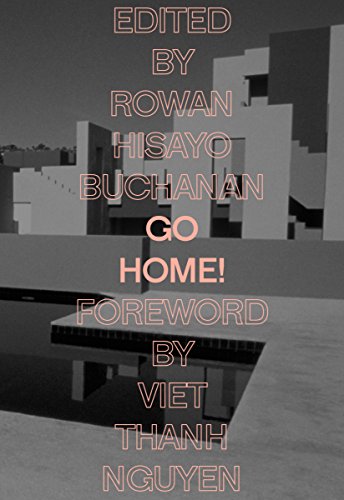

Last month, the Feminist Press at CUNY and the Asian American Writers’ Workshop published Go Home!, an anthology of Asian diasporic writers exploring belonging, identity, family, place, and the myriad other topics that come into play when considering the notion of “home.” We invited the AAWW’s Ken Chen and the Feminist Press’s Jisu Kim to discuss the book with its editor, Rowan Hisayo Buchanan, and contributors Amitava Kumar, Alexander Chee, and Wo Chan. The following is an edited transcript of their conversation.

Ken Chen: Rowan, Can you talk about why you decided to put together this anthology and title it as you did?

Rowan Hisayo Buchanan: Calling the anthology Go Home! felt very natural because home is something I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about. For me, as a mixed-race person, it has always been a slightly elusive place. As a child, I thought home meant a place where everyone looked like you and where you were normal. And such a place always seemed just out of reach. This wasn’t helped by questions like, “What are you?” or “But you don’t look entirely…?”

As I got older, I met others for whom home was a similar preoccupation. Talking to Asian American friends, we’d discuss other ways in which home can be a precarious place due to religion, immigration status, isolation, or estrangement from family. And I was always struck by how these delicate conversations contrasted with that bald “Go Home!” that so many of us have had bawled at us one time or another.

Ken: Jisu, what are things that surprised you in editing this book?

Jisu Kim: I realized that there are very few recent, literary anthologies of Asian writing. That just seemed so odd to me. Many were textbooks, with clear divisions for genre, time period, nationality. For Go Home!, we wanted to avoid re-creating those divisions. I like that our book comes together as a weird mix, because I do think there’s something so nebulous and fictional—but also joyfully messy—about what is called an “Asian American” identity.

Rowan: We had a conversation about whether to specifically label the prose as nonfiction or fiction. We decided not to, I think partially because Asian American and Asian writers are so often asked whether their stories are true, if it’s about their real family, if it’s about them. I wanted to allow for ambiguity.

Ken: I think when someone says “Go home!” or “Go back to where you came from!” and you were born in San Diego or New York or somewhere like that, you are already in the place you came from. But if you’re mixed race then the idea of a homeland is even more strange and impossible. I love the language throughout the anthology, and in the marketing copy and introduction, about home being an impossible place. There’s a way in which home is imaginary, and you were talking about the messiness of writing about home and not having it pre-interpreted for the reader. One thing that struck me is that the book doesn’t feel like an Asian American anthology or an immigrant-writing anthology. What’s clear is that in all the stories home is something the person has imagined and is affective. To start with a very generic question: What does home mean to the four of you writers?

Alexander Chee: Especially if you’re mixed race, the power of self-identification is important—you decide how you belong no matter what someone else might try to adjudicate or legislate. So, when I think about my essay, I think about that experience in particular: At that time in my life, it meant so much to find anyone who looked like me. In this story, finding someone who seemed to be a version of me that I would never be, but that I was interested in, was what I was writing about—how that felt like home.

Wo Chan: I was born in China, but I grew up in a rural part of Virginia. When I think about that place as my factual home I don’t feel that I’m necessarily in my power, or in my full self, when I’m in a space like that. So that’s not the sensation of home or the mythical sensation of home that I like to imagine—a place where I feel safe or strong. Constructing a sense of home is something that a lot of Asian Americans have to do, particularly if you have compounded identities as a queer Asian American. I worked as a makeup artist for a little while and I kind of became obsessed with faces and looked at a lot of faces all the time. So I wrote a couple poems about my own face, and then my mother’s face, as these indicators that we carry into the public. They are literally very surface level, looked at and judged, and oftentimes are the first signs of what other people see as “You’re not at home” or “This isn’t the place you’re supposed to be.”

