No matter how many years I’ve spent on the proverbial couch—about fifteen, at last count—I still find myself wanting to say to my therapist “I wish I were dead inside.” The formulation is at least half joking—note, for one, that hilarious cliffhanger between the last two words—but the feeling is nonetheless both lingering and sincere. A clearer way of expressing it would be: I wish I didn’t feel pain/I wish I didn’t show pain; I wish I didn’t care/I wish I didn’t show I cared. I wish, in other words, that I were more like Kim Gordon.

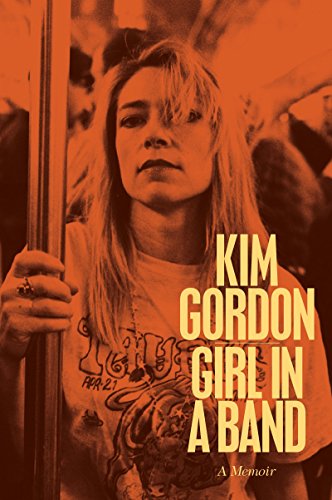

The iconic bass player in the experimental rock group Sonic Youth, Gordon has been the object of many a projective fantasy. Yet, as she writes in her appealingly melancholy, nicely open-ended memoir, Girl in a Band, she has perhaps most often been seen as “detached, impassive, or remote,” a woman “nothing could upset or hurt,” a woman who, despite her furiously dissonant music, views the world with aloof disinterest. It is this perceived deadness—or detachment, to use a less loaded term—that Gordon sets out to complicate in her book. The narrative is bookended by the dissolution of her relationship with her band-mate and husband of twenty-seven years, Thurston Moore, but this is not a memoir of divorce, exactly, nor of a life in music, though these two strands play important roles. It is, more broadly, a searching exploration of the costs of performance, particularly for women: what happens to women as they perform, not just onstage but in the world, in an environment that is still essentially misogynist and quick to turn them into either fetish or casualty. Gordon argues for the usefulness and occasional necessity of her own detachment while simultaneously revealing the ransom it can exact.

In the book’s early chapters, Gordon describes her childhood and young adulthood growing up middle class in Los Angeles in the ’60s and ’70s, daughter to an academic father and a creatively frustrated homemaker mother. Generally sympathetic but closed off—“You kept your problems to yourself and got on with life,” is how Gordon sums up the attitude—her parents proved unable to protect her from her menacing older brother, Keller: charismatic, manipulative, abusive, and, in time, diagnosed as a schizophrenic. Gordon identifies Keller’s incessant bullying as standing at the root of her blank persona: “The biggest challenge as I saw it was to pretend I had some superhuman ability to withstand pain.” In one harrowing scene, she recounts an occasion on which Keller got in her bed naked and, when she resisted him, called her a “slut.” She blames her reluctance to tell her parents about the transgression on having idealized her brother, and discusses their relationship with typical understatement: “I still struggle with the idea that I let him make me feel bad about myself.”

Examples of this attitude—of Gordon being at once affected by and yet at a remove from catastrophic events—appear throughout the book. Of a car crash in the late ’70s, she writes:

I was sitting in a driveway in heavy Southern California traffic in my old VW bug . . . when a car driving down the street bashed into a second car. I’m the witness, I told myself, and just then that same car swerved up onto the sidewalk, hitting my VW and folding it up against a wall. . . . a year later the money I got from that accident would make life in New York possible.

Fashioning yourself a mere witness doesn’t always make you one. But does participation always make you a victim? Gordon, at least, seems to have found power in maintaining distance. In her retelling of Sonic Youth’s last-ever show, after she and Moore had already separated, she explains her attempt to keep it together. A show of pain, she thought, risked being perceived as a “personal statement.” She didn’t want to be seen as performing trauma like, say, Courtney Love does. “I would never want to be seen as the car crash [Love] is. I didn’t want our last concert to be distasteful.” And in a passage that became Internet-controversial even before the book’s official release, Gordon attacks millennial chanteuse Lana Del Rey for what Gordon sees as Del Rey’s infatuation with a theatricalized self-victimization: “Naturally, it’s just a persona. If she really truly believes it’s beautiful when young musicians go out on a hot flame of drugs and depression, why doesn’t she just off herself?”

