It’s tempting to imagine Bette Howland as a figure of midcentury literary mythology. Who can resist the intrigue of her early crisis and success, quiet disappearance, and belated rediscovery? She is, as Honor Moore remarks drily in the afterword to Howland’s posthumous story collection, Calm Sea and Prosperous Voyage, “a member of a cohort who have benefited from the forty-year gap between the end of a woman’s youth and beauty when, at say forty, one’s reputation goes dark, until eighty or so, when one becomes a discovery.” The pitch for a prestige television biopic practically writes itself. I imagine it illustrated with the impossibly winsome photographs that have surfaced of Howland, demurely sunbathing in a periwinkle one-piece and cat-eye shades, or wearing a coy smirk and a jaunty fedora, looking like Anna Karina in an early Godard film.

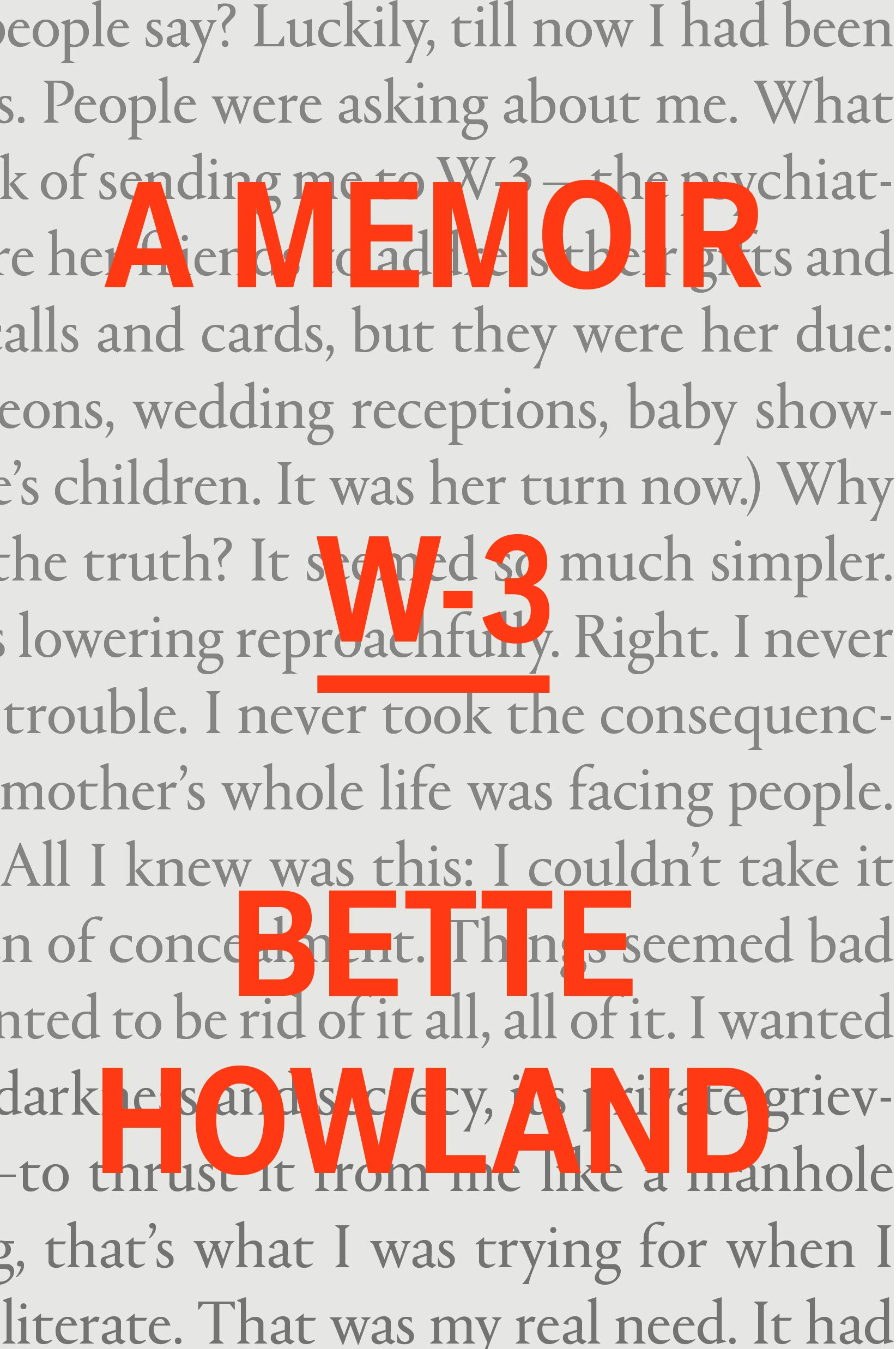

The public events of Howland’s life are tantalizingly dramatic. She was born to a working-class family in 1937, and enrolled at the University of Chicago at fifteen. By the age of thirty, she had married, given birth to two sons, divorced, held various jobs, and met Saul Bellow, her sometime lover and a longtime supporter of her work. In 1968, she survived a near-successful suicide attempt and was hospitalized in a psychiatric ward, the experience described in her short memoir, W-3, first published in 1974. Howland’s voice in this debut is irresistibly raw, wry, and brilliantly economical. Howland went on to publish two short story collections, took prestigious residencies at Yaddo and MacDowell, won a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1978, and a MacArthur grant in 1984. After receiving her genius grant, Howland never published another book. By the time Brigid Hughes, the founding editor of the magazine A Public Space, stumbled upon a used copy of W-3 in a bargain bin in 2015, Howland was near the end of her long life, suffering from dementia and multiple sclerosis, her books all out of print. She died in 2017. She didn’t witness the glowing reception that greeted Calm Sea and Prosperous Voyage when it was published by A Public Space Books in 2019, or see W-3 reissued this January.