Amitava Kumar: I felt most at home in just confronting the question: Where is home? The essay I wrote came very quickly, partly because I thought immediately of the “love poems” that I’d written for the border patrol. I always felt that it had been an unequal exchange when I was asked who I was at the visa counter, or when I was insulted at the embassy where I would go back again and again to get the visa. In everything I’ve written I’ve been developing an idea of who I am. Immigration has been a great gift to me because the effort to write about it has made me a writer. In the language that we have developed, and in our struggle with language, we find refuge. It is my search for my identity, and a language suited to it, the achievement of a style or a voice, that makes me a writer.

Jisu: Karissa Chen’s story, “Blue Tears,” does a fantastic job exploring what happens when one’s home undergoes major political change and you’re told to dramatically reconsider what constitutes the homeland. This isn’t merely metaphorical; it’s historical fact. Even if people wanted to comply with the reductive demand to go home, it can be impossible, and geographies and borders change all the time. Nations shift and become other nations.

Ken: It’s like you have a postcolonial Heraclitus—you’ve never stepped in the same country twice.

Amitava: So much of what I think or write about, or even the tension I’m feeling right now on the surface of my skin, is shaped by an awareness of the slur “Go Home.” Even when it has not been uttered, I still feel it. I feel it all the time. And yet what I was thinking this morning was that instead of this always being something I oppose, it is also a part of who I am. The awareness that someone might be saying “go home” to me. I shouldn’t think of my instability or my lack of place, my not feeling at home, as an instigation to go back home. Instead, I should understand that this feeling has been constant for so long that it is also who I am. And maybe the strength of this anthology is the unexpected ways in which people reveal how that feeling, too, is a part of who they are—and then their responses to it. Like the piece by Alice Sola Kim in these pages. It is wild and beautiful. That’s another gift that this book gives us.

Alexander: It took me a long time to realize that the person saying “Go Home” was in fact the person who was alienated and that it was an expression of their alienation, not mine. I have a Korean immigrant father and a white mother from a settler family who has been in the US for over three hundred years. By the standards with which racists yell these things, my claim is at least as valid as theirs.

I spent a lot of time identifying with mutants and with supernatural beings when I was younger. I felt more at home in the uncanny than in any particular place. I had to ask myself at a certain point, How do I belong? What do I belong to? And now it’s a regular question for me. Now I actually have a few places where I feel like I belong. But I did have a very unusual experience last summer. I was in Korea when Trump issued his first “fire and fury” comments, and people were thinking that nuclear war was going to happen that day. I was confronted with the possibility of dying there. I was really at peace in a way that surprised me. I guess the answers for me are complicated and there’s no one single place.

Ken: One theme of the book, and in a lot of Asian American writing, is rebellion from your family, and home is congruent with your family. There’s your linkage with the mythical homeland if you’re second generation. And the act of announcing “I am a self” and “I am an independent person” is usually, like, being a snotty brat to your parents. But in the case of an immigrant family it’s much more complex because your parent connects you to your putative authenticity, so by denying them, there’s another subtext. Amitava, I know you have an essay where you talk about when you landed in America—you immediately started eating beef as a rebellious gesture. Rowan, your story is an allegory and part of it is about the possibility of transformation. Home is not passive, it’s not where you came from, but it’s active. It’s what you have created.

Amitava: There’s a memory I have of the Asian American Writers’ Workshop, where there were some young people who were selling samosas with a sign that said: “Fight Racism, Buy Samosas.” I don’t think the youth necessarily thought that racism was going to be dismantled this way, but they were playing with what you might call “putative authenticity.” They were attributing a quality to something that they like, a samosa, and making it a part of this other landscape. They were bringing those worlds together in new inventive ways and saying something rebellious. That’s how I saw my own writing at that time and perhaps still do. So that’s it then: creating joy. Manufacturing frisson in the response to the political landscape. I think we have to say something very quickly that the call for this volume came after Trump was elected. I don’t know if it was planned that way, but that’s how I have narrativized it. That, in other words, my own eager response to the call was a part of my thinking about what we had to do under the new administration.

