In one of the more bizarre stretches of Mohamedou Ould Slahi’s Guantánamo Diary, the guards who have been presiding over Slahi’s three-year detainment at Gitmo give him the nickname Pillow and inform him that, in turn, they’d like to be called something from the Star Wars movies. The US government has redacted the Star Wars handle his captors wanted Slahi to use when addressing them, but he says it means “the Good Guys.” Perhaps they wanted to be called “the Jedi,” the Zen warrior protagonists in the George Lucas mega-franchise; it’s even more amusing to imagine that they wanted Slahi to call them “the Rebels.” Because this would mean that the guards, in their wisdom and self-awareness, saw Slahi—whom by this point they’ve beaten, frozen, molested, starved, and kept awake for hours on end by blaring the National Anthem—as a hateful member of the Galactic Empire, hellbent on the destruction of the plucky Rebels.

In November of 2001, Slahi, a computer engineer, drove his own car to a meeting with authorities in his native Mauritania. He’d had a glancing association with al-Qaeda in 1992, when he fought the Soviets in Afghanistan (a cause the CIA supported to the tune of $20 billion, in arms and training for the mujahideen), and was used to such questioning. He had moved back to Mauritania from Canada because spooks there tried to tie him to the Millennium Plot, an alleged plan to bomb the Los Angeles airport timed to coincide with the first New Year’s of the twenty-first century. He never drove home from the November meeting. Instead, interrogators took him to Jordan, Afghanistan, and then Cuba, where he was initially considered one of the most valuable detainees at Guantánamo, even though, like so many of the other inmates there, he was never formally accused of anything.

A few reviews have likened Guantánamo Diary to Memoirs from the House of the Dead, written after Dostoyevsky’s four years in Siberian exile. Diary does share that book’s vignette structure. But while Dead‘s narrator draws on his observation of the lives of his fellow prisoners to create a mounting sense of existential despair, the frequently isolated Slahi—who spent a decade in Germany and easily communicates without culture clash—turns his attention to Gitmo’s guards and interrogators. These figures are generalized through redaction and turn out to be, rather than ominous symbols of spiritual dislocation, merely thoughtless and careless—stupidly cruel in ways that only a late-stage empire (or maybe a fraternity) can accommodate.

The guards beat him and tried to convert him to Christianity. They taught him chess and then got angry when he won. “That is not the way I taught you,” one guard scoffed. (Slahi learned his lesson: It really is better to let the Wookiee win.) They threatened to “bring in black people” if he continued refusing to cooperate. “I don’t have any problem with black people, half of my country is black people!” he writes. They asked him to do an interview with “a moderate journalist from The Wall Street Journal and refute the wrong things we’re suspected of.” “Well,” Slahi replied, “I got tortured and I am going to tell the journalist the truth.” The interview was canceled.

A 2004 CIA inspector general report implies that people like Slahi were held in Guantánamo because “if not kept in isolation [they] would likely have divulged information about the circumstances of their detention.” That is to say: They are there because they’ve been there, and should probably never emerge. Security officers treated Slahi as confessor, punching bag, fetish object. They said embarrassing things like “welcome to hell,” “wahrheit macht frei,” and “you are my enemy,” and then watched Gladiator and Black Hawk Down with him. “In America it’s like ‘tell me how many movies you’ve seen, and I’ll tell you who you are,'” Slahi writes, tired.

Slahi became an inadvertent expert on a range of American perversions, like video games (“One of the punishments of their civilization is that Americans are addicted to video games”) and workout magazines (“Is that a homosexual magazine?” he asked a guard poring over one). “Americans worship their bodies,” he observes. “I have a great body,” a female interrogator whispered in his ear. “American men like me to whisper in their ears.” She and another woman later took off their shirts in what, between the redactions, sounds like an outtake from Girls Gone Wild. They rubbed against him and each other, fondling his genitals. “We’re gonna teach you about great American sex,” they hissed.

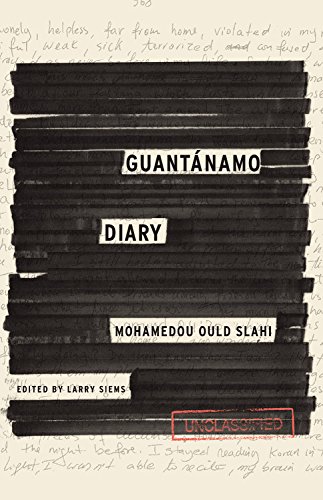

Slahi’s book is not just about a system but was created by it. Its form was determined in part from below—he picked up most of his English from the guards (“I learned that there was no way to speak colloquial English without F—ing this and F—ing that”)—and in part from above, by the black bars of redaction present on almost every page, effectively shellacking another layer of bureaucratic incompetence on a story already overstuffed with it. The bars remove things that matter along with things that don’t: names, nicknames, a poem Slahi writes, even female pronouns (in what might have been a too-little-too-late attempt to placate Muslim readers). The elisions are inconsistent. One interrogator taunted Slahi by bringing “her” lunch into the room, and then is mysteriously rendered genderless in the next sentence: “‘Yummy, ham is tasty,’ [] said eating [] meal.”

The government’s most damning accusation against Slahi is that in 1999 he counseled two men allegedly involved in the 9/11 plot to head to Afghanistan for training, since they wanted to fight Russians as he had, this time in Chechnya. The allegation was based on another detainee’s testimony and little else beyond some chatter investigators picked up in Canada. What did Slahi mean when he said “tea” and “sugar” on the phone that one time, they ask, over the course of two hundred pages.

During his capitivity, he cracked up a little. Someone slipped him a copy of The Catcher in the Rye and he could not stop laughing at it. He tried to collaborate with the US, to confess to everything, but even that wasn’t easy. “You have to make up a complete story that makes sense to the dumbest dummies,” he writes, and bring in people you know to be innocent.

In a moment of frustration near the end of the book, he tries to reason with an interrogator, go through all the hypotheticals that would have had to happen for his own fake confession to be make any sense. He’d have had to ensure that the al-Qaeda recruits made it to Afghanistan and met with al-Qaeda. How was he to know that even one of them would succeed? “What told me that he was ready to be a suicide bomber, and was ready to learn how to fly? This is just ridiculous!”

“But you are very smart,” the interrogator responded.

It’s all too easy to think of Slahi as a mirror, a camera, a literary figure like Aleksandr Petrovich Goryanchikov, Josef K., even Cincinnatus C., a grimly resigned captive who never knows when this will all be over. In that regard, we join him, since we’ve all heard President Obama’s promises to close Gitmo many times before this most recent State of the Union address.

Here’s the worst part: We’re only able to read this book now because of the bureaucratic difficulties involved in publishing it. Slahi actually finished the document in 2005. He’s still in Cuba. One can only imagine what his life is like now.

Dan Duray is a writer living in New York.