There is a type of casual leftist who embraces a condescending, evangelical style that I once thought belonged solely to the right wing, and that always bothered me just as much as Republican policy agenda itself. The liberal version of this style is exemplified by the rabblerousing progressive website Upworthy, which is always preaching, outraged, to the choir: “Watch this writer ask one question about equality that will blow your mind,” “Share if you believe in justice,” “Think teachers are overpaid? Read this chart.” Its readers constitute an audience that moves from one outrage to another—the rude treatment of Sandra Fluke, something mean Anne Coulter said, fracking—combining an irritating passion for social justice with an abiding shallowness.

Chris Kluwe, a punter for the Oakland Raiders, seems tailor-made for these click-and-share liberals. Kluwe first gained notoriety outside football for an enraged Deadspin post he wrote in defense of Brendon Ayanbandejo, a former Atlanta Falcons linebacker who caught heat from a numskull state rep for speaking on behalf of marriage equality. Kluwe’s much-circulated screed included the lines, “I can assure you that gay people getting married will have zero effect on your life. They won’t come into your house and steal your children. They won’t magically turn you into a lustful cockmonster. They won’t even overthrow the government in an orgy of hedonistic debauchery.”

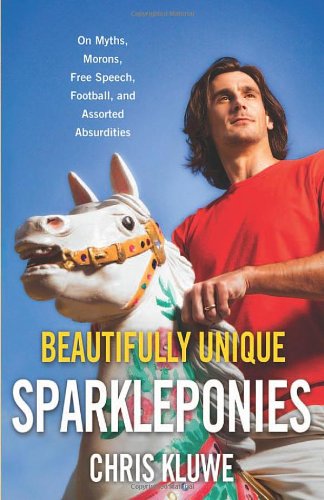

The rant was a welcome burst of angry protest, but it was also a prime example of the kind of ham-fisted polemic I’m talking about, characterized by moral superiority, shrillness, and deadly unfunny jokes. Should you want more of the same, there is now Beautifully Unique Sparkleponies: On Myths, Morons, Free Speech, Football, and Assorted Absurdities, which gives us pages and pages of Kluwe brashly holding forth on a variety of contemporary issues.

Kluwe handles politics about as gracefully as your typical book critic handles a football (George Plimpton not included), and Sparkleponies lurches from topic to topic with “let’s do this” lack of forethought. The book is a grab-bag of short essays about oh, this and that, written in the tone of an overconfident dude who’s had a little too much to drink at a backyard barbecue and wants to show you just how down he is. “Just Deserts” lectures the reader about how as the social safety net disintegrates, “you get the government you deserve.” “Aliens” is a dime-store Vonnegut vamp in which a mad foreign planet turns out to be Earth itself (!). And in the noxious “Love, Dad,” Kluwe rips into a bag of moldy fatherly chestnuts: “Let’s see, what else?” he writes, chummily. “Oh, an important one: never forget the Golden Rule.” At least it’s efficient: In a mere 251 pages, Sparkleponies manages to cover topics including but not limited to gay marriage, extraterrestrial life, the wrongness of both stubborn atheists and Bible-thumping Christians.

The kicker, if you’ll excuse the pun, is that despite being annoyed by Kluwe, I found myself agreeing with him in general terms. Homophobes, sexists, holy rollers, and libertarians drive me every bit as crazy as they drive Kluwe. But as is the case with many steamroller e-pundits, Kluwe leaves no room for discussion, never considers other viewpoint, and seems entirely allergic to nuance. For instance, Kluwe insists that gay people are no different from straight people. But that’s not really true: there is a distinct gay culture, arguably a “gay” way of acting, and other differences to embrace and celebrate. I would love to read his imagining of how gayness might play out in the NFL. But that would probably require more than a five-paragraph essay.

If you were wondering how Kluwe came by his beliefs, he is vexingly tight-lipped when it comes to his upbringing. An essay called “Introspection” opens, “This is the part where I tell you about me.” But then he doesn’t tell us anything. He begins each paragraph with the phrase “Growing up,” as in “Growing up, I was always the nerdy kid with thick glasses”; “Growing up, I was the best player on my soccer and baseball teams”; and “Growing up, I always had my head in a book.” The complicated feelings that these conflicting interests and identities might have given birth to are never explored. Did being different get Kluwe teased, or imbue him with an empathy that informed his politics? Not likely. The Chris Kluwe of Sparkleponies is sui generis: He seems to have emerged from the womb believing in truth, justice, the American Way, and his own rectitude. He finds his emotional and intellectual development—which could have made Sparkleponies passingly interesting—worthy enough to note but unworthy of exploration.

“I lack clarity,” Kluwe writes in another half-hearted essay about his early years. “Everything’s seen as an amorphous blob.” Not to put too fine a point on it, but if that’s the case, maybe writing a book’s not such a great idea.

Kluwe presents himself as an odd bird, and it’s true that the NFL has not produced many vocal progressives over the years. But there is a long tradition of athlete-advocates in America, and Kluwe’s cleats are digging into the shoulders of people like Jackie Robinson, Mohammed Ali, Billie Jean King, Roberto Clemente, and Arthur Ashe, rightly revered sportsmen and women whose careers (and in some cases lives) were threatened when they held to the courage of their convictions. They made their names not by writing, but by acting—by playing ball, resisting the draft, and accomplishing relief missions.

I imagine that Kluwe’s involvement with Athlete Ally, an organization that promotes GLBT acceptance in sports, will create more of a social impact than a quickly scribbled profit opportunity like Sparkleponies. His mere presence at a gay pride parade or on the Ellen Show is more powerful than his writing. Perhaps it’s just Sparkleponies’s cover, which has Kluwe riding a carousel unicorn in a mock-heroic pose, but while reading the book I kept imagining one of those liberal-luring headlines: “Think Football Players Only Care About Football? Read This!” If Kluwe really wants to proceed as an activist, he would do well to put down the laptop and follow the example of his athletic forbearers, rather than chase after the next source of link-bait outrage.

Sam Biederman lives in Brooklyn. His writing has appeared in publications including n+1, Salon, and the Nation.