Crackhead, pothead, pillhead, oldhead. The suffix “-head” tends to mark a genre of name-calling. It smacks of a compulsiveness that renders your activities illicit or, at the very least, will have you deemed a space-cadet. But when you claim yourselfas a head—a sneakerhead, a Beatlehead, a hip-hophead—the suffix carries a somewhat uppity declaration of expertise, at once a boast and an assertion of membership in a particular culture or scene. Originally “hip-hophead” implied specific cultural and political commitments to the everyday survival of black people. But due to the ways the US music scene was influenced by gentrification and appropriation, evacuating hip-hop’s devotion to black culture and transforming rap into an industry synonymous with popular culture, the term now mostly denotes an attachment to the music of a particular period.

In Go Ahead in the Rain: Notes to A Tribe Called Quest, the poet and cultural critic Hanif Abdurraqib looks back to this period, the golden age of hip-hop from the mid-1980s to the early ’90s, when he discovered the music of A Tribe Called Quest as a teenager in Columbus, Ohio, and got his whoosh of brotherly sincerity, radical play, and afrocentric politics. Melding music history with personal essay, Abdurraqib recounts how the funky bass on the song “Excursions,” from Tribe’s second album, The Low End Theory, initiated him as a fan. “‘Excursions’ is the first rap song I knew that could sound good in almost any situation: in headphones, in the back- ground on any night with a thick and heavy moon hanging above your head, in a car with the windows rolled down on a hot day.” Though he played their songs on his Walkman, Tribe’s was also the rare rap music his hard-working black parents—fans of soul, funk, and jazz—would let Abdurraqib and his older brother listen to in the house. “Rap in my household oscillated between taboo and acceptable, depending on the year or the mood my parents were in, or if they’d decided to give up altogether and leave their four children to their own musical devices. Still, no matter what vibe they were on, the early albums of A Tribe Called Quest were acceptable to play in the house.”

A risk of this kind of project is the nostalgia of the longtime fan (wasn’t everything better back then?) but Abdurraqib subjects the backward-looking myths that have sprung up around the group to critical scrutiny: Was it Tribe’s jazz genealogy that gave them a “warm and vital” sound that was “acceptable” to play at home as a child? Does Tribe make the kind of smart, conscious rap music that you’re meant to “understand” rather than, say, dance, do drugs, or have sex to—with today’s so-called mumble rap the scapegoat of the latter’s physical rapture?Tracing the long career of the rap group, he admits that “Tribe became a staple around the discussion about what ‘real’ hip-hop was.” Abdurraqib admits to his own stake in the question: “This discussion becomes more common with each passing year, as hip-hop heads of a certain era age, and the genre becomes more watered down—something that happens to every genre of music as it gets older.” Still, he insists, “I am trying not to be the elder that I had access to in my days of young rap fandom.”

Abdurraqib brings specificity to what being a Tribe fan means by threading the path of the East Coast rap group with his own. Fluidly jumping around political and social context, the book moves from Jet Magazine’s decision to show the dead bodies of Emmett Till and Otis Redding to the esoteric details of sampling and copyright litigation to the 1986 World Series to the Dakota Access Pipeline protests to the death of Leonard Cohen the night before Donald Trump was elected president. Using the first person to join events that might otherwise feel merely associative, Abdurraqib weaves the 2016 police shooting of Alton Sterling—a black man killed while selling CDs in Baton Rouge—to his own memories spending time at the mall buying from CDs from a “CD Man” named Tony, as well as to the new (and last) Tribe Called Quest album, We Got It from Here . . . Thank You 4 Your Service, released three days after the 2016 election: “The map of the United States turned red on my television on November 8, 2016, and Leonard Cohen was dead but no one knew that yet, and Alton Sterling and Philando Castile were dead, and more mass shootings were happening seemingly every week, and I guess this is what a country can get away with when people consider themselves afraid.”