Based on the cinematic allure of this tale, a reader might imagine—or perhaps hope—that W-3 would focus on the brilliant, mysterious woman at its center. It is, after all, the memoir of a writer’s breakdown, a genre that ostensibly grants privileged, direct access, whether real or illusory, to the most intimate anxieties and vulnerabilities of its authors. But one of the most compelling aspects of Howland’s memoir is instead the peripheral presence of Howland herself. After the title page, her name appears only once, very near the end. Her dear friend’s aunt, whom she has never met, comes to the ward to visit; approaching the narrator we know only as “I” in the hall, the visitor asks “if I knew anyone by the name of Bette Howland.” We do not hear her response. Seeing the name of the author is momentarily jarring: while fragments of the narrator’s personal story emerge throughout the book, it’s possible at times to forget that it is a memoir. The account of Howland’s conversation with her friend’s aunt turns quickly to a vivid sketch of the visitor’s life on Chicago’s South Side. The “I” deftly sidesteps “Bette Howland” here, offering instead a striking, concise portrait of a woman she has just met.

This anecdote is a pocket version of the broader strategy of W-3. The narrator is a keen and constant observer of everyone she encounters, and particularly of the loose net of tenuous but sometimes tender relationships between fellow patients, nurses, doctors, and rare visitors. The title gestures immediately to the spread of this memoir’s scope, from the individual subject to the shared space: W-3 is the name of the ward, a place that was there before Howland arrived, and remains after her departure. Once Howland moves to W-3, after a very brief, impressionistic account of her time in the ICU, the narrator moves from singular to plural. The unremarked shift from the language of “I” and “me” to that of “we” and “us” signals her entry into a world in which the individual self, declared unfit or incapable of belonging to the population outside, belongs to a kind of uneasy but necessary group inside. At first, this integration is alarming: “On W-3 you encountered the terrible force of a generalization, and it had to be resisted, the self had to be exerted. Anything to deny this grim, inert, collective state.” Yet more often than not the active “exertion” of the self is futile: the ward “wasn’t a good place to practice individuality, self-expression. You might end up expressing someone else.” Everyone is uniquely, yet uniformly, unpredictable.

