THIS IS A GOTHIC TALE. In the summer of 2002, a professional illustrator and single mom in Chicago went to her fortieth-birthday bash, a gypsy-themed affair that her young daughter told her not to attend. A premonition? At the party, a mosquito bit her. Perhaps she slapped it dead; maybe it stayed attached, vampirically feasting. The result was no mere itch, but a health spiral. She had contracted West Nile disease, in a city very far from either side of that river, plus meningitis and encephalitis, paralyzing her lower body. Her drawing hand no longer worked: her livelihood was at stake. She moved in with her mother, whose dining room could accommodate her hospital bed and wheelchair, and enrolled in the fiction writing program at the Art Institute of Chicago. There were stories she wanted to tell. Maybe she’d revisit an abandoned screenplay from the ’90s, about “a werewolf lesbian girl being enfolded in the protective arms of a Frankenstein trans kid.”

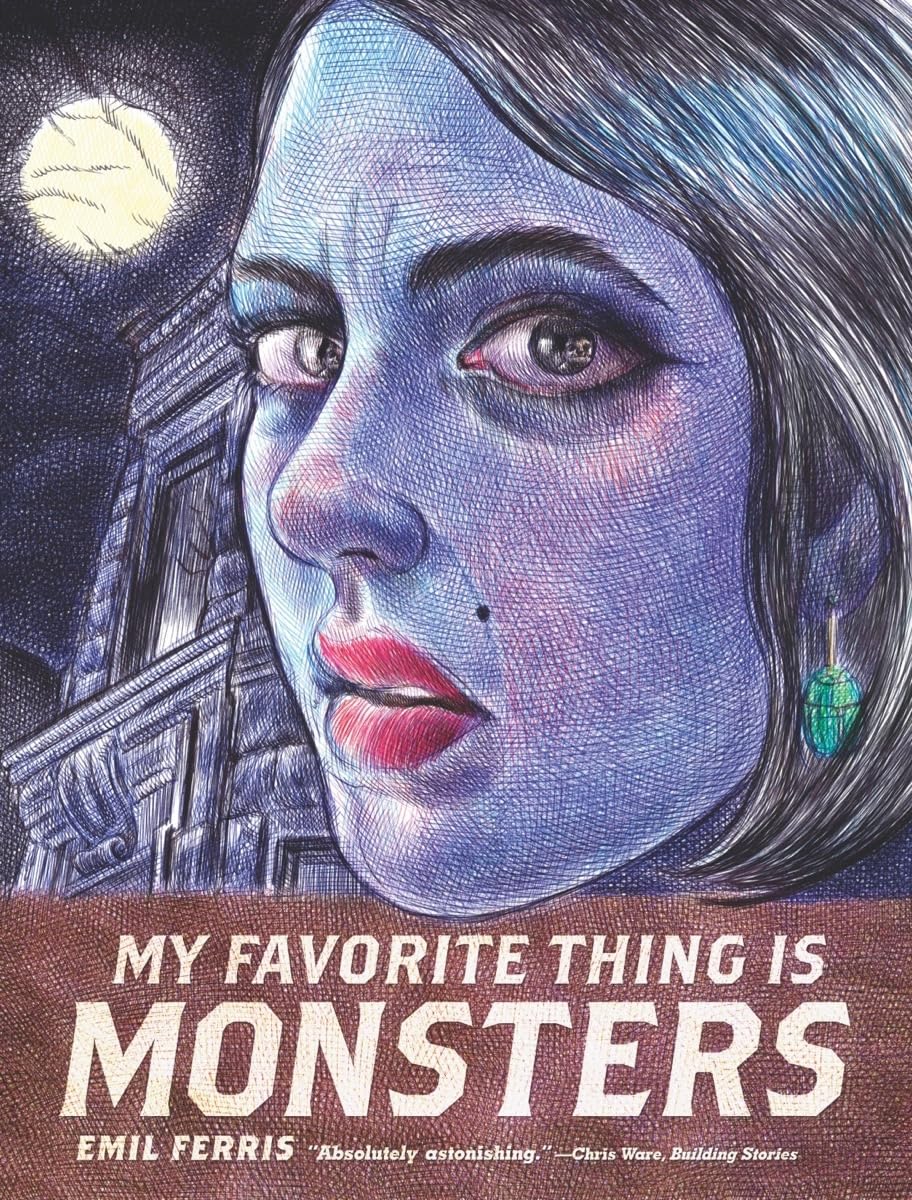

She also took a comics class, falling hard for Art Spiegelman’s Maus. (She used to love cartoons, and would copy strips from the paper with alarming facility; why had her interest waned?) At her daughter’s urging, she forced her muscles to relearn how to draw, duct-taping a quill pen to her afflicted hand. In time her powers came back. She started a graphic novel, turning her little lycanthrope into a freakishly charismatic narrator-illustrator: ten-year-old Karen Reyes, uptown Chicagoan and magical thinker. She has an absent dad (depicted as the Invisible Man, bandages around a head-shaped void), a dying mom (loving, Catholic, homophobic), and a brother named Deeze, for Diego Zapata. Their apartment building is stuffed with colorful characters: a one-eyed ventriloquist, a mobster and his oversexed wife, and a jazz drummer married to Anka (“the most beautiful woman I ever saw”), who survived the Holocaust in body but not spirit. Anka’s violent death early in the story sets Karen in gumshoe mode. Drawing herself as a wolf-girl in a trench coat, she considers possible suspects (including Deeze) and listens to a tape recording of Anka vividly relating (to whom?) a bleak childhood