Joe Sacco is Art Spiegelman with a passport, or Jon Lee Anderson with a sketchpad. Sacco’s “comics journalism”—intensively researched and reported stories told through text and illustrations—are deeply humane, disturbing portraits of war, oppression, and sectarian tension. Since turning his attention abroad in the late ’80s, Sacco has produced articles and books about the Middle East, South Asia, and elsewhere that rival the reporting of most top-flight foreign correspondents. His work, moreover, is a reminder of the hidebound nature of much international reporting, and of the potential for creative disruption in the field. If there were any justice in American media, a hundred Saccos would bloom.

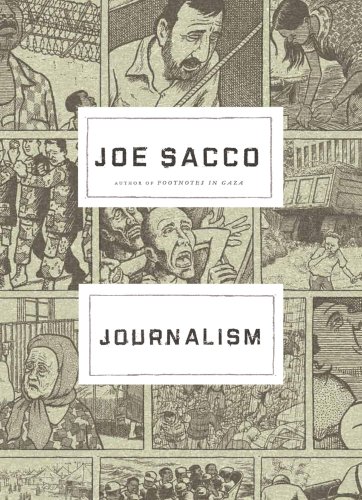

Sacco’s latest book, a miscellany with the modest (or self-satisfied, depending on your interpretation) title of Journalism, gathers his reports from war crimes tribunals at the Hague, the Palestinian territories, the Caucasus, Iraq, Malta, and India over the past ten years. Journalism comes at the same time as Sacco’s Days of Destruction, Days of Revolt, a collaboration with journalist Chris Hedges that chronicles America’s so-called “sacrifice zones”—places of exploitation and poverty that include mining communities, Native American lands, and, symbolically, Zuccotti Park. Of the two volumes the stories in Journalism may offer a better introduction to Sacco’s work, though it lacks the sustained intensity of his book-length narratives.

The finest section in Journalism is “The Caucasus,” which includes the searing story, “Chechen War, Chechen Women,” based on interviews with women struggling to survive in refugee camps across Chechnya and Ingushetia. Though Russia is nominally responsible for these camps, the rations and stipends they offer are either insufficient or have been cut off entirely. Conditions of destitution and near starvation reign. In one camp, Russia has stopped paying rent for the land, so the company that owns the site dumps tons of gravel each day, threatening to force out the refugees, or bury them in their sleep.

Many of the camps’ residents are women whose husbands have been tortured, murdered, or taken to places unknown. The tents these women are given are so meager that some of them choose to take their families to abandoned factories or cowsheds, where they share quarters with livestock. “At Plievo,” Sacco writes, “people hang their food from the ceiling to keep it from the rats.” In one typical story, a woman’s husband was shot and tortured by Russian forces; after he returns, apparently brain-damaged and mute, “he beat [his] own daughter so severely that she also has mental problems.” When not inflicted by the hands of the state, violence appears in families as a kind of hereditary inheritance.

In another scene, Sacco meets an elderly woman who wants to show him a photo of her dead daughter. She can’t find it and soon realizes that her granddaughter (the daughter of the deceased) has concealed it somewhere. “But why do you hide it?” Sacco asks. The girl responds, simply, “Because when she sees it, she cries.”

Sacco’s journalistic skills are rather traditional: he researches, he listens patiently, he reports what he sees, and he doesn’t serve as a stenographer for people in power. By his own account, he doesn’t believe in journalistic objectivity, and his stories are better for it. That is not to say that we are subject to Sacco’s constant editorializing or that his work operates in a radical first-person mode. But the nature of this visual medium makes his presence undeniable, precipitating occasional moments of confession and self-scrutiny. When his interview subjects ask him for help that he can’t provide, he’s aware of his powerlessness. And when he’s embedded with US soldiers in Iraq, Sacco worries, with a Janet Malcolm-like cynicism, that he won’t see enough action to write a story. (The excruciating wait—for conflict, for a bomb to go off, or an ambush to pin down the platoon—ends up forming the crux of the story.)

By Sacco’s definition, a “comics journalist” has all of “the journalist’s standard obligations—to report accurately, to get quotes right, and to check claims.” But there are added requirements, he says:

A writer can breezily describe a convoy of UN vehicles as “a convoy of UN vehicles” and move on to the rest of the story. A comics journalist must draw a convoy of vehicles, and that raises a lot of questions. So, what do these vehicles look like? What do the uniforms of the UN personnel look like? What does the road look like? And what about the surrounding hills?

These choices are reflected in Sacco’s draftsmanship: his figures are vividly drawn, their faces often showing different shades of anxiety, fear, weariness, and melancholy over a half-dozen panels strung together. In the first frame of “Down! Up!”, originally published in Harper’s in 2007, a band of Iraqi National Guard recruits have expressions on their face that tell us immediately these men aren’t cut out for the job.

Sacco largely reports from sites of war, displacement, and military occupation, and certain features recur accordingly—checkpoints and refugee camps; aid agencies confined to the margins; the capricious whims of authoritarian regimes; the militarization of non-military problems; trauma and mental health; people searching for the dignity of work. The seeming monotony in the collection’s emotional register may be a result of the issues he covers—they tend to take on some the same characteristics, regardless of geography or local color.

Even so, Sacco, who, at 51, has been at this for a couple of decades now, seems to have left some veins untapped. He experiments with flashback, offering useful doses of Chechen history or overlaying a survivor’s account of a bomb attack upon an image of the explosion. But his drawings tend to be stringently literal: many panels feature a close-up of a lone figure’s face, dispensing testimony. This is lightened by occasional, improvisatory moments, such as when Sacco’s non-diegetic narration is interrupted, mid-sentence, by a comment from a government official or migrant. The narrative reins are effectively handed off from Sacco to his subject, continuing the story but also producing a frisson of tension. The beams of his comic-book architecture have been exposed. But what more could we learn—about these people, about this still novel medium, about Sacco himself—if he were to tear up the designs altogether?

Jacob Silverman is a contributing editor for the Virginia Quarterly Review and a columnist for Jewcy.