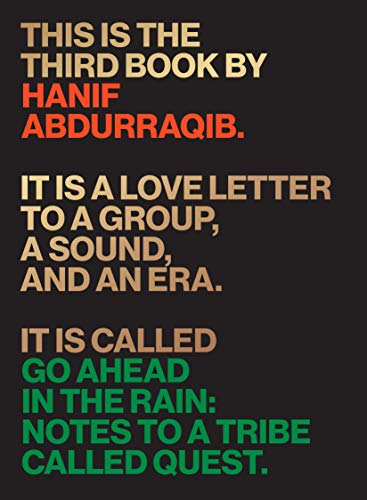

Across this historical landscape, Abdurraqib is writing to his brothers (“Notes to A Tribe Called Quest”) in an intimate voice that lends the book its vitality. The cover, designed in the Pan-African colors of red, green, gold, and black, describes it as a “love letter to a group, a sound, and an era.” Three of the twelve chapters take the “love letter” part literally by directly addressing Tribe members Q-Tip, Ali Shaheed Muhammad, and Phife Dawg, who died in 2016 due to diabetes complications. “Once, they were young and aching to go home,” Abdurraqib writes. “Now, they are old, and simply looking to vanish into anywhere but here. A blur, swallowed by a horizon.” With its reflective prose and hesitant prose, the book is ultimately less a love letter than a lament, like roses strewn on a monument, an acknowledgement that even as we admit that the tensions between Q-Tip and Phife Dawg were complicated, even as we still grieve Phife Dawg’s death, Tribe’s time has come and gone.

Part of what is being mourned in the book is that brotherhood is not what it used to be. Citing groups like Crash Crew MCs and Juice Crew rappers as precursors, Abdurraqib clings to the narrative of the 1980s rap crew in explaining Tribe’s rise and the establishment of the Native Tongues collective. Mirroring the collectivity of rap in this era, Abdurraqib tells the story of his own schooldays crew—his “boys.” “If nothing else,” he writes, “me and my crew of weirdos understood our way around a soundtrack.” They had jokes, they liked music, but they didn’t fight. Abdurraqib takes great pain to emphasize that they were not the cool kids and they were not a gang, though he admits that the latter distinction has to do with race, assumptions of violence, and fashion. “The difference between a gang and a crew sometimes boils down to reputation or intention,” he writes. It is not so much that the idea of the massive crew like Tribe has fallen away but that they have been replaced by tighter and sleeker groups like Migos and Rae Sremmurd or loose and dynamic collectives like Odd Future and Young Money. One reason for the contemporary lack of rap groups might be because of the backlash of what Abdurraqib calls “gang hysteria:” gatherings of young black people are increasingly criminalized, that is to say, the difference between a gang and something else is entirely up to police discretion.

Even as Abdurraqib tries not to play into the idea that one type of rap is better than any other, implicit in his discussion of black social life is that Tribe was the nonviolent alternative to N.W.A.’s gangster rap. Tribe was (and is) critic’s choice—rap for the socially aware, rap for the self-defined intellectual. The group even recorded a song called “The Infamous Date Rape” off of their 1991 album The Low End Theory, which Abdurraqib calls a kind of “political album that the world needed at the time.” “The Infamous Date Rape” came out the same year Dr. Dre of N.W.A. assaulted a woman, TV host Dee Barnes, at a party in Hollywood. When Barnes, facing homelessness, created a GoFundMe just this past February, the material afterlife of the violence was painfully obvious. Dr. Dre, by contrast, went down in Forbes history as earning more in one year than any living musician when he sold his audio company Beats to Apple for $3 billion in 2014. Two years after the assault, Dr. Dre was on the cover of Tribe’s Midnight Marauders (along with many men, including Ice T, the man now known as P. Diddy, and MC Lyte). “It was a small show of unity, which echoed large as hip-hop’s coasts began to fracture more loudly,” Abdurraqib writes. Unity? Kinship, in fact, must always exclude.

“May we love our brothers, Tip,” Abdurraqib writes in response to Q-Tip’s mourning the death of Phife Dawg in 2016. (“He left me with the gift of unconditional love and brotherhood that will NEVER be lost with me . . . Ever,” Q-Tip wrote of his crewmate.) In both instances, brotherhood is clearly not a gender-neutral term, though some women, like MC Lyte and Queen Latifah, were invited in to the fraternity honorarily. Because the letters in Go Ahead in the Rain’s consist of one man lovingly addressing mostly other men, the book’s epistolary form exaggerates the homosociality that lives in rap’s veins. By way of Queen Latifah and Monie Love, Abdurraqib makes only a rushed nod to the question of black women’s role in hiphop. And yet, in another sense, his whole book is about gender: how people imagine who might be their brothers. (As feminists of all genders sometimes neglect to realize, gender politics does not mean merely the presence of women.) The final paragraph of Go Ahead in the Rain repeats “I hope” five times; it is in this cautiously optimistic sense that, as the book’s jacket reads, A Tribe Called Quest is a “seminal rap group.” They planted seeds, and now we must all reckon with disunity.

Tiana Reid is a writer, editor, and student living in Manhattan.