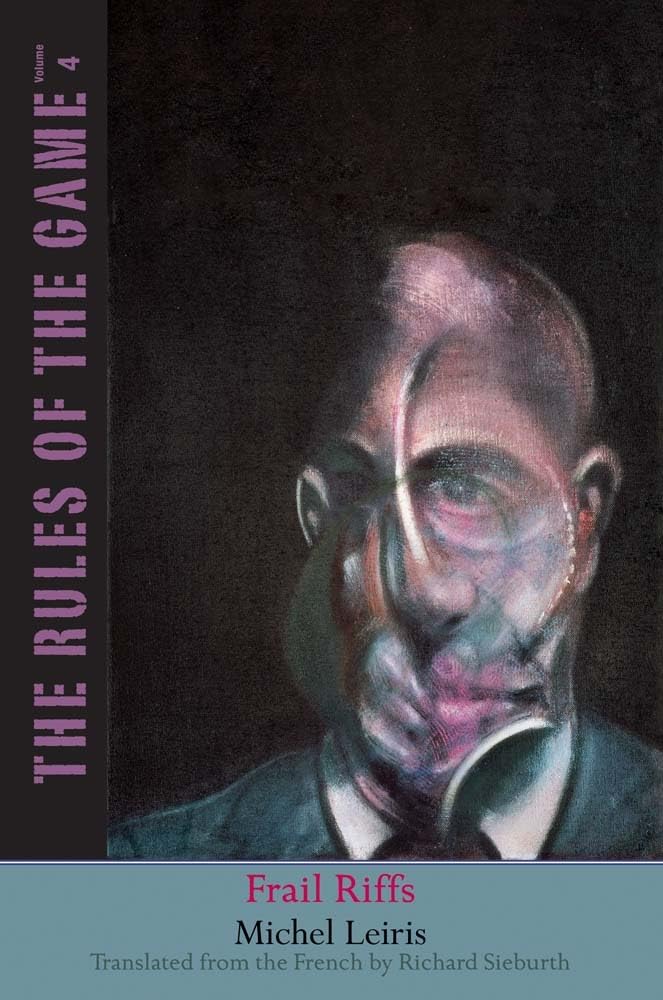

MICHEL LEIRIS WAS A SMALL, polite French man who stayed alive for most of the twentieth century and wrote a deliciously dense memoir in four bricks called The Rules of the Game. The final chunk—Frêle Bruit, whose title has been translated by Richard Sieburth as Frail Riffs,rather than the more straightforward “faint noise”—is now finally available in English. This memoir project spans the years 1948 to 1976, which is roughly the middle of Leiris’s writing career. There were, in fact, memoirs published before and after this project, and a massive set of journals (only available in French as of now) that stretch across his life from young adulthood right up to death. Taken in sum, almost all of Leiris’s writings qualify as what he called “essais autobiographiques.”

Leiris often reminds me of artists like Chris Marker who work across disciplines and scatter their thoughts hither and yon, poets who put their work into different containers precisely to fight against a quick summary of their intentions. Leiris gestures at least once to the fact that this memoir—“too waxed, too polished”—is as much an act of poetry as it is a form of reporting. “There are afflictions that nothing can cure and that only poetry can help you come to terms with,” he writes. There is no sustained argument or narrative to Frail Riffs, which deals as much with childhood as it does advancing age, and cycles through Leiris’s interests without feeling a need to connect them all. Fans of Romeo and Juliet will enjoy this riff, which appears in one of the many stand-alone entries: “Scandalous Mercutio, talker of nonsense, antihero animated by no spirit of sacrifice nor by any devotion to a cause however just or unjust, but willing to risk it all for the mere hell of it.” There is the recurring sense that the pain of writing is also a secondary gain for him, and the drama of the process is partly the point:

Sort out, caress, marry the words together; at times dissect them, twist them, break them apart. Not to seduce them or mock them, but as a way—needless to say, an illusory way—of appeasing, of turning around, of putting a stop to something inevitable. As a way—despite all its weaknesses, all its blemishes, all its lacunae—of conveying the fact that somewhere within ourselves it still might be possible to get a grip on things.

As his longtime translator and champion Lydia Davis told me recently, Leiris is “seeing something that we’re not seeing and he is telling the truth as he sees it.” Riding along with Leiris is nothing like reading the contemporary autofictionalist, in that the self disappears into a process of minute sensing and detailing that the self happens to be the steward of. “It’s self-centered, literally,” Davis said. “But it’s not egotistical in a bad sense, partly because he is so modest, really, and he’s regarding himself almost objectively as an object of interest.” What distinguishes The Rules of the Game—especially the intense fragments of Frail Riffs—from the other Leiris work is how distinct and dissimilar the various pieces are, and how unexpectedly cheerful it all is.