Jisu: We began talking about this anthology in 2015. But even though Rowan and Jyothi Natarajan [from the Asian American Writers’ Workshop] and I were talking about the book very early on, many of the pieces didn’t come in until after Trump was elected. Or they came in during the presidential campaign, when immigration and race-related issues were actively being discussed in mainstream media. People responded during this new political context, when it was impossible not to think about these things because they were in full force once again.

Ken: The anthology is about immigration, but no one is really saying, “This is my identity. You should consume it from the outside so you know what it’s like to be an immigrant, to be queer, to be a woman, or to be Asian American.” A lot of the ways we consume race are about scandal or calling someone out or presenting a kind of racial authenticity to the mainstream. What was great about the anthology is it’s people saying things that they had to say themselves, in ways that might be marked or unmarked.

Wo: I guess what’s written on paper is very different than what’s written on your face. And when I say “paper” I mean your documentation. What’s marked down legally is always something that I think about when I think about where home is. For both myself and my parents, we’ve been separately going through journeys of homemaking. With my parents, I can obviously trace the countries that they’ve gone through, the journey that they’ve taken to create a home for us in the States. For myself it’s a little more of a nebulous process where, as a young person, I dressed parts of my identities that my parents can’t understand or things that I’m interested in that I can’t really communicate to them. As I’m getting more perspective on it I’m beginning to respect that my parents are also in the process of homemaking and housekeeping. Keeping the home that they’ve made.

Ken: Alex, I wonder how you’re thinking about your own writing in this context.

Alexander: I’m working with all of these Asian American college students here at Dartmouth. One of them wrote something that I’ve been thinking about a lot recently, where she described what she called Asian American culture in her hometown of Temple City, which is a multi-Asian-American cultural synthesis. These kids who are from different Asian backgrounds but are hanging out with each other—that’s where she feels like she belongs more than the culture that her parents come from. In some ways, that’s what this anthology is also doing culturally. It’s a part of what the Asian American Writers’ Workshop does. I was thinking about this in relationship to the idea of authenticity that you might or might not get from your parents. A lot of what I see us doing, whether we know it or not, is reaching for what authenticity might mean for us specifically, how we create it for ourselves, how we are authentic to ourselves and each other. I won’t say that I’m not responding to the Trump administration—my social media is basically directed at responding to that as much as I can stand it. But my writing can’t just be aimed at him.

After the election, most of the writers I knew felt like they were operating inside of a different context. Many of them who were publishing books changed those books as a way of thinking about that new context. They felt that the world they thought they were going to live in had died and that they were in this other world. I find myself at age fifty feeling utterly bitter about how much of my life has been spent resisting the thirty-plus-year right-wing takeover of this country. I know I’ll never get all that time back, and so my writing always has to come from some other place.

Rowan: I often don’t consciously think about the Trump administration when I’m writing because that would make me too miserable to write. Instead I think about my family.

When I was a kid trying to find out about people like me I searched for “mixed-race” on the internet. The result that came up again and again was the Stormfront website. In the Stormfront forums, there is serious discussion about where mixed-race people could be deported. Stormfront users claim that mixed-race people are “against nature.” Recently, Stormfront has been on the news because it’s a hotbed of alt-right and Trump supporters. Every time I see the name I wince.

So writing stories about multiracial families and saying it’s important to have stories about them is my very small rebellion.

Jisu: One of my greatest hopes for Go Home! is that it can be a chance for folks who identify as, or are identified as, Asian American to talk to each other within this grouping, and also across differences in nationality and other identities. I’m a one-point-five-generation immigrant who grew up in an insular Korean immigrant community, and we didn’t think of ourselves as being part of a shared community with other Asian immigrants in the area. My parents and the church elders I grew up with thought of ourselves as very separate from other minority groups in the US. It was very much “us against them,” like we couldn’t both win. And each time I saw minority representation in literature, it depicted ethnic minorities only in conversation with whiteness anyway: How is a young Korean American going to fit in with her white classmates? It was never: What would a friendship look like between a Korean American girl and her Vietnamese American classmate, and what kinds of struggles and joys might they have? The experience of an ethnic minority was always mediated through whiteness. I’m interested in writing that explores minorities speaking to each other, even when it’s not pretty. I think it makes us really uncomfortable to think about minority communities turning against each other, or turning against folks within their own supposed communities. But that kind of literature is important if we are to think about people’s lives in a holistic and diverse and realistic way. I’ve resolidified my commitment to these conversations because the Trump administration is so performative, and it’s easy to forget about less obvious divisions in the face of overt white nationalism. But it’s absolutely necessary to keep pushing at these questions: As an Asian American community, how are we responding to issues of police brutality, incarceration, or the refugee crisis? Who are we excluding when we push for Asian American representation? And so on.