as the daughter of a prostitute in Berlin and the soul-killing way she escaped from a Nazi death camp. The chapters are punctuated by the lurid covers of the horror magazines that Karen reads—lovingly imagined counterfactuals with names like Ghastly and Tales of the Eldritch and the Arcane. These seem even more alive than the real-world speculative fiction of Planet of the Apes, seen on a theater marquee.

A misfit artist attracted to girls, Karen draws herself as fanged and hairy, à la Lon Chaney Jr. in the 1941 horror classic The Wolf Man. She has so internalized the myth of monsters that she dearly hopes one will bite her and/or her ailing mother, making them undead—keeping her mom alive. In real life, had the artist, too, transformed? (“I live like a mole in a hole,” she would later say.) The partying mosquito was her version of Peter Parker’s radioactive arachnid, except instead of turning her into Spider-Man, it bestowed the comix powers of Spiegelman and Alison Bechdel and Charles Burns all at once. For six years, fueled by free coffee from bank lobbies, she thought big and worked small, using the humblest materials—Bic ballpoints, college-ruled notebooks—to evoke the squalid, shadowy, sometimes glorious late-’60s Chicago of her youth. Her supple layouts blurred the lines between urban blight and childlike fantasy. The soft blue lines of the paper and even the three holes in the margin became as much a part of the book as her wizardly cross-hatching, grounding Karen’s flights of fantasy in schoolgirl reality.

But what was the book? On a calling card to entice potential publishers, she drew a three-eyed Lovecraftian beastie and wryly dubbed her epic “an unholy amalgamation . . . a type of monster in itself,” comprising “20% memoir, 10% humor, 5% urban grit, 38% mystery, 15% historical fiction, 5% romance.” It didn’t matter. Scores of editors turned the book down before Fantagraphics acquired it, for a Halloween 2016 release. In a diabolical twist, the final copies were en route from the Chinese printers when (per the artist’s GoFundMe) “IT WAS BOTH LOST AT SEA AND THEN ‘ARRESTED’ BY THE PANAMANIAN GOVERNMENT.” The shipping company had just gone bankrupt.

