Joel Dicker, a 27-year-old Swiss novelist, is the talk of the town in his native city of Geneva. Dicker’s second book, La Vérité sur l’affaire Harry Quebert (ed. Fallois/l’Age d’Homme, Sept. 2012) has won three major literary prizes, including the novelist’s award from the Académie française, and was long-listed last year for France’s Prix Goncourt. At the Frankfurt Book Fair last fall, Harry Quebert was a sensation: one observer compared the buzz surrounding the book to that of Stieg Larsson’s Millennium series. That Dicker is young, handsome, and managed to dethrone Fifty Shades of Grey on the bestseller list of Amazon.fr surely didn’t hurt, and to this day, Harry Quebert remains among the site’s top-selling books. The fact that the novel, a murder mystery set in New York City and the American Northeast, hasn’t been picked up by an American publisher more than a year and a half after its release is something of a mystery itself.

La Vérité sur l’affaire Harry Quebert, or “the truth about the Harry Quebert affair” is a classic whodunit with literary aspirations. The novel’s protagonist, Marcus Goldman, is a successful young writer juggling newfound fame and a debilitating case of writer’s block in the months following Obama’s election in 2008. When Goldman’s mentor, a novelist and college professor named Harry Quebert, is accused of having murdered 15-year-old Nola Kellergan more than thirty years earlier, Goldman, convinced of Quebert’s innocence, decides to investigate. In the New Hampshire town where Quebert lives, Goldman gathers interviews, photos, and newspaper archives in order to reconstruct Nola’s final hours in a dark forest near the ocean. Along the way, Goldman’s rapacious literary agent convinces him to turn the ordeal into a book, which, after much hand wringing about the hardships of the writer’s life, he does. Working on the book magically cures Goldman’s writer’s block—but it comes at Quebert’s expense.

With its lively plot and smart, detached commentary, the first third of the book is a thoroughly engaging look at the fickle and competitive side of the New York publishing world. Coming off the heels of a bestseller, Goldman quickly learns that writing is as much a business as it is an art. Six months after his book is published, Goldman’s notices that “the fan mail became rarer and rarer, and in the streets, people approached me less. Soon, those who recognized me started to ask, ‘Mr. Goldman, what will your next book be about? And when will it be out?’” Goldman’s agent and publisher don’t hold back when Goldman comes to them without having written so much as a page of new material. “You’re making us lose money!” the head of his publishing house barks, giving Goldman six months to write a new book or forgo his five-book contract.

As pressure intensifies for Goldman to produce, Harry Quebert turns into a noir thriller, taking the reader through a circuitous investigation into Nola’s death. Before long, Goldman—and Dicker’s—literary ambitions begin to blend with this inquiry. When Goldman makes his first big breakthrough and learns of an illicit romance between Quebert and Nola, the story becomes a novel within a novel. Suddenly, we’re reading excerpts of Quebert’s most famous work of fiction, The Origins of Evil, and taken through flashbacks laden with American literary references. With her girlish good looks and provocative manner, Nola is an obvious stand-in for Lolita, while Quebert plays a sad, downtrodden Humbert. There are Norman Mailer-inspired scenes of Goldman and Quebert boxing, and the story is set in a college town reminiscent of the setting of Philip Roth’s The Human Stain (or, more recently, Chad Harbach’s The Art of Fielding.)

Throughout, Dicker narrates in a French so plainspoken that it reads like American English.

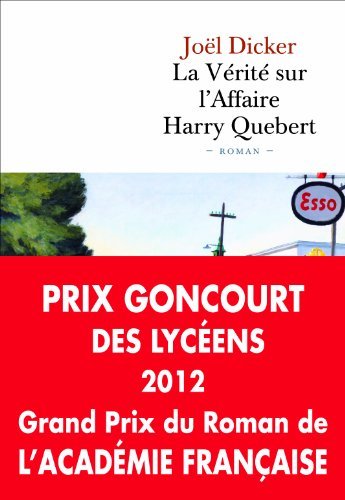

Dicker appears to have set out to write the book that a French Roth might have written had he gotten a grant to fictionalize the American Northeast. Much of Harry Quebert is set in a diner, and the novel tends to take Edward Hopper’s representations of Americana a little too seriously. (A Hopper diner graces the cover of the paperback.) As is apparent in Goldman’s reflections on his childhood, Dicker is trying to package small-town American life for European consumption:

“I explained that I was born at the end of the 1970s in Newark to a mother who worked at a department store and an engineer father. A middle-class family, good Americans. An only child. Childhood and adolescence were happy despite above-average intelligence. Felton high school & Giants fan. Braces at fourteen. Vacations at an aunt’s place in Ohio. Grandparents in Florida, for the sun and the oranges. It was all very normal. No allergies, no notable illnesses to declare. Food poisoning from chicken during Boy Scout camp at age eight. Likes dogs but not cats. Sports: cross country, running and boxing. Ambition: to become a famous writer. Doesn’t smoke because it causes lung cancer and smells bad the morning after. Drinks reasonably. Favorite dish: steak with macaroni and cheese.”

Early in the novel, Quebert advises Goldman not to get devoured by his own writerly ambition at the beginning of his career. Joel Dicker could stand to take this advice. Harry Quebert is overwhelmed by its ambition—the book is almost 700-pages long—and by it’s constant borrowing from classic American fiction. Perhaps that’s what’s stopping it from getting published in the US—the themes are too familiar, and the scenery is worn. What’s more, Goldman’s investigation contains more plot twists than a game of Clue, and throughout all of it, Quebert remains in the background, doing little more than dispensing mournful lines and cryptic advice.

The novel is most successful when it stops characterizing America, the country, and instead focuses on questions about the US media and criminal justice system from an outsider’s perspective. Dicker’s observations about a crime suspect’s supposed innocence until proven guilty are well-executed and intelligent: By framing multiple men as Nola’s murderers and then absolving them, Dicker shows how unfounded suspicion can send the press on a gossip rampage. And by revealing Nola’s emotional problems, Dicker complicates the media ideal of a so-called “perfect victim.”

In his attempts to clear Quebert’s name, Goldman finds out the truth about Nola’s murder, but also learns about his mentor’s real crime—a crime perfectly suited to a struggling, desperate writer. Ultimately, Dicker’s story is about a writer who gets written, by, and for the benefit of another writer. It extends Janet Malcolm’s assertion that all journalists know that what they do is “morally indefensible” to include not just non-fiction writers but novelists. The two men part ways soon after Goldman’s book is complete.