When I first heard of this book, earlier this year, I felt a mix of fascination and dread. Listing every appearance of punk rockers on film seemed laughably masochistic, for both reader and writer. That a friend was one of the editors (Zack Carlson and I have intersected in the punk underground world for a dozen years) made the venture a potential lose-lose for me, leaving either disappointment or jealousy. And how could two editors actually pull off such a grandiose project? And even if they did, how could they convince the reading public that their labor-intensive thesis—presenting an entire universe through the lens of punks on film—had literary merit?

Thankfully, the editors, Carlson and filmmaker Bryan Connolly, chose 1999 as their endpoint. The book’s range begins with 1976’s The Blank Generation, a shoestring budget documentary shot at CBGBs featuring the Ramones, Patti Smith, Television, and other proto-punk bands, which Carlson calls “the Zapruder Film of early punk rock” (the first narrative punk film—a porno named Punk Rock—didn’t appear until the following year), and takes stock of every film up to 1999’s Frezno Smooth (a film Carlson calls “the worst,” deadpanning, “it is my unpleasant duty to inform you that this movie exists.”) This cutoff point makes the project feasible—massive, but finite. The end-product is less of a primer than an encyclopedia, with lavishly illustrated capsule reviews bracketed with a dizzying array of interviews with punks and filmmakers.

Within those chronological goalposts are fuzzier boundaries of style. For inclusion, a film’s character “must be visibly identifiable [as a punk] and/or . . . must express a strong dedication to some variation of the punk lifestyle.” Clear parameters, yet Carlson and Connolly have taken some abuse for not including two films—Straight To Hell and Over The Edge—clearly outside their mandate. It’s hard to imagine this book without these restrictions. The boundaries of what constitutes “punk”—a hugely lucrative market for at least the last fifteen years—are porous. The book simply couldn’t have existed any other way.

Within this volume, two camps emerge. The first is the tiny fraction of films that depict punks as sympathetic and marginalized figures; the second includes the vast sweep of Hollywood films that depict punks as lawless subhuman marauders. The editors highlight this divide as the difference between the benignly portrayed waifs of Suburbia and the “Vidiots” of Joysticks, two films “made in the same year [1984] in the same city for the same age demographic.” Diplomatically, the editors dedicate the book to both Suburbia’s director Penelope Spheeris and Joysticks actor Jon Gries.

In one of Destroy All Movies‘ more than sixty interviews, Fugazi’s Ian Mackaye sums up this divide from the punk’s perspective: “I feel like that’s always the default [for Hollywood]. Punk is a joke.” For twentieth-century punks, misrepresentation begat real-life discrimination, but watching these movies now, that misrepresentation provides endless entertainment. Unsurprisingly, Hollywood got punk spectacularly wrong. The fruit of that wrongness is a fabulous assortment of punks as aliens, cyborgs, gang members, mutants, wasteland warriors, and zombies; comic ciphers onto which 1980s filmmakers could project that decade’s fears of crime and nuclear apocalypse (characterizations that mostly vanished in the 1990s—nineties film punks, newly mainstream and symbolically rudderless, are far less fun).

Even limited to twenty-five years, the number of films the book covers is daunting. Of the twenty-thousand movies Zack tells me were scanned, less than 6 percent yielded punks. That still gives the book more than one thousand films to describe (so far, the self-diagnosed “autistic obsessive” Carlson tells me he found only eleven titles he missed, all of which are foreign). Before reading Destroy All Movies, I’d fancied myself an expert on Escape From New York rip-offs, Italian and otherwise. I had no idea there were so many garish and anonymous punk apocalypse movies loose in the world.

Even within this sprawling assemblage of movies, it’s astonishing how many films have been completely lost to obscurity. There’s the real-life band Fear’s singer Lee Ving playing “the part he was born to play,” a self-parody in Get Crazy (1983), and a punk teen Emilio Estevez in 1983’s Nightmares (a full year before appearing in Repo Man). Then there are all the gloriously fictional bands (Iron Skulls, Ivy & The Shitty Rainbows, The Late Term Abortions, Rotting Filth), clubs (The Incinerator, Punk’s Place, Satan’s Pit), and caricature punks (Airhead, Crud, Piggy, Scratch, Scuz, Splatter, Suicide).

Nearly every page yields a great story. A food fight kept The Germs out of Cheech and Chong’s 1978 movie Up In Smoke. The Another State Of Mind (1984) premier was ruined when one of The Adolescents “assaulted the projector.” In 1981, Los Angeles Police chief Daryl Gates wrote Penelope Spheeris, requesting that she not show her documentary The Decline of Western Civilization in his city. Fugazi were asked to appear in a 1996 bowling comedy called Kingpin.

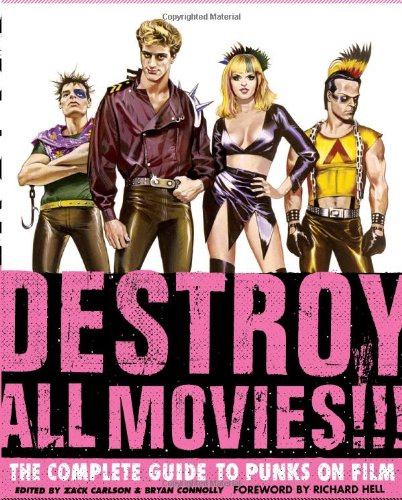

It’s hard to tell where Destroy All Movies stands in the pantheon of film books (although with three-dozen color plates, and thousands of gorgeous inserts of film stills, posters, and ephemera, it can hold its own against most Taschen cinema tomes). There’s a slight inconsistency in tone within the reviews—the book lists seventeen contributors—but that’s a petty complaint in a work of this size. The canon of good punk books, however, is much smaller. Within the sub-sub genre of DIY punk that Carlson and I inhabit, there has been an alarming trend toward slapdash punk memoirs; cheap impersonations of genuine oral history that betray the work ethic of the DIY punk scene. Destroy All Movies is a product of the tireless DIY work ethic: It is one of the most painstaking books ever written on punk rock. As such, it stands in the rarified league of Banned in DC, Fucked Up & Photocopied, and the long out-of-print masterpiece Loud 3D. Carlson and Connolly have managed to make a volume with both intellectual relevance and deep entertainment value. And if you don’t have time to actually read through all 1,000 entries, it’s still a blast just to look at.

Sam McPheeters is a freelance writer living in Pomona, California.