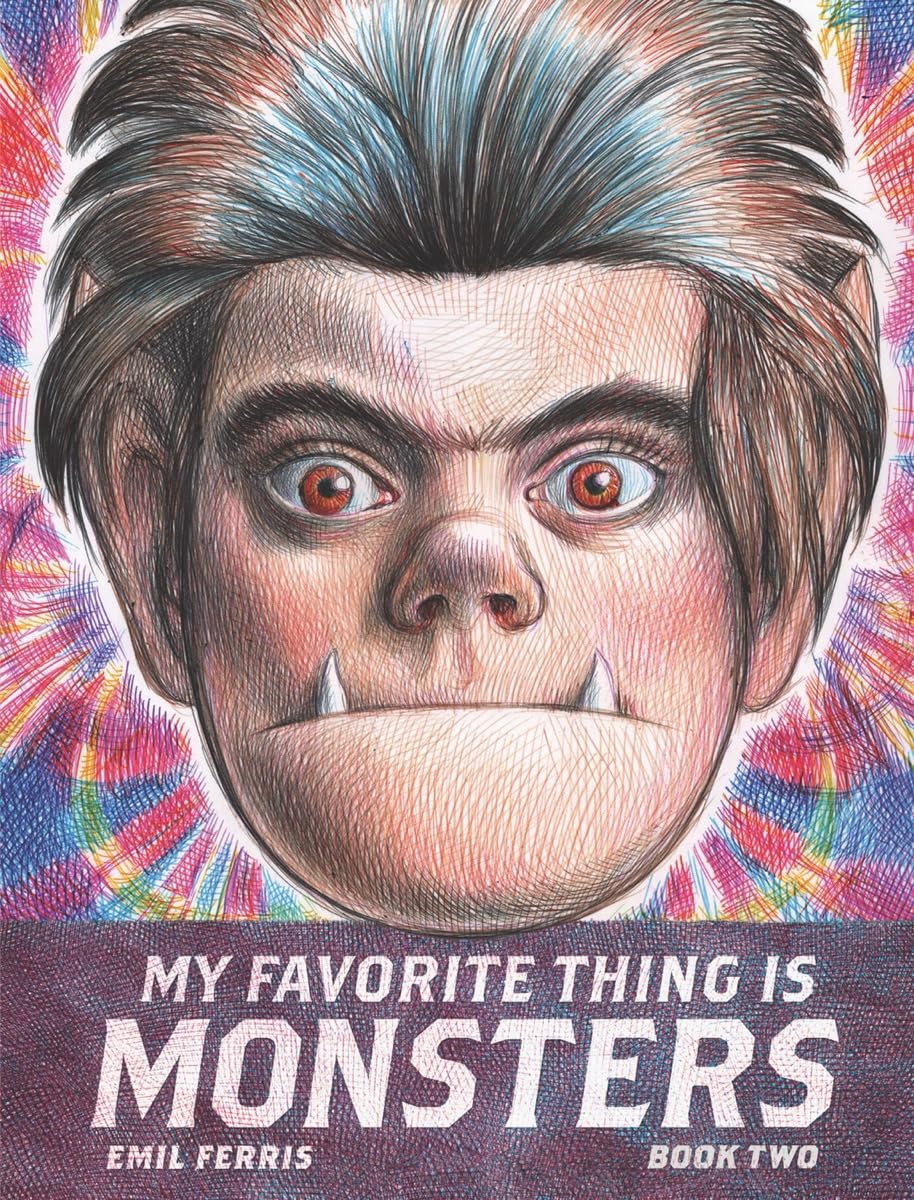

On Valentine’s Day 2017, the graphic novel titled My Favorite Thing Is Monsters finally appeared, to unanimous acclaim. The artist, Emil Ferris, was unknown in comics circles, but the sheer power of her debut made most contemporary cartooning look like cocktail-napkin doodles. Instead of another anemic, digitally futzed-with comic—the kind that seems composed directly on a tablet—Ferris renders tender and shocking images that seem to breach the third dimension. It’s an unruly graphic novel that wants to be everything everywhere all at once. For four-hundred-plus pages, Ferris braids murder mystery and Holocaust narrative, queer coming-of-age story and creature-feature fan-fic, Greek myth and drug trip, art history and underworld noir.

The only hitch was that the story didn’t end when the book did. Readers arrived at a cliffhanger in which Karen seems to meet a ghost from her family’s past in a dream. According to the lore, the artist had originally delivered a complete manuscript, a much longer book stretching to six hundred pages; Fantagraphics proposed to put it out in two volumes, with a brief interim. As of a February 2017 interview with Comics Journal, Ferris sounded optimistic that the concluding book would appear that October.

Fans waited. And waited. The plaintive Reddit thread “My Favorite Thing Is Monsters—Will We Ever See Book Two” noted a string of phantom release dates from 2018 to 2023; as a bimonthly comics critic during part of that time, I salivated over the first such announcement, only to see the title quietly drop off the slate. Behind the scenes, a dispute was emerging over missed deadlines, the nature of the cut pages from the ur-manuscript, and whether the publisher was even entitled to put out a second volume at all, culminating in the dispiriting Fantagraphics Books, Inc. v. Ferris. Was Book One merely a monstrous abbreviation of a project that would never see completion? Was the whole thing . . . cursed?

