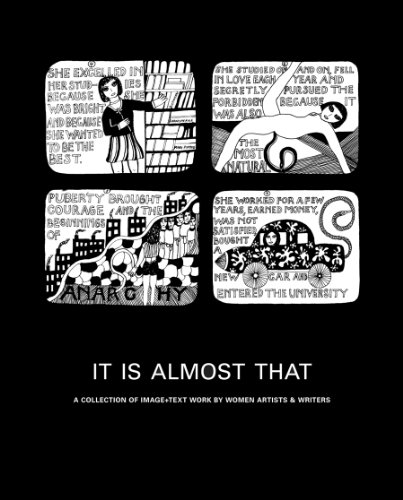

The title of this surprising collection of image/text works by twenty-five female visual artists and writers is a phrase borrowed from a 1977 artwork by Theresa Hak Kyung Cha. As Lisa Pearson writes in her afterword, It Is Almost That describes “the humming state of the not-quite this and not quite that,” namely, “what familiar taxonomies cannot order.” Hak Kyung Cha’s piece—composed of faltering phrases projected on black-and-white slides—points to the provisional nature of language and speech. While Pearson’s penchant for this open, indeterminate state might seem at first to evoke categories like ecriture feminine, twentieth-century Language-school poetry, or non-diegetic experimental filmmaking, her selections, works produced over a span of seventy-one years from Charlotte Salomon’s 1940 visual novel Life? Or Theater? A Song Play to Bhanu & Rohini Kapil’s 2011 India Notebooks, defy easy classification.

Explaining her decision to select only from works composed by women, Pearson asserts: “There is still deep gender inequality when it comes to the coveted real estate of exhibitions . . . and I preferred to make space . . . for work by women.” Her statement seems as dangerously uncool as it is accurate, but Pearson’s boldest editorial move is bringing together works by artists and writers who are not normally thought of together. Pearson’s genre-defying conflation of formalist language-based work with pieces by confrontationists such as Adrian Piper, Carrie Mae Weems, and Sue Williams suggests new affinities. Pearson’s writers and artists use disparate means to probe experience from the outside. While pieces by artists like Hak Kyung Cha and Alison Knowles use text to examine the nature of meaning, perception, and language, others like Adrian Piper’s Political Portraits and Carrie Mae Weem’s haunting Sea Island Series, use words as polemic. Still others pursue a poetics of the quotidian, using pictures and words to describe particular places and states of being. For example, the Kapils’ stunning chronicle of a trip to New Delhi excerpted from their Nightboat book Schizophrene concludes: “Looking down, I saw the red rooftops of the East End stretch out in a crenellate, and then I went home. I documented the corridor and then I went home. What kind of person goes home?” Some of the pieces—most notably, Louise Bourgeois’s rarely-seen 1947 artist book He Disappeared into Complete Silence, in which drawings of unrealized sculptures are set against disjointed mock-journal entries written in imperfect English, and Unica Zurn’s 1958 artist book The House of Illness—are deeply disturbing. Others, like Eleanor Antin’s 1971 “Domestic Peace,” a group of faux social science graphs of “safe” conversational topics with the artist’s mother, are laugh-out-loud funny. The dissonance between the work’s high-conceptual frame and the chronicle of petty domestic bickering it contains is part of the humor: Richard Kostelanetz meets Joan Rivers.

Most welcome of all is Pearson’s inclusion of Bernadette Mayer’s 1971 photo/text project Memory and an excerpt from the late Hannah Weiner’s 1972 Pictures and Early Words. Ripe for recontextualization, the early work of both poets sprang partly from their involvement with New York conceptual art during those years. In subsequent decades, these writings came to be read (if at all) within the Language School canon, the radical epistemologies devised by these writers eclipsed by their linguistic strategies.

In Memory, Mayer, then twenty-six years old, undertook to record thirty days of her life through a series of more than one-thousand snapshots and a taped narration that, when transcribed, filled nearly two-hundred pages. Spiraling, grandiose, and raw, Memory is a gorgeous attempt to affix mental and physical drift into pattern. Close in intent to the work of Mayer’s friend and sometime collaborator Vito Acconci, the grand scope of Memory wasn’t fully perceived when Mayer first exhibited it. Commenting on the project one year later in her subsequent work, Studying Hunger, Mayer wrote: “MEMORY was described by A. D. Coleman as ‘an enormous accumulation of data.’ I had described it as an ‘emotional science project.’ I was right.” In Pictures and Early Words, Weiner famously began to record her clairvoyant-schizophrenic experiences, transcribing the words that began to appear before her eyes in capital letters, slants, and italics. Free of self-interpretation, Weiner’s remarkable writings, which she later developed as “clair-style” poems, describe an out-of-body experience in the most prosaic terms: “It’s true I’m not hungry. Water suffices. . . . I’ve had it with the lights. My eyes hurt. NOT MY EYES on chair. What else? No answer.”

Designed by Natalie Kraft, It Is Almost That is entirely produced in shades of sumptuous gray—“infinite shadows . . . the in-between like twilight and shadows,” as Pearson describes it. A labor of love, the book is also an important step towards the amplification of “minor,” uneasily categorized experience.

Chris Kraus is a critic, novelist, filmmaker, and professor. Her most recent book is Where Art Belongs (Semiotext(e), 2011).