This hot blurb suggests a very ’90s attitude, one still in thrall to the credo of “4 real,” to quote the phrase that Richey Edwards of the Manic Street Preachers razor-bladed into his forearm, in an incident emblematic of the era, to convince an NME journalist (!) of his band’s commitment to rock ‘n’ roll authenticity. Generally, however, Gordon’s approach is more sophisticated. She knows that one’s persona onstage doesn’t dovetail exactly with one’s so-called real self, and she’s aware of how crucial the element of fantasy is to any performance. In an essay collected in Is It My Body?, an anthology of her nonfiction writing from the ’80s and ’90s, she writes, “People pay to see others believe in themselves.” She goes on to immediately complicate the straightforward pronouncement: “Performers appear to be submitting to the audience, but in the process they gain control of the audience’s emotions.” Elsewhere in the same collection, reflecting on Warhol, she offers a statement that functions as a kind of manifesto for her own approach: “Passivity, as a means of control through submission, implies that a pose must be taken on, an active position of being passive.”

The performance of detachment doesn’t just originate in individual psychology. It is a requirement for the entertainer, who must seduce the members of the audience while simultaneously protecting herself from them. The performance is a car crash, but contained, held in check by the performer herself, who is, after all, in the driver’s seat. As Gordon writes in “Proposal for a Story (II),” an early text work she made as part of her visual art practice in 1977, “Violent car crashes but nobody is hurt/Some violence but make believe.” It is no coincidence that Gordon calls John Chamberlain one of her favorite artists—he whose sculptures of twisted and welded car parts, at once tense and static, silently invoke previous traumas. And even when someone else is handling the vehicle, a detachment from any consequent crash might give others—and even your own self—the sense that you were choreographing the unfolding action all along. Recounting yet another violent, and violently contained, childhood memory, Gordon writes, “I was seven or eight years old when my cat was run over, and a few days or weeks later my mom let me know it was time to stop being sad, time to move on.” She adds, cryptically: “Maybe she was right.”

Must the containment inevitably crack? “I was willing to let myself be unknown forever,” Gordon admits. In fact she wanted to remain hidden. The role of enigmatic bass-player allowed her to avoid feeling self-conscious as she presented herself to others (a neat trick many more of us are able to pull off nowadays via the flattening yet oddly liberating power of tools like Instagram, with their ability to reveal us only to the extent that we allow them to). The problem, of course, is that the price of the role can be steep, especially when women try to perform it off-stage as well as on. One moving passage discusses Sonic Youth’s “Tunic (Song for Karen),” off the band’s 1990 album “Goo”—a tribute to the singer Karen Carpenter, who died of an anorexia-related heart failure in 1983. Karen and her brother’s treacly Carpenters songs were unlike Sonic Youth’s discordant rock, but Gordon saw a symbol in Karen’s disastrous life. The consequence of trying too hard to perform effortless perfection could be death. In an open letter from Gordon to the late Carpenter, she writes: “The words come out of yr mouth but yr eyes say other things, ‘Help me, please, I’m lost in my own passive resistance, something went wrong.’” Gordon continues: “How was she not the quintessential woman in our culture, compulsively pleasing others in order to achieve some degree of perfection and power that’s forever just around the corner, out of reach?”

In the final paragraph of the book, Gordon recounts a seemingly random vignette about a sexual encounter she had while parked near her Los Angeles home. The guy, a “player” she was “super-attracted to,” is shocked when she pulls away in the middle of the make-out-session. “Gee, you don’t want to fuck me right here in the car?” she imagines him wanting to ask. The scene shows Gordon in all her ambivalence: She is removed enough to put on the breaks and avoid a crash, but she’s still involved, still up for a “full-on grope,” both literal and metaphorical—with sex, with music, with art, with her own self. There’s power in distance, for sure, and Gordon gives it the respect it warrants. It seems to have served her well in many ways, and served us well, too: It’s taught us a useful, workable stance to make our lives as women in the world more bearable. But one reason I liked Girl in a Band is that it also reveals what a shitty deal this mode can end up being. If we pretend for too long that we’re dead, we may end up that way, or as good as, eternally obsessed with superintending our own arid, detached narratives. It’s better to live the story than control it.

Naomi Fry is the copy chief at T: The New York Times Style Magazine and has written for the London Review of Books and n+1, among other publications.