During the drained-out years of the 1960s and ’70s, when there was no public outlet for a frank conversation, Homo sovieticus would gather with friends in a Moscow kitchen, identical in shape and size to those in concrete apartment blocks all over the USSR. The radio would be turned to full volume, drowning out loose talk that might otherwise escape through pre-fabricated walls. The décor would display only muffled colors—the mediocre browns and grays of the Soviet everyday. On a shelf: a three-litre jar of birch juice, pickled cucumbers and a gray salami procured for a special occasion. The clothing worn by this gathering would be especially lacklustre; frumpy dresses, crummy shoes and in winter, the ubiquitous felt cap and shapeless overcoat. One friend might arrive from a shift as a stoker in a boiler room, another from work as a janitor in a communal apartment on proletariat street—bottom-rung jobs that satisfied the state’s requirement for citizens to be employed, and little else.

What dreary and impoverished lives, we might say! But in the cramped Moscow kitchen, the souls of Homo sovieticus would be nourished by a great feast of ideas, obscenities, and shared memories.

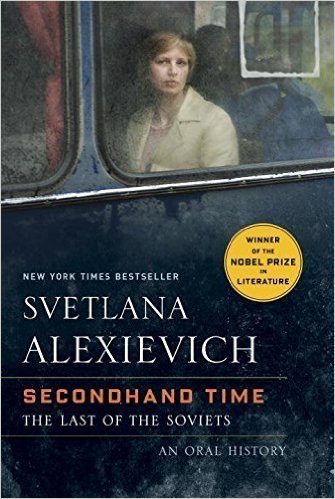

In Secondhand Time, the latest work of non-fiction by Nobel laureate Svetlana Alexievich, the frank and harrowing confessions of Homo sovieticus are recorded for posterity. By way of street interviews and a wealth of candid kitchen conversations, Alexievich sounds out disenchanted voices from across the former USSR. Here is an oral history rooted in totalitarian experience, bound to the trajectory of socialism in Russia from the time of Stalin until its implosion, and succession by an embryonic capitalist society, in the 1990s. The disequilibrium and upheaval of this era is captured in Alexievich’s hard-hitting book. Yet the poignancy of Secondhand Time lies in its grounding of a brutal historical narrative in the contours of domestic and interior experience; in the intensely personal reflections of individuals swept up in the socialist drama.

A Marshal of the Red Army hangs himself from a Kremlin radiator, a Soviet pensioner burns himself alive on his own vegetable patch, and the body of a junior police sergeant is returned from Chechnya in a wet and leaking coffin. These are some of the tragedies that serve as points of departure for the chorus of voices in Secondhand Time. They appear alongside distressing accounts of Tajik migrant workers, Armenian refugees, frontline veterans of the war with Nazi Germany, and victims of the new poverty engulfing Russia in the wake of economic collapse.

Taken together, this catalogue of human suffering rebuffs any notion of a grand Soviet legacy. The onslaught of details recorded by Alexievich emphasize a cruel and Spartan past. An architect recalls her mother returning from exile in the farthest reaches of Siberia with just “a zinc roasting pan . . . two aluminium spoons and a tangle of torn stockings.” A doctor recounts learning to fly a plane in the Komsomol with “handmade wooden planks wrapped in burlap” for wings. And a former worker on the Abakan-Taishet Railway describes a seven-day journey to the construction site, in freight cars with “two levels of hammered-together bunks, no mattresses, no linens, and your fist for a pillow.” It was exactly this kind of detail that remained absent or distorted in Soviet official life.

If communal living in the Stalinist era was part of the Great Terror—a communal apartment was a place where neighbours would eavesdrop and inform on each other—the advent of single family housing in the later Soviet period offered citizens a sanctuary from the overbearing state. The two-bedroomed Khrushchyovka apartment, named after the administration of Nikita Khrushchev, was the unlikely setting for the explicit dialogues recorded in Secondhand Time. In the 1960s and ’70s, a great swathe of Soviet society found a measure of privacy in the Khrushchyovka kitchenette. This was the heyday of samizdat, when “books replaced life,” and ideas previously confined to desk drawers could be circulated amongst trusted friends. In Secondhand Time, Alexievich gives us an insight into the intensity and agency of this milieu. One of the narrators describes handling a book like “a secret weapon,” picking it up in the morning from a station in Moscow and reading it in one day before handing it back “on a train passing through town.”

With increased freedom of expression under perestroika, this clandestine activity was swept into the realm of public life. Readers of dissident literature became frenzied participants in momentous political events, culminating in the defense of the reformist government’s White House during the hard line coup of 1991. These were optimistic times, euphoric even, when Soviet people believed in things like humane socialism, freedom, and change.

As the chorus in Secondhand Time testifies, it was not just heroes of the Soviet Union and Communist party apparatchiks who lost prestige when the monolith crumbled. All those who adhered to Soviet values, whether they served the regime or marched for change, were thrust into a new and bewildering context in the freewheeling 1990s. And that included the large and diffuse intelligentsia, the “kitchen dissidents” who were dismayed to find the ideals of literature trounced by greed and cold hard cash.

Who were these brazen capitalists? With their “gold rings and magenta blazers” they were a new breed, and their desires jarred with the genteel and ascetic tastes of the intelligentsia. “Instead of your samizdat poems, show me a diamond ring, expensive labels…” an advertising manager tells Alexievich. She is inspired by a new vocabulary of “offshore accounts, kickbacks, [and] barters,”and is happy to see the “entire former repertoire of gentlemanly charms”—the samizdat and whispered kitchen conversations of the intelligentsia—fall by the wayside.

Secondhand Time captures the anguish and disenfranchisement of the “kitchen generation,” who had looked upon themselves as the nation’s conscience in the giddy years of perestroika. In the aftermath of rationing, economic “shock therapy,” and hyperinflation, this enlightened strata of society had grown calamitously poor.

Alexievich pays her respects to their vanished discursive culture, wielding the kitchen conversation to startling effect. Crucially, she draws her protagonists from beyond the social circles of urban intelligentsia. Alexievich spent a number of years travelling throughout the former USSR and many of the memorable dialogues in Secondhand Time take place in squalid villages and provincial towns where the material deprivations and minor satisfactions of Soviet life linger on.

“You won’t refashion Russia in a Moscow kitchen,” observes a documentary filmmaker in the penultimate section of Secondhand Time. The expression reveals the gulf between Muscovites and those inhabiting the land of Russia proper. The filmmaker tells the story of a provincial worker who abandons her husband, children, and home for the love of a prisoner once awaiting execution, now serving a life sentence in the Russian north. Her actions shed light on a wider “culture of pity” that manifests itself in intimate correspondence between village women and the habitual offenders inside Russia’s penal system. The phenomenon of individuals writing hundreds of letters to prisoners is never entirely explained. The style of this book is to let the welter of detail speak for itself. Alexievich is content to stitch together many subjectivities and to interject only sparingly with authorial comment. She has remarkable confidence in the unguarded testimony of her interviewees—in the sheer potential of discourse and storytelling to address a historical moment. If the resulting mosaic is sometimes telegraphic or obscure, it is effective nonetheless. These are the narrative’s embedded mysteries, the way eavesdropping on someone else’s conversation combines unfamiliar references with recognizable emotions and motivations. “I don’t ask people about socialism, I want to know about love, jealousy, childhood, old age” says Alexievich at the start of Secondhand Time. Their answers contain the vanished intimacy of an entire Soviet generation.

Thomas Dylan Eaton has contributed essays and fiction to publications including Afterall Journal, Parkett, The White Review, and Ambit Magazine.