Ken: One problem with thinking about Trump is thinking that he’s an exception to this country’s overall politics when, in a lot of ways, he’s a standard Republican. It’s important to have anti-racism but it’s also important to have racial justice. It’s important to resist but it’s also important to create the kind of society that feels more free and liberated and egalitarian. Go Home!, the work that all of you do as writers, and the work of the Feminist Press and the Asian American Writers’ Workshop, is a rehearsal for a place that might be more equal.

A few final questions: Is there any advice you would give to your younger self or to your student or your child? What would you say to help them navigate these issues, to feel more at home in the world as a reader and writer?

Amitava: Someone like Ta-Nehisi Coates is doing a better job than I can of addressing the challenges of this administration. I try to do something different. Let me get to that point with a story. Yesterday I was teaching The Lover by Marguerite Duras. I was shocked that my students didn’t like the book. They didn’t like it because as a couple of them said it’s about child rape. And yes, I was impressed that they had properly understood what’s going on with the #MeToo campaign, and they understood what a figure like Roy Moore means. But I also thought that in their response there was such a narrowing of an affective literary consciousness. I was disappointed that they were not alert to everything that Duras was doing. I would like to say to my younger self that, yes, look at the books around the shelves of the Asian American Writers’ Workshop if they give you tools for understanding resistance or of defining a resistant self, but don’t reduce your life to a fucking slogan. Because one of the amazing things about life is how wide-ranging and complex it is. We cannot let our humanity, or the fullness of our emotions, be defined solely by the experience of oppression. One of the strengths of Go Home! is the breadth of affective registers in which these authors function.

Alexander: I think there’s an idea of being a writer that we’re sold in which there’s a lot of talk about solitude and not as much talk about community. And communities of writers are part of how I have achieved everything that I have for myself as a writer. I want to make sure that whoever’s coming in knows that conversations and communities are a big part of this. It’s not just about showing up for a reading even though that can be life changing. When I was starting out, I don’t think I realized how many people I was starting out with would keep going but also how many of them might not. And I’m thinking of a conversation I had with Ocean Vuong, who I was interviewing for a magazine, where he told me that he thought of me as a survivor. Essentially, that all of the writers he saw as elders, he thought of as survivors. And that was interesting because I had not figured myself that way and I understand my career differently in light of that. I look around now for who’s not with me and I go looking for them and find out what happened to them, what happened to the stories they were trying to tell. Same with my students and same with my elders.

Wo: The most solid piece I could give to other folks, or to myself, is just to show up in as many ways as you can. And that changes a lot depending on where you are and what access you have—for a lot of folks that’s having a strong internet presence. I’m really grateful that I was able, even five years ago, to go to so many of my friends’ readings and participate in so many workshops and give my own readings. When I had obligations to give a show or a reading, and I wasn’t feeling my best, I would go kind of grudgingly. But I never thought about the fact that for some of the folks in the audience what I was providing on stage was their sense of home. You can see in their eyes that you had given them something—even if you’re feeling like crap and you’re sick. So, show up for other people. Because you never know who you’re actually showing up for.

Rowan: My advice to past me is that it’s OK to have a fluid identity. After my novel came out, interviewers asked me what the most important part of my identity was. Was I more Japanese, Chinese, British, or American? But I think it’s OK not to know which one is most important, or to have one be more important one day and less the next. It’s OK to have days when you’re thinking really hard about your identity and fighting for it. And it’s OK not to think about it sometimes. It’s OK to be thinking about ethnic identity one day, mental health the next, and your cactus the day after.

In the age when every person is declaring themselves constantly to be something, there is a pressure to say, “This is who I am,” and then stick with it and make a platform of it. But it’s OK to shift and change and be excited by that.

My second piece of advice to my past self is to remember that others are struggling with their own identities. Sometimes, this struggle will be invisible. People who seem totally at home, often aren’t. Listen carefully.