Its poetic torque, how it pulls the reader into a constantly regenerating consciousness with a psychedelic alternation of clauses, turns language into something like a tonal field. Leiris scholar James Clifford described Leiris’s sentences as “elaborate, careful, self-limiting performances,” while Davis called them “deliberate overload.” The slow cadence and constant deferment in Leiris’s language embodies the nature of his thinking, which can be obscure even when the observation itself is not. The Leiris sentence is very much about the time it takes to reach the end. Along the way there are many thoughts. The way these thoughts are chained together into one sentence is as important as the thoughts themselves, indicating that this is how thoughts lived inside Leiris, and any attempt to shorten or recombine those thoughts would make it someone else’s thoughts. This is one from Fibrils, volume three of Rules of the Game, about his Aunt Claire’s house:

Apart from its exterior, which I did not think, incidentally, I would remember well enough to recognize it right away, what I recall about this house is reduced to very little: the calm and order that reigned in the parlor, whose candy-box preciosity did not conform very well with the robust beauty of its inhabitant, who was created on the scale of the lyric-theater stages on which she appeared; the presence, in a good spot in this excessively mincing parlor, of a glass-fronted cabinet where my aunt kept objects of which I would be incapable today of drawing up an inventory—even if limited to general categories—but of which I know that several at least related to her life in the theater.

LEIRIS WAS BORN in 1901, into a bourgeois family and had brief professional aspirations that were drowned out by the siren calls of jazz and Surrealism. He became a poet and an active member of André Breton’s Surrealist group in Paris. His first book, Simulacre, was published in 1925, a collection of poems illustrated by one of his mentors, André Masson. Leiris rarely leaves the heart of bourgeois comfort, which complicates his commitment to the larger idea of revolution—more specifically, to the people of Cuba and the students at the heart of the May 1968 actions in Paris. (As he puts it in Frail Riffs, “I’m just a poor devil and hardly a guerrillero when it comes to moving from the plane of ideas into the rugged terrain of action.”) In 1926, Leiris marries Louise “Zette” Gordon, presented as the sister of prestigious art dealer Daniel-Henri Kahnweiler, though she is eventually revealed to be Kahnweiler’s wife’s illegitimate daughter.

In 1929, Leiris broke with the Breton gang and joined the upstart Surrealist journal Documents, founded by Georges Bataille, Georges Henri Rivière, and Carl Einstein. (Though recently compiled in a handsome two-volume French edition, Documents remains largely untranslated into English.) It is in the office of Documents that Leiris makes a decision that changes his life completely, if also somewhat casually. He meets the ethnographer Marcel Griaule, who invites Leiris along on a mission to Dakar and Djibouti as a stenographer and documentarian of sorts. Though he has absolutely no training, Leiris likes the idea, saying later that he became “weary of the life of literary Paris between 1925 and 1930.”

In an essay published in Documents at the end of 1930, titled “The Eye of the Ethnographer,” Leiris offers some explanation for why he is taking off on this particular adventure, in a sentence that hints at the rock-climbing walls of clauses he will be building.

A research trip undertaken in accordance with the standards of ethnography—such as the expedition from Dakar to Djibouti in which I am planning to take part, under the direction of my friend Griaule—should help to dissipate no small number of these errors and, consequently, to undermine a number of their consequences, including racial prejudice, an iniquity against which one can never struggle enough.

Leiris records 647 diary entries during the years of the excursion across several African countries and makes thousands of index cards to describe each of the artifacts the team is bringing back, whether they have the moral or legal right to do so. Phantom Africa was published in 1934, much to the displeasure of those who brought him, as well as to the French government. Leiris makes no strong ethnographic claims and spends as much time doubting the project as he does describing his time among the Dogon people, who he knows will never accept him. “The life we are leading here couldn’t be more flat and bourgeois. The work is no different in essence from work in a factory, firm, or office. Why does ethnographic inquiry often make me think of a police interrogation?”

Despite his skepticism and friction with Griaule, upon his return to Paris, Leiris became the codirector of the Département de l’Afrique noire at the Musée de l’Ethnographie (renamed the Musée de l’Homme in 1938). In 1943 he was officially named to the CNRS (Centre National de recherche scientifique), which pays some of his salary at the museum; he is further promoted as a researcher affiliated with the CNRS in 1961. After his important fieldwork is over (notably in Martinique, Guadeloupe, and Haiti), during the period when he is writing Frail Riffs, he is primarily concerned with “museology”—in 1967 he publishes (with Jacqueline Delate) Afrique noire, La Création plastique, on which he has been working for eleven years. The same year he organizes (again with Delate) an exhibition at the Musée de l’Homme, Arts primitifs dans les ateliers d’artiste. This is followed by the exhibition (conceived in May 1968, opening in the fall) on Passages à l’âge d’homme. His most important writings of the late ’50s and ’60s were published in Cinq études d’ethnologie in 1969. He officially retired from the Musée de l’Homme in 1971, but they let him keep his basement office.

