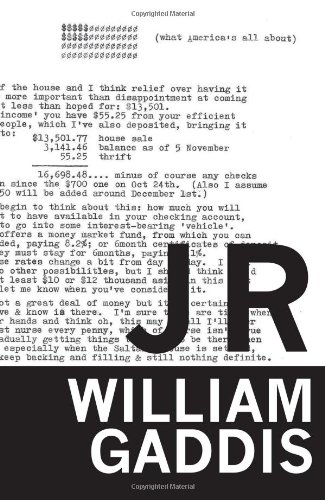

The Recognitions, William Gaddis’s first novel, spent the two decades after its 1955 publication as an often out-of-print cult novel, read and discussed by a cadre of devotees who, as William Gass writes in his introduction to the 1993 Penguin Classics edition, “would keep its existence known until such time as it could be accepted as a classic.” For Gaddis fanatics, this history has become a kind of fable: how the great author, driven underground by critical ignorance and the neglect of his publisher, worked various corporate jobs until, in 1975, he would return to lampoon Wall Street in his massive black-comic novel J R. Thanks in part to Gass and Mary McCarthy, J R won the National Book Award and brought Gaddis a level of recognition not previously granted him. In recent years, Penguin has allowed both The Recognitions and J R to lapse from print—not again!—but Dalkey Archive Press has, thankfully, reissued both books in handsome new editions, with Rick Moody enlisted to write a new introduction to J R. It’s cause for celebration, even if Moody’s opening blast, enthusiastic but short on analysis, isn’t as insightful as the more scholarly preface that the late, great NYU English professor Frederick R. Karl wrote for the 1993 Penguin Classics release.

J R follows the rise and fall of JR Vansant, an eleven-year-old sixth-grader in Long Island who builds a massive financial operation by telephone. Gaddis assembles an enormous cast of characters around JR, all of whose lives come to intersect in some way with the sixth-grader’s paper empire. There’s his teacher Amy Joubert, who unwittingly introduces JR to the power of finance when she takes her students on a field trip to Wall Street, where her uncle runs the powerful Diamond Cable corporation. There’s Jack Gibbs, the manic, drunken physics teacher, in love with Amy and his own thwarted ambition. There’s Edward Bast, an aspiring composer hired with an arts-foundation grant to teach at JR’s school, where, hilariously, he is expected to direct a sixth-grade production of Das Rheingold (JR, of course, in the role of Alberich). Naïve and easily bullied, Bast finds himself coerced into acting as the JR Corp.’s public face, and throughout the novel he remains the only character aware that the new corporate mastermind is just a kid. The book’s comic invention is huge, complete with such vivid secondary characters as Crawley, a hunting-obsessed stockbroker who commissions Bast to write “zebra music” for the soundtrack to a film lobbying Congress to transport African big game to US national parklands, or Mr. Whiteback, the middle school principal who also runs the local bank from his office. Gaddis excels at serious farce, like Nathanael West on a massive canvas.

If people know anything about J R, they tend to know that it consists almost entirely of unattributed dialogue. The novel’s reputation for difficulty is overstated but not without cause: J R teaches the reader how to read it, and some tolerance for confusion is necessary. One learns to identify characters through the verbal leitmotifs that appear in their speech with tic-like regularity. Often, we only hear one side of a telephone conversation. Sometimes we don’t know who’s talking, or we can’t understand what’s being said—whole swaths of conversation are constructed out of the technical jargons of finance and the law. Here’s a representative passage, barked into the phone by Amy’s uncle from a hospital bed, where he’s being prepped for surgery:

Beaton still digging up the figures on it sounds like the kind of stunt they tried to pull at the last minute there loading their Ray-X payroll with everybody in this damn fool family of companies right down to the scrubwomen build up their overhead on these cost-plus contracts looked like they had half the damn country working on them, they… Know that damn it so’s the damn bank, can’t expect us to keep nursing it can you? Thought maybe Typhon could take it on Beaton tells me we’d run straight into antitrust only other damn thing’s DOD, already tied up in these cost overruns and… Well by God whose damn fault’s that! DOD’s projects aren’t they? DOD contracts aren’t they? So damn tied up in it cost overruns all the rest let them take over the whole shooting match can’t expect the stockholders to… No dividend nonvoting nonconvertible company redeems it in five years from after-tax prof…well why the devil’d you think I told you to hold up this damn vote, arms procurement budget this size you can damn well squeeze in this many million nobody look at it twice.

Such passages evoke the world of finance without rendering it any clearer to the layman. The literary critic Roland Barthes famously wrote of the modern novel’s dependence on apparently superfluous details to generate a “reality effect,” a texture of verisimilitude within which a literary plot can appear realistic. The classic versions of this effect depend on the anchoring function of small details; in their functional irrelevance, such details confirm that the world in which the story takes place is, or is like, the real world. J R’s financial discourses enact a kind of reality effect, but the pages and pages of jargon reverse the order of priority between story and detail. For here, the detailed reality crowds out the plot. The result is curious, even paradoxical: the insane energy with which these passages unfurl induces an oddly invigorated boredom.

