In a recent T: The New York Times Style Magazine story extolling the virtues of boxing films (classic and contemporary), Benjamin Nugent points out that every example of the genre involves a comeback, against all odds. The protagonist pulls off an upset victory in the ring and lives to fight another day.

His point is well taken, and true for most pugilistic films, but he fails to mention one notable exception: John Huston’s 1972 film Fat City, based on the debut (and to this day only) book of the same name by Leonard Gardner.

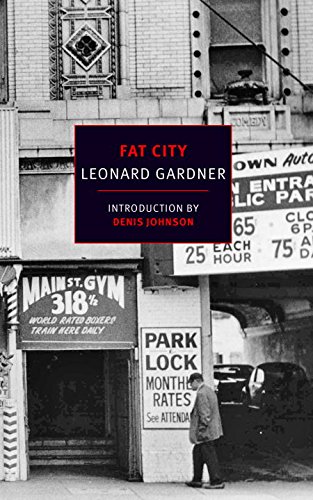

Set in the sleepy central California town of Stockton, off the San Joaquin River delta, Fat City, originally published in 1969 and now being reissued by New York Review Books Classics, follows two amateur boxers: Billy Tully, a hard-drinking transient who is young by most standards but past his boxing prime, and Ernie Munger, who is just starting out and full of promise.

Gardner, who also penned the screenplay for Huston’s film, captures the cyclical despair of Tully, an almost-thirty has-been, whose wife left him, and who lives out of a suitcase in run-down hotel rooms (Stacy Keach plays Tully in the movie). Munger—in his late teens in the book, and played by a handsome Jeff Bridges in the film—is working out one day at the local YMCA. He ends up casually sparring with Tully. Seeing promise, Tully sends him to see his old manager, Ruben Luna, who runs the Lido Gym, a ramshackle ring for middleweight fighters. (This is one element that’s true of every boxing story: the unshakeable fight manager who also serves as an unofficial life coach and motivator-in-chief.)

Gardner’s writing style is stripped down to essentials, the sparseness of his prose exposes how well crafted his individual sentences are. He expertly evokes a cinematic picture of mid-twentieth-century California on the outer fringes:

Days were like long twilights in the house under the black walnut trees; through untrimmed shrubs screening the windows the sun scarcely shone. It was a low, white frame house with a sagging porch roof supported by two chains that through the years of stress had cracked the overhang of the main roof where they were attached, pulling it downward at so noticeable an angle that everything—overhang, chains, porch roof—appeared checked from collapsing by nothing more than the tar paper over the cracked boards. Inside, from other chains, hung light fixtures that never totally dispelled the murkiness of the rooms. At the back of the house, Ernie Munger slept late, stirring only briefly to the chatter of water pipes, subsiding back to sleep and waking at the banging of a frying pan, eating breakfast in his dreams before waking up at noon.

Tully and Munger are more hopeful characters than the Midwestern drifters one encounters in the early works of Denis Johnson, who writes the introduction to this new edition of Fat City. In many ways, Johnson is the rightful heir to Gardner’s prose style, and he unambiguously alludes to the importance of Gardner’s influence: “Between the ages of nineteen and twenty-five,” he writes, “I studied Leonard Gardner’s book so closely that I began to fear I’d never be able to write anything but imitations of it, so I swore it off.”

The best scenes in the book are ones that capture young pugilists at play: Gardner takes you ringside, but also behind-the-scenes, to illustrate the intense determination a young fighter needs. Very often, he’ll end up losing the fight anyway, without remembering exactly what happened—or even who won the fight (and how).

Wes Hayes had not lasted a round. Hurling himself forward with a right swing, he had run into a cross to the jaw. Then wildly pummeled, he had crouched against the ropes with his gloves cupped before his face, unsure of what to do and so merely waiting for his opponent to stop hitting him so that he could start hiting again himself. But when the punches ceased he looked up to find the fight had been stopped. Mortified before so many witnesses, he had shaken his head as though truly dazed.

