In “The Cartridge Family,” an old Simpsons episode, there’s a joke about the seeming impossibility of soccer ever becoming popular in the US. We are at an American soccer stadium, and a foreign commentator is off his seat, announcing the match with near-manic enthusiasm. All you see on the field, however, are three players drably passing the ball back and forth at the halfway line. The contrast was meant to evoke the average American’s bewilderment at this “new” sport (of course, many European teams date back to the nineteenth century). But it also touched on a deeper and more widely held presumption: that among all the scruffy tackles, mock injuries, failed attacks, and pointless side-ways passing, not much actually happens during the ninety minutes of a soccer match.

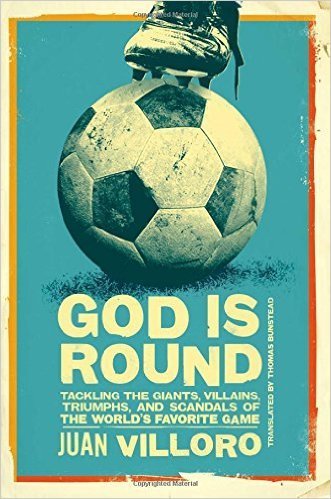

The Mexican writer Juan Villoro offers a very different perspective on this idea in his newly translated collection of essays God Is Round.For him, soccer is a sport that’s always approaching (but never quite reaching) perfection, even when nothing much is happening at all. It is a game in which the action “doesn’t happen, or half-happens, or happens just in the way you don’t want it to happen, but constantly teeters on the edge of coming together just right.”

For Villoro, this sense of constant promise (or constant uncertainty) is soccer’s most important trait—and one that arises from the sport’s unique fluidity.

Soccer is comparable to, say, basketball, in that they are both free-flowing clashes with little temporal structure and constant turnover. But unlike basketball, soccer is a very low scoring affair. This puts a tremendous premium on its every unfolding moment, rendering it at once banal and potentially game-changing. (The opposition team, for example, could spend an entire half encamped near your goalmouth without scoring. But then one long pass from your full back could set your striker off to score a last-minute winner.)

Soccer, in short, is a shapeless sport that constantly threatens to take shape. It’s this constant teetering between potential and actuality, that, according to Villoro, leads fans to infuse a match with their own “superstitions, desires, vengeful wishes, the most tremendous complexes, and legends of enormous intricacy.” And soccer’s pronounced human dimension is what attracts the writer in Villoro to the sport. As he notes in his book’s first major essay: “Stadiums, these theaters of dreams, fill up not only for what happens on the pitch…. Football takes place both on the turf and inside the agitated awareness of the spectators. A sports report is a way of joining these two territories together.”

Villoro has been bridging these territories with much flair for two decades now, though the noun report hardly does justice to his type of writing. More theorist than journalist, he is concerned not simply with the machinations of the sport but also with the forces that shape both players and audience. Think of him as a Barthesian detective: someone equipped to interpret the conflicting passions, emotions, and ideologies that surround every gesture on the field.

God Is Round is not structured around a club’s history, a player’s rise to the top, a famous World Cup victory, or any other overarching narrative. Rather, like Mythologies, it’s a collection of idiosyncratic inquiries: Why, one section ponders, are left-footed players so disproportionately effective? Why do fans remain loyal to their crappy local team? Does thinking get in the way of playing? Are players ever truly devoted to a club? “Sports,” Villoro has said, “represent an articulated form of passion. By looking at sport, we can understand … how we express … our emotions in contemporary society.” He consequently pays close attention to hooliganism, violence, chanting, and other ways that men unleash their repressed sentiments when among the stadium’s crowd (female fans are unfortunately underrepresented in this book).

Villoro is at his best when he devotes an entire essay to a single player, analyzing the soccer star’s play, on-the-field behavior, and psychology. (This makes sense when we consider that he’s first and foremost a writer of literary fiction.) Indeed, the four chapter-length profiles included in God Is Round—which consider Lionel Messi, Diego Maradona, Cristiano Ronaldo, and Ronaldo Luis Nazario de Lima (better known as “Ronaldo”)—provide a far more vivid portrait of their subjects than any authorized biography or documentary I know. Villoro does not base these pieces on interviews—such proximity would cloud his judgment. Instead, he remains at home and imagines his way into his subjects’ lives. The resulting sketches present soccer players not as the professional athletes television commentators make them out to be, but as the flawed, childish, tragicomic demigods fans always suspected they were.