For the outside literary world, his ethnographic work doesn’t really appear as the topic of his books again. In 1939, he published what is technically his first memoir, Manhood, though the index cards and diaries of Phantom Africa have become part of his standard practice. It is this book that makes his name in France, though it is years before the Anglophone world discovers it. The book inspires both Sartre and Walter Benjamin, and remains a model of fragmentary revelation. Its main characteristic, much more surprising in 1939 than now, was Leiris’s frankness about his failings and a sort of ambient anxiety, often around sexual energy.

After explaining that whorehouses and museums are linked by a common “frozen quality,” he reveals that a childhood penis inflammation has complicated his sexual life ever since: “I am incapable of distinguishing this morbid turgescence from my earliest erections, and I believe that initially the erection frightened me because I took it for another outbreak of the disease.” There is a lot of this generalized erotic terror as well as memories of his brother threatening to remove his appendix with a corkscrew. When he begins The Rules of the Game in the ’40s, with Scratches, he is resetting his tone a little. He increases the lexical weight of the project but also strips it of its pathos. For someone who had a generally pessimistic bent, and talked so often of his intermittent impotence, Leiris becomes more sanguine as he ages, almost against his own tendencies. By the time he reaches Frail Riffs, he has become a dealer and a shuffler of cards, presenting 167 individual entries, some complex essays, others short and silly poems that use words all beginning with the letter P.

The density of a Leiris text is both an obstacle for impatient readers and the prominent condition of its rewards. Lydia Davis, who translated the previous three volumes of Rules, writes in the intro to Fibrils, that one of Leiris’s main “preoccupations” was language “as the raw material of poetry; the mysteries of language; the sounds of words, taken in themselves; the elusive and personal meanings of these sounds and of words themselves; private language versus shared language; language as connection to others; the discoveries possible through language; the failure of language.”

Sometimes, Leiris rummaging through words is a private enough affair that the reader has trouble joining him. Recalling names of imaginary characters he invented with his brother, Leiris parses “Bob Singecop” and “Elephantinonde” at length, analysis that leaves me stranded. Did Leiris love his brother? Resent him? Sometimes choosing to discuss a “bizarre syllable” feels less like an investigation and more like an evasion. When Leiris writes that “Elephantinonde” is “nothing but a word” that also “remains an entire world unto itself,” he recalls the other famous French pilot of rapid metonymy, Proust. But Leiris is less interested in emotion than Proust, which leaves some of his glosses feeling more technical than revelatory.

You may have noticed that Davis did not list “narrative” or “story” as one of the Leirisian preoccupations, which is probably why Leiris is less likely to be found on syllabi than Proust, who Davis has also translated. The two are intimately related for Davis, who told me that Leiris’s “syntax actually did prepare me for translating Proust’s elaborate syntax.” Nobody, not even Proust, has been able to slow down the spin of time like Leiris, who is able to slowly scrub the needle of language back and forth across moments until they crumble like the wax of his father’s cylinder gramophone. This monomaniacal pursuit of consciousness through language itself has obvious limits, in that Leiris writes in such a way that you can only identify people through the language, rather than character or setting or personal quirks. I know little about how the people in his life moved or looked or behaved or sounded. Sieburth, as gifted a medium for Leiris as Davis, wrote in 1993 that The Rules of the Game had taken “the literature of confession beyond narrative, beyond its residual affinities to the novel, and moved it toward the condition of music.”

One of the absolutely most delightful and Leirisian pieces ever is his long entry here on the nature of “the marvelous,” a winding and thick meditation that refuses to act much like an essay, in that Leiris has no intention of building anything as pedestrian as a definition. Instead, he simply accrues a series of people and artworks and “examples” that summon the marvelous for him. After many pages of trying to determine how far from the marvelous the “supernatural” really is, Leiris turns abruptly to Che Guevara. If you are wondering why you might want to sift through all the juvenilia and puzzle pieces of Frail Riffs, I would suggest that sentences like this make it more than worth it: “In his clearheaded and feet-firmly-on-the-ground fashion, breathing in the air of his times despite his asthma, Che Guevara was certainly not thinking of the marvelous when he spoke of how the extraordinary could one fine day be transformed into the everyday.” There has been little discussion in this essay on the political, which lurks closer to the surface with Leiris than you expect. But the actions of May 1968 are both ghost and presence here, and Leiris tells us that “the marvelous of the Revolution” has the ability to demonstrate “the sudden feasibility of a series of accomplishments previously thought to be lunatic.”

After several of the most bourgeois pages imaginable are spent on the topic of where he and Zette will lodge their dog, Puck, when they go on vacation, Leiris comments on the slogans of May ’68. He approves of “NO MORE CLAUDELS,” a strike against the French sculptor he describes as a “mammoth gymnast of eloquence, this pride of the bourgeois status quo.” One wishes there was a Leiris column now on the encampments, not least because of how he begins this entry, with the slogans of his own: “Let nothing petrify. Let nothing freeze. Protest without end.”

Sasha Frere-Jones is a writer and musician from New York. His memoir, Earlier, was published by Semiotext(e) in 2023.