This is certainly not to say that all of the patients are the same; far from it. Most of W-3 is a gallery of marvelously, devastatingly precise miniatures of Howland’s fellow inmates. Howland’s eye for detail is unfailingly sharp. She has the cartoonist’s knack of seizing and drawing out a person’s specific mannerisms and fixations, but what results is never caricature; rather, her depiction of the patients of W-3 is sensitive and sympathetic but powerfully unsentimental. This approach is best demonstrated in a remarkable scene near the book’s end, where the patients play a game that seems like a clear invitation to disaster: they draw each other’s names from a hat and exchange identities. The potential for cruelty is unbearable. Yet the resulting theatrics manage, like Howland’s prose, to depict the idiosyncrasies of each patient with an honesty so plain and intimate it can be nothing but tender. The same can be said of her rare descriptions of her own condition. These clear-eyed portraits are all jarringly exceptional on their own, but seen together, create an oddly harmonious and cohesive image. “There was no novelty,” writes Howland. “One gesture was stale, powerless, and unoriginal as the next. Nothing was original on W-3. That was its truth and beauty.”

This setting is at once highly specific and highly interchangeable. As Yiyun Li writes in her new introduction to the book, drawing on her own experience of hospitalization: “Temporal and geographical settings matter little in the eternal struggle between lucidity and lunacy. The characters in W-3 could be the same people I encountered in S-6, the ward where I stayed.” I could say the same about HCC-10, the ward where I was admitted after my own breakdown. Far better than many other memoirs of mental illness, Howland’s precise account captures how the psychiatric ward is more like a different plane of existence than a single place, whose inhabitants live in an unpredictable fellowship that is at once community and its opposite. Observing a clique of recovering addicts from the narcotic ward next door, Howland notes how

they stuck together; they were truly a body, a group, in the sense that we on W-3 could never be. And maybe the “clothes,” the “community,” all the social emphasis of W-3 was really meant to prevent this from happening—precisely this; to prevent us from ganging up, closing ranks in the instinctive, elementary way: we against them.

Of course this was never totally preventable. Only on W-3 it took the form of discovery—which came for all of us sooner or later—that we were they.

Having been part of the “we” that Howland describes—an unsteady but strongly felt collective that cuts unpredictably across race, gender, diagnosis, and class—I find myself curious about those to whom “we” might also be “they.” There is, at times, an almost pedagogical quality to the way Howland speaks both to and as a hypothetical “you.” Sometimes these comments are matter-of-fact accounts (“You don’t get much notice for a trip to a place like W-3”). At others, they are more confrontational: “The gist of all the pep talks is that you can help yourself; you can straighten up, buckle down, fly right. But what if there comes a moment when you can’t?”

By the end of the book, Howland’s constant roving between “I,” “you,” “we,” and “they” seems like a part of the long process of leaving W-3 without abandoning the past. Ultimately, she departs W-3 feeling “free of my own personality, my particular history. Not so private, particular, and personal after all. Now I was ready to reclaim it—though it could never be of as much interest to me again.” It’s too easy to say that the freedom Howland writes of here is a simple release of the burden of her personal struggle. Rather, it is an unusual liberation of perspective: having been more than just “I,” it seems that she is able to look at her “particular history” from the shared distance of “we,” or even “they.”

When I first read about Howland’s life and career, I was surprised to find that she lived so long, relieved that she had not ultimately committed suicide. W-3 ends abruptly, without the kind of moral wisdom or poignant aphorism that often concludes a memoir. This, to me, is exactly enough. I don’t need or want to get mired in the fascinations of the “private, particular, and personal” events after Howland’s discharge from W-3. It is enough to simply know that they occurred.

Sarah Chihaya is an assistant professor of English at Princeton University, and an author of The Ferrante Letters: An Experiment in Collective Criticism (Columbia University Press, 2020).