Here Villoro is, for example, explaining the self-destructive urge that drove Maradona, the legendary Argentine striker, into so many calamitous career decisions: “Like Borges’ immortal, Maradona had looked in vain for the river whose waters would confer mortality. The disasters brought him no closer to the common state of his fellow creatures—on the contrary, they showed him how indestructible he was.” His chapter on Real Madrid star Cristiano Ronaldo is similarly barbed with critical acumen and short diatribes. To Villoro, the deplorably self-centered athlete’s self-appointed nickname, CR7,“suggests someone not subject to the normal laws of human nature, a cyborg or an archangel.” Cristano’s on-field behavior is likewise robustly self-aggrandizing:

In Cristiano’s view, soccer is a high performance sport, one in which personal bests come above the ability to enchant. Incapable of identifying with other players, he finds his only reflection in the object of desire: the ball. Cruyff’s legacy was his introduction of the passing game, showing us that the ball ought to be the thing in motion, doing the work. CR7 seeks to reverse this certainty, supplanting the ball as the most looked-at, and most coveted, thing on the pitch.

This sort of armchair analysis could erode the achievements of hard-working athletes, but Villoro’s writing actually has the opposite effect. There’s something numbing about the ludicrously high quality of soccer that’s broadcast on our screens every week. You can forget—as just about everyone does when watching Barcelona’s monotonously beautiful tiki-taka style of play—that forty-five minutes of a top division match contains more moments of grace and brilliance than your beloved pub team manages in an entire season. By imbuing these athletes with complex and sometimes deeply idiosyncratic personalities, Villoro manages to bring some of that magic back into relief—to make it strange and new again. There are countless experts who can rattle off Luis Ronaldo’s career stats, but this won’t capture the player’s haphazard and bizarrely successful style anywhere near as well as Villoro’s description: “When he was bearing down on goal, he was the child chasing after an ice-cream truck: there was no way to hold back either his strength or his desire.” Even his diatribe against CR7 leaves us more (perversely) awestruck by the arch-narcissist’s achievements.

God Is Round also includes essays that engage with soccer in more serious and analytical ways. These, unfortunately, are not very engaging. In “The Sense of Tragedy,” Villoro indulges the psychological pseudo-theory that suffering makes for great footballers: “We know very well from Tolstoy that happy families don’t generate novels. Nor do they produce footballers.” Pursuing the idea, he claims that winners are driven not just by skill but by psychic wounds and discontent.“In group sports, the sense of tragedy needs to be shared by the collective.” According to Villoro, the great Dutch team of 1974 lost the World Cup final to Germany because they were too happy. The Germans, on the other hand, were spurred on by the memory of recent World Cup losses. It’s a touching hypothesis, but one that simply doesn’t hold up. Why, for instance, did Holland proceed to lose another World Cup final four years later? Hadn’t they acquired the requisite suffering by 1978? What about perennial English Premier League also-rans like Arsenal? Surely they could have cashed in on their endless failures by now. This is not addressed.

But God Is Round’s real value lies not in its ideas but in the approach Villoro takes to soccer writing. In his novel Netherlands, Joseph O’Neill describes cricket infielders as “swanning figures on the vast oval [who] again and again converge in unison toward the batsman and again and again scatter back to their starting points, a repetition of pulmonary rhythm as if the field breathed through its luminous visitors.” Measured and painterly in its construction, his sentence somehow transports us (or me, at least) back to a time before adult pressures curtailed our love for the sport. God Is Round achieves something similar for soccer. By marshaling his imagination and linguistic resources, Villoro is able to resuscitate the rich childhood fascination that originally got us praying to the “weekend god.” This is the goal of most expressions of fandom, but only writing as good as Villoro’s can actually accomplish the feat.

Ratik Asokan is a freelance writer based in New York. He writes about literature, film, and photography.