba’s writing is strongest when Mii is furthest into her decline. Inaba stops listening to music so Mii can enjoy the quiet, keeps windows cracked in a futile attempt to clear the urine-dank air. When friends reach out, she tells them, “My cat is dying. I’ll call you later.” She incessantly anticipates the moment, and mulls over what sort of death is most “suitable” for Mii: “Was it better to hold her as she died? Or was it better for her to die quietly while her human wasn’t there?” There’s so much we can’t know about the animals we love, and the responsibility we assume within that void of ignorance haunts us during and after their passing. When they take up residence in a small fifth-floor apartment and leave behind the home where Mii could freely venture outside, Inaba wonders if she has committed a moral crime: “Maybe I should have left her in the familiar woods of Kokubunji, even if she did end up dying there.”

Yet our pets give us such relational certainty, so much existential reassurance, that the sacrifices of clean air and no music are hardly felt as such. “There wasn’t a single thing that I’d ever felt had been lost between Mii and myself,” Inaba writes near the end. “I realized that my time with Mii hadn’t been disturbed for a moment.”

Mii dies at home, late at night, with Inaba watching. She sits by her cat’s side until it is morning, crying more than when she split up with her husband, more than when she lost her father. Outside, she gathers weeds she will use to decorate Mii’s body. (“I didn’t know much about weed types,” Inaba thinks when she walks her neighborhood streets, “but I knew which ones she liked and didn’t like.”) A neighbor comes to the door with homemade sherbet; Inaba tells her the news and the neighbor encourages Inaba to eat a little before she leaves. “She was definitely happy with you,” the neighbor says. “And you were happy too, weren’t you, Inaba-san?”

I know many people who’ve lost a pet and said, “I can’t do it again.” But saving yourself from the end means giving up the beginning, a prospect I find far more crushing. What would have become of Mii if the breeze had not carried her cry to Inaba’s ears? And what would have become of Inaba if she had not answered? Alone, Inaba crumples down beside her best friend’s green-wreathed body and eats the cold, sweet sherbet. “Yes,” she thinks, “I was happy.”

Charlotte Shane is cofounder of TigerBee Press. Her latest book is An Honest Woman: A Memoir of Love and Sex Work (Simon & Schuster, 2024), which she discussed with writer Jamie Hood in Bookforum’s Fall 2024 issue.