MIRACULOUSLY, BOOK TWO IS HERE, and it picks up the plot right after the last page of its predecessor, with no bad vibes—a profound statement or sly joke about the timeless nature of the strongest art. It’s still 1968; Rosemary’s Baby (another cursed work) hits theaters; anti-war protests erupt in Hyde Park. Anka’s blood-soaked fate lingers over these pages, and Karen hears a final harrowing recording about her beloved late neighbor’s life in Germany. A dreadful secret from Deeze’s childhood comes to light, and his dual role as vicious thug/gifted magazine illustrator makes him a true art monster. Yet this follow-up is more freewheeling, less claustrophobic. It gives ample airtime to intriguing tertiary players from the first act, such as Franklin (the black “Frankenstein trans kid” Ferris dreamed up long ago) and Jeffrey “The Brain” Alvarez, a conspiracy theorist who writes unpublished science fiction and keeps a watchful eye over Karen as Deeze sinks further into his life of crime. Ominous figures and details—born-again cultists, eerie architecture, a cloaked druid who tails Karen early on—turn out to be red herrings. Ferris delights in underground passages, insane tchotchkes, a room decorated with garish clown paintings. Deeze expertly dissects Edward Hopper’s Nighthawks, explaining how the word fragment “PHI” on the diner’s facade alludes to the golden mean, the secret principle behind the painting’s magic. Embedded in Ferris’s more-is-more aesthetic, we sense, are hidden engines that animate Monsters on a subliminal level.

With her hard-nosed snooping and kid’s-level view of the urban landscape, Karen has drawn comparisons to Harriet the Spy. Author Louise Fitzhugh was a lesbian (Ferris has described herself as bisexual), and eleven-year-old Harriet has become a queer icon. Karen Reyes struggles with her queerness in Book One; here, more happily, she meets Shelley, a like-minded monster-mad girl, and the two start a religion-of-two called EGOTBU, for Eternal Guild of the Benevolent Undead. (Bonus: Shelley has a key to the cashboxes of all the pay toilets in the city, giving them easy access to loot.) After watching The Picture of Dorian Gray with Shelley, Karen takes her to view the gruesome titular painting, showing what suave D.G. really looks like. It was done for the 1945 film by Ivan Albright, and he kept adding to it over the years as it hung on the museum’s wall. Ferris reproduces the festering canvas in multicolored ink: the secret self, made visible.

In 2019, after the success of Book One, Ferris contributed a comic to the groundbreaking anthology Drawing Power: Women’s Stories of Sexual Violence, Harassment, and Survival, edited by the late Diane Noomin. Doing press for Book One, Ferris was repeatedly asked why it took her so long to produce her first comic, at age fifty-five. (“It was a mystery!”) She recalls her early love for everything from horror comics and Mad magazine to Batman and Aubrey Beardsley. Why had that obsession suddenly vanished? Then Ferris hits on a screen memory, in the Freudian and literal sense. On a long-ago trip to visit relatives, she excused herself to watch a Mr. Magoo TV special. Someone came in and closed the folding door—a “person who had repeatedly subjected me [and other cousins] to sly, sexually oriented brutalities.” On that day, her association to all comics was “poisoned.”

“The simple expressive lines that I’d once loved became fused with betrayal and cruelty,” she writes, under a phallic close-up of the vision-impaired Magoo’s nose. They were “deceptive ciphers resembling pain.” She recounts that when creating Monsters, “I found myself using a cartoonier style when I needed to talk about difficult things . . . especially those revelatory moments when a character confronts abuse, fear and shame.” Ferris muses that, in creating My Favorite Thing Is Monsters, she was either building a bridge back to her early, pure love of comics—that time before the screen—or else comics itself had “scritchy-scratched” its way back to her.

Her Drawing Power comic defines love as a “monster,” depicting a fanged Ferris-as-Karen sweetly embraced by a manticore, safe at last. The ending of Book Two, after a frantic chase and shocking family revelation, initially felt hasty to me, as though Ferris had hit fast-forward, ushering Karen into whatever existence awaits off the page. But her stunning last words are the title itself: My favorite thing is monsters. They ring true, for Karen is Ferris, and this eight-hundred-page saga—once her endlessly reworked portrait, then the exact trigger for the return of the repressed—has become her way to cast out demons she forgot she even had.

Ed Park is the author of Same Bed Different Dreams (Random House), a finalist for this year’s Pulitzer Prize.