At the book’s start, Tully has been sidelined from fighting for a host of reasons, including drinking, divorce, and debt, but begins to train again at the Lido Gym. By day, he works in the fields, picking (then working his way up to checking) produce in California’s rolling green hills, essentially Steinbeck country a generation after The Grapes of Wrath, if you swap out Salinas for Stockton.

Tully goes on to win his first comeback fight, then drifts back into his old, undisciplined habits—this time on account of his break up with Oma, a barstool neurotic, soap-boxing her way through life on a liquid diet of dry sherry at the local saloon (played by the Oscar-nominated Susan Tyrell in the Huston film). Oma eventually becomes Tully’s foil—a repeat of his destructive relationship with his ex-wife—and the reason he goes on a bender once more.

Tully and Munger meet up again on the migrant-worker wage line one afternoon in the center of town. Munger is trying to earn a few more dollars to provide for his wife and expectant child; Tully, meanwhile, is there just to make the weekly rent and stay above water. Gardner paints a dire picture of a chance encounter amid the backdrop of bone-wearying agricultural work in the fields.

In the midst of a phantasmagoria of worn-out, mangled faces, scarred cheeks and necks, twisted, pocked, crushed and bloated noses, missing teeth, brown snags, empty gums, stubble beards, pitcher lips, flop ears, sores, scabs, dribbled tobacco juice, stooped shoulders, split brows, weary, desperate, stupefied eyes under the lights of Center Street, Tully saw a familiar young man with a broken nose.

Although they are both tied to the Lido Gym, they drift in and out of each other’s lives for the majority of the book. Their fateful reintroduction, in the picking fields, finds them almost back to where they started, albeit more roughed up, both of them (but especially Tully) quailing “before the emptiness of the day ahead.”

It seems neither Tully nor Munger have a bright future, in or out of the ring. Their fighting dreams are always fleeting, beyond reach. The emotional and physical toll boxing has on these amateur fighters—all somewhat desperate characters—is not measured in the fame and glory most boxing books or films portray, but instead registers in each other’s company as comfort through the highs and lows and everyday life, everyday existence.

Gardner’s characters stay with you, for good or ill, each one a cautionary tale. And although we continue to root for young Munger we can see what would happen to him if he followed Tully’s path:

On the days and nights that followed and became indistinguishable in his memory, he pined for Oma and abhorred his unfathomable stupidity. The thought of existing alone produced instants of vertigo. . . . Without Oma he felt incapable of anything. He could not bear the thought of training, not only because of the effort he could never summon from himself now, but also because the idea of fighting was disorienting in its repugnance. He felt that everyone at the Lido Gym was insane. . . .

At noon the next day Tully ate a bowl of oatmeal covered with sugar. He drank coffee sweet as syrup and went on to the Harbor Inn for a glass of wine. Later he bought a fifth and set off to find a warm place to drink it. A cold wind was scuttling papers along the gutters. Dark clouds lay over the delta fields visible to the west beyond the tanks of the gas works that rose from green nettles and fennel and wild oats on the bank of Mormon Slough. In the reeking entrances of vacant storefronts, men in overcoats, sitting on flattened cartons, looked out with rheumy eyes.

The book’s conclusion differs from Gardner’s screenplay, but it is easy to see why it doesn’t matter—there is no happy ending either way. The story of these two characters, and the eccentrics they come across in the dive bars and greasy spoon diners around Stockton is hard all the way through. But this never stops Gardner’s characters, summed up by Johnson as “men and women seeking love, a bit of comfort, even glory—but never forgiveness—in the heat and dust of central California.” Fat City might not feature a comeback, but its portrait of failure and human frailty exudes a deep sense of perseverance, even of power.

J. C. Gabel is a writer, book editor, and small publisher living in Los Angeles. He is originally from Chicago.