There are countless books on the history of British music in the ’50s, ’60s, and ’70s. Consider, for example, the eight hundred-odd books that Amazon currently has about the Beatles, or the numerous volumes chronicling the roots of mod, glam, punk, and post-punk. The veritable mountain of literature on David Bowie alone could take a lifetime to sift through.

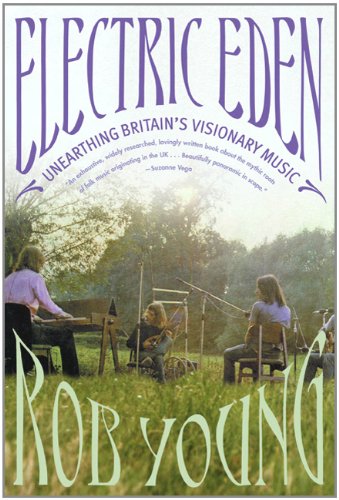

In Electric Eden, Rob Young uncovers a hidden seam of British music, a fascinating tangle of stories that have not been told in great detail. This encyclopedic tome, which weighs in at over 600 pages, grapples with the unwieldy history of British folk music—from better-known groups like Fairport Convention and the Incredible String Band to more obscure characters like Vashti Bunyan and Comus. It is a story that takes place not in the city but in the world outside of it. “The Malvern Hills, the mountains of Wales, the Yorkshire Dales, rural Scotland, villages in Essex, Kent, Sussex and Cornwall,” Young writes. “This is a music that has come from the hinterlands, whether indigenously or from city people who have relocated to the country in pursuit of the myth of the natural life.” It is not just the bucolic countryside that Young is referring to, but something altogether more conceptual—“the secret garden in British culture,” as Young terms it, “the gate that swings open to reveal a time-locked pastoral haven.” That journey is an inward exodus, he writes, as much as it is a physical one.

American folk and folk-rock of the period has been extensively documented; the amount of scholarship about Bob Dylan could fill a small library. Add to that pile the obsessively curated collections of early 20th-century folk music preserved and promoted by trailblazing figures like Alan Lomax and Harry Smith. The old, weird Britain, on the other hand, was less well documented than its American counterpart, and its history is less traceable. Young gives ample ink to collectors like Cecil Sharp and Francis Child, and Albert Lloyd, who was, Young writes, the closest analogue that Britain had to Lomax. Lomax, for his part, also had close connections with England—he spent eight years there, beginning in 1950, a period that Young examines extensively. But Young’s search for the roots of folk lead him into a more distant past. He digs back to the beginning of the 20th century, to the composer Gustav Holst, best known for his orchestral suite “The Planets,” who possessed a deep interest in Hindu mythology and spirituality. The early 20th-century composers Frederick Delius and Vaughan Williams figure into Young’s story too. This book is wide-ranging enough to contend with Rudyard Kipling, faeries, G.I. Gurdjieff, Paradise Lost, Marshall McLuhan, Arthur Machen, and a member of the Incredible String Band named Licorice.

If anyone gets short shrift in Young’s Eden, it is the big guns—the Pink Floyds and Led Zeppelins of the world, groups that flirted heavily with folk and folklore but rapidly transcended (or trampled) that secret garden with their massive success. These rock gods only make brief cameo appearances here. Near the beginning of the book, Young quotes an essay that Lomax originally wrote in 1950: “What was once an ancient tropical garden of immense color and variety is in danger of being replaced by a comfortable but sterile and sleep-inducing system of cultural superhighways.” Young, too, is interested in preserving color and variety in his book, and he is especially attracted to the marginal, peculiar aspects of England and its culture. “If I lived on the West Coast [of America] how on earth could I think about elves and fairies and goblins and old English castles and churches?” says Bob Johnson, former guitarist of the folk band Steeleye Span. “I used to spend months looking at brasses in old churches. I’m just steeped in England, as a hobby.”

Electric Eden, which came out in the UK last year to rapturous acclaim, is now getting its US debut, and one wonders if some of this book might get lost in translation. Even many of the more recognizable British names featured in the book, such as Pentangle and Donovan, were mere radar blips on the American consciousness. The most spellbinding parts of Electric Eden for many US readers are likely to be the chapters on Sandy Denny and Nick Drake—characters that cut closer to the heart of the American myth, with compelling, tragic, made-for-TV lives.

But among indie rock fans, interest in the outer margins of folk music is at an all-time high. For acolytes of musicians like Joanna Newsom, Panda Bear, and Devendra Banhart, Vashti Bunyan’s 1970 album Just Another Diamond Day is more relevant, and probably more revelatory, than the Woody Guthrie records of their parents’ generation. The book’s focus on the weird, the odd, the lesser-known—Vashti in her caravan was indie before it was indie—will find new resonances among a younger, Pitchfork-reading demographic. The yearning for exploration—both outward and inward—that Young details in his book is British in its emphasis, but the feelings are universal. “Folk music derives its power from its connection with universals—the cyclic revolve of the seasons and the ritual year—and from archetypes that can be discovered and reinterpreted again and again across many of the world’s legends,” he writes. This book taps into these universals, by chronicling a music that is, in his words, “concerned at a root, instinctive level with a form of imaginative time travel.”

Geeta Dayal is a music critic based in Boston. She is the author of Another Green World, a book on Brian Eno (Continuum, 2009). She blogs at theoriginalsoundtrack.com.