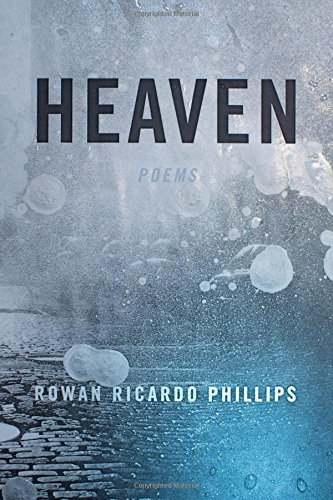

Stars have always provided direction for long-range travelers, whether by land or by sea. Until relatively recently, even modern ships used them to navigate. The stars have inspired entire civilizations, technologies, and literatures; conversely, peoples and cultures have been destroyed by their guidance. How else would Christopher Columbus have reached the Americas? Perhaps appropriately, given its title, Rowan Ricardo Phillips’s second book of poems, Heaven, makes numerous references to the day and night sky: “ . . . that star-beleaguered dome, that void, / Where giants moved against the blinding backdrop.” It imagines that realm as very much real, very near, while simultaneously just out of reach. And since heaven can never be only one thing—at least for Phillips, as opposed to the role it plays for fundamentalists of all sorts—it must be hybrid: both here and there, both you and me, and, most importantly, both paradise and not. Because nothing in Phillips’s book is quite exactly what it seems.

Heaven exists as a series of displacements. Its voice inhabits various languages—English, Greek, Spanish, French, Italian—and locations: Los Angeles, the Colorado Rockies, ancient Troy, Paris, New York City. This elusiveness, this refusal of hardened categories and identities, is a poetics of resistance built into speaking, one that, like creole, blends many tongues. It includes not only different languages, but a poem such as “Never Again Would Birds’ Song Be the Same” (a title borrowed from Robert Frost) that fluidly references both a villanelle’s weave and Ol’ Dirty Bastard. Many of the poems in Heaven function this way with their proportional stanzas, their slipping in and out of conventional prosody, their classical references transfigured into cultural moments both private and shared, just as in his first book of poems, The Ground (2012), Phillips translated a short section of Dante’s Purgatorio to include Bob Marley speaking in Rastafarian dialectic.

In Heaven, each potential landing is also a marooning—a word with its roots in communities of runaway slaves: “my self / Beached at the sea of my soul.” And yet in Heaven everything has the potential to be reversed: “And when he stared out at the sea, / Feeling familiar to himself at last, / He called that Heaven, too.” These frequent references to the ocean and water are partly the sign of diaspora, and specifically the black Atlantic—that geopolitical triangle by which people, commodities (including people as commodities), and cultures circulated between Africa, the newly christened “Americas,” and Europe. It’s the backdrop—the constellation, one might say—for the structural inequalities, whether economic or racial, of the present moment, and Phillips peers to its horizons. Yet he does so in a way that keeps them expanding, never allowing poetry to clamp down, even as he metaphorically strangles Trayvon Martin’s killer, George Zimmerman, wearing “a Hawaiian shirt over a bulletproof vest, / Slumped in a beach chair, its back to the ocean,” or chokes Mel Gibson on his own hate-filled speech.

At the heart of Heaven is “The Beatitudes of Malibu,” an eight-part poem that opens with Phillips as “we” beneath the planet Jupiter before Phillips as “I” begins his carefully constructed yet splintered poem-song: ten lines per section with mostly ten syllables per line and sporadic end rhymes—its relatively fixed form, and its orientation toward Los Angeles, as compass, as GPS. (And perhaps modeled on Wallace Stevens’s “Sunday Morning” and definitely ending with a reference to that poet’s “The Idea of Order at Key West.”) Here is Section VII:

The Pacific encircles me. Slowly.

As though it doesn’t trust me. Or, better

Said, I only understand it this way:

By feeling like a stranger at its blue

Door. The poet with the sea stuck in his

Enjambments can’t call out to some Cathay

As though some Cathay exists and be glad.

No, the differences we have should be felt

And made, through that feeling, an eclipsed lack;

A power to take in what you can’t take back.

Repetition can cut both ways—to delimit or to unfold—and Phillips skillfully uses both to great effect. (It’s not a coincidence that his book of essays from 2010 is titled When Blackness Rhymes with Blackness.) This is language turning against itself—sometimes gently, sometimes sharply—as all poetic language does. Heaven differs and defers as it goes, which is another way of saying that it’s a poetry at home and not at home: “Part of me had / Liked being lost.” If most of the poems in The Ground were set in New York City, much of Heaven originates away from there. The Odyssey—a short section of which Phillips translates for Heaven—might be oriented toward the domestic sphere, but it’s still a poem of exile.

Equally important is Phillips’s emphasis on letting the strange remain strange, letting difference remain difference, because social and political progress entails learning to speak across differences as much as similarities. Thus, he resists the temptation to gaze, as Ezra Pound did, across the Pacific and conjure the Orientalism of an ancient China, idealized as Cathay, whose written characters Pound presumed to understand simply by looking at them. Creolization may be a syncretism, but it’s rooted in disproportionate power relations. And yet even here there’s a qualification in describing differences that can’t be entirely claimed—to “take back”—or perhaps fully known, as a result of their “eclipsed lack.” Poetry is elusive to categories: “The poem that revolves in two directions / At once, circling us in two directions.” Alongside this reference to a dual awareness, a cross-cultural double consciousness, is one in which the poem evades its author’s control.

Nevertheless, Phillips has sprinkled hints regarding his intentions. Upon the release of Heaven, he used social media to share drafts from his notebooks, as well as poems that inspired him, source photographs for imagery, allusions, quotes—what he deems “liner notes”—at #heavenalbumnotes on Facebook and Twitter: John Keats’s “To Autumn,” an image of the guitar pedal referenced in the poem “Boys,” photos of Malibu, etc. They are a fun and useful addendum. If you dig around the Internet a bit more, you’ll find him commenting on his own poems on Genius.com (Phillips takes pleasure in strategically placing hip-hop references amid his poetry’s classicisms) and writing about soccer or art. In other words, he creates a virtual constellation for his work: a little clarification, for sure; a bit of self-promotion, yes; but ultimately providing another layer of meaning to the poetry in a way that makes it more difficult to circumscribe: “Is a poem the wonder or the matter?”

Phillips began The Ground by touching the walls of the Harlem hospital in which he was born; he ends Heaven with a love poem to his partner that signals a settled relationship somewhere around middle age. There’s an allegory of a life being told here across time and place, which isn’t the same as narration. It’s the long range, the long view. If the first heaven is here, the second is her, as in Phillips’s short poem/translation from Dante’s Paradiso: “And, as the swift-shank sinks into its mark / Before the bowstring has time to calm— / So did we speed into the Second Heaven.” Yet Nel mezzo del cammin di nostra vita is how Dante begins his epic. Similarly, in his first two books of poetry, Phillips makes a number of trips to the underworld before arriving beneath the stars, because heaven is always a border. So, too, are poems.

Alan Gilbert is the author of two books of poetry, The Treatment of Monuments (Split Level, 2012) and Late in the Antenna Fields (Futurepoem, 2011), as well as a collection of essays, articles, and reviews entitled Another Future: Poetry and Art in a Postmodern Twilight (Wesleyan, 2006).