The counterpoint to the world of high finance in J R is the world of the struggling artist, here represented by Bast, Gibbs, and their friend Eigen, a Gaddis-figure who “wrote a very important book once.” After the suicide of their mutual friend Schramm, Eigen and Gibbs, accompanied by Bast, convene in the epically messy 96th Street apartment where Schramm had been staying and where he died. They are joined by Rhoda, Schramm’s ex-girlfriend, a strung-out, coke-snorting hippie who manages to keep everyone fed through periodic shoplifting excursions. Gibbs hopes to return to the manuscript he’s been working on for years, an ambitious treatise on the history of mechanization and the arts. Bast hopes to compose. The cartoonishly escalating disorder of the apartment renders such ambitions hopeless, especially since JR, through Bast, has been using the address as JR Corp.’s headquarters. Between the perpetual business-related phone calls, the ceaseless deliveries (JR specializes in buying and reselling cheap surplus goods, but, inconveniently, he has to use the 96th Street apartment as a warehouse), not to mention Gibbs’s furious drinking, very little work gets done. The characters run around like spastic starving artists in some imaginary Charlie Chaplin film about the exigencies of creative life. It’s not all funny, though: Gibbs, especially, strikes the genuine tragic note, and in his rage and flailing disappointment he expresses a bohemian puritanism very much like Gaddis’s own. The pain of Gibbs’s failure is one of J R’s chief poignancies.

JR himself, for all his greed, is an oddly affecting little devil, evidently neglected at home and more or less ignored by his peers. His acquisitiveness is amoral, not evil, though he resists every grown-up’s attempt to acquaint him with an ethical code or to get him to think about the consequences of his behavior. He does this, tellingly, by invoking corporate norms. JR’s defense, which he trots out whenever Bast suggests that he might be doing something wrong, is “But what am I supposed to do?” He reiterates versions of this line dozens of times, in aggressive self-vindication. “I didn’t invent it I mean this is what you do!” “I have this here investment I have to protect it don’t I?” JR’s aggrieved refrain resonates rather nicely with the petulant defensiveness of our own financial elites. And like them, JR has no feel for the consequences of his greed, consequences that, not to reveal too much, range from evaporated pension funds to massacres abroad. The voice Gaddis has created for JR—a snot-nosed whine consisting of one part semi-digested financial jargon, one part slightly a-grammatical childspeak—gives rise to some of the novel’s funniest and most distressing dialogue.

Not all of J R is dialogue, though. The novel contains passages of descriptive prose unmatched in postwar American fiction. Gaddis had a fine eye for the pastoral, and the lovely descriptions of suburban Long Island—like those of the northern Hudson Valley in Carpenter’s Gothic—provide a kind of charged relief from the maddening welter of voices. But the relief is not a retreat. The speed is still there, and the breathless rhythm. Moments of natural beauty are:

mere punctuations in this aimless spread of evening past the firehouse and the crumbling Marine Memorial, the blooded barberry and woodbine’s silent siege and the desirable property For Sale, up weeded ruts and Queen Anne’s laces to finally mount the sky itself where another blue day brought even more the shock of fall in its brilliance, spread loss like shipwreck on high winds tossing those oaks back in waves blown over with whitecaps where their leaves showed light undersides and dead branches cast brown sprays to the surface…

These passages hinge on a lyricism both accelerated and clotted, afraid of its own satisfactions, rushing onward to assorted harder realities: money, corruption, the law. The autumnal New York State landscape is ever retreating on the horizon, drowned out by a flood of voices.

The finance guys are obviously villains, and the artists hopelessly impractical, preening, narcissistic. Does anyone in J R articulate a viable critique? Perhaps not, but the apparently hapless Rhoda does give us something like the book’s thesis. Rhoda—sloppy, unkempt, joylessly sexual, uneducated—is the novel’s only emblem of the counterculture, and the characterization is not, on the surface, very kind. Unlike Pynchon, whose novels vibrate in sympathy with the rebellious energies of the ’60s and ’70s, the temperamentally conservative Gaddis saw youth culture as another symptom of generalized disorder. Rhoda proves more, though, than some mean-spirited caricature of “kids today”; her devastating rebukes to Eigen, Gibbs, and Bast—she sees through all their bluffs—allow Gaddis to criticize the very characters whose blasted, romantic idealism he finds himself most attached to. Nor does Gaddis merely dismiss the radical potential of the counterculture, and Rhoda’s semi-articulate defense of revolutionary political anger reverberates across J R: “Like I mean you forget how you know? I mean like hating all these wise-ass generals and fucked up presidents we get and like these banks and faceless reverend garbage peels and asshole politicians I mean it’s just this big drag and like you forget, you know? I mean like really how to hate?” If Gaddis remains less read than his formal achievements warrant, it is surely in part because of the committed seriousness with which his fictions insist on reminding us how to hate.

J R is a novel not just of the ’70s but of our own blighted moment. Its rage against corporate venality, pointless military adventures, incompetence in high places, and the oligarchical grip of what we’ve come to call “the one percent” could not be better tailored to the present. Here’s JR explaining how to avoid paying taxes on corporate profit: “I mean if you’d read up these here booklets where I find out all this stuff see if you go right and sell it you get taxed like this salary where you’re some dumb teacher or bus driver or something you know?” Gaddis nailed it, right down to the contempt of the rich towards people who work. Should the Occupy Wall Street movement find itself in need of a difficult postmodern mega-novel,

J R is the obvious choice.

Len Gutkin is a PhD Candidate in the English Department at Yale. He has written about books for MAKE, The Brooklyn Rail